Advancing Artificial Intelligence

With an Artificial Intelligence (AI) class at East, access to AI for East teachers, and increasing advances in this technology, AI has many facets to be explored.

Waking up at 7:00 am, studying Honors Physics at 9:00 am, and finishing AP Chemistry homework at 6:00 pm, East junior Hafsa Raja leads an ordinary highschooler’s life. As any typical student, she is often confronted with the growing use of the world’s latest development: Artificial Intelligence (AI).

“I think I have a pretty basic knowledge on AI,” Raja told Spark. “I use it occasionally. I know that it’s useful for a lot of people, especially when it comes to homework, and even for some teachers.”

Although Raja may not be very comfortable with AI, according to a Spark survey, 62.4% of students at East say they fully understand how AI works, 13.8% say they don’t, and 23.8% are neutral on the topic.

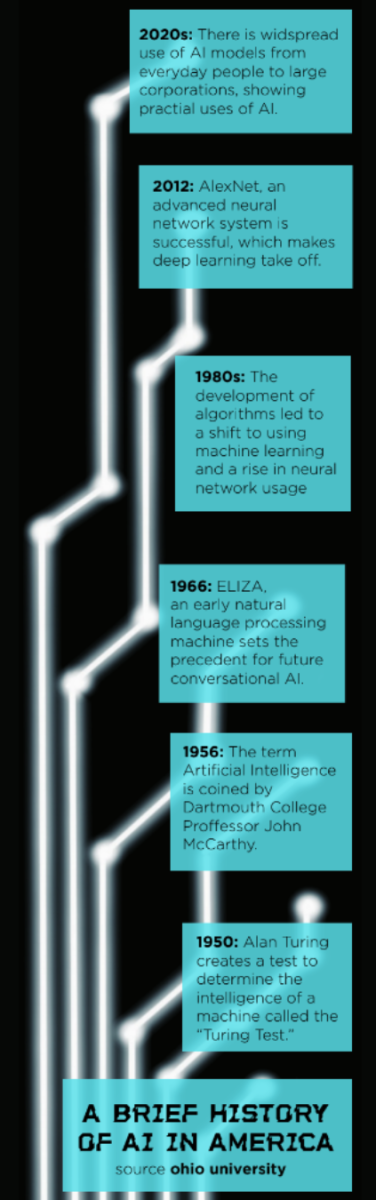

The term “Artificial Intelligence” was coined in 1956 by John McCarthy, an American computer scientist during a seminal conference at Dartmouth College. This event is widely considered the beginning of the AI field.

The discovery that the human brain is an electrical network of neurons inspired many scientists to base their model of AI on the human brain. Mathematician Walter Pitts and neurophysiologist Warren McCulloch conceptualized artificial neurons, which led to the development of the first type of AI, neural networks. Since then, AI has been built on to become what it is known as today.

At East, AI has become accessible for use by educators, and is allowed to be used responsibly by students in the new Introduction to Artificial Intelligence class.

A survey conducted by Pew Research Center (PRC) revealed that 55% of Americans use AI in their day-to-day life. Due to the prevalence of AI, many like Raja are faced with discussions of its applications in the real world, the ethics behind it, and the pros and cons. However, Raja and other students notice that there has been little discussion on how it actually works.

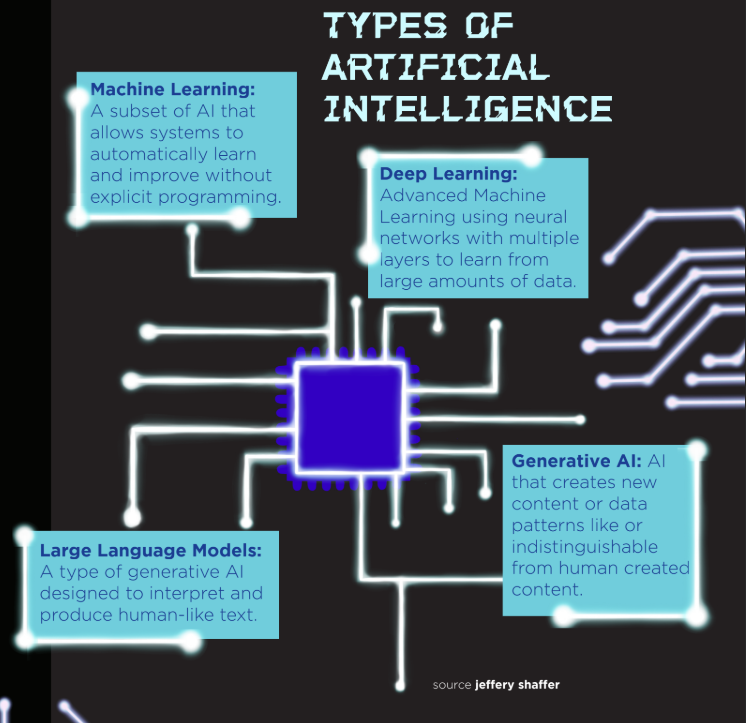

“My simple definition of AI is that you’re trying to mimic human behavior in some way,” Assistant Professor-Educator at the Carl H. Lindner College of Business at the University of Cincinnati and Director of the Applied AI Lab, Jeffery Shaffer told Spark.

He describes AI as a process that is capable of carrying out tasks that historically only a human could do.

According to the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), AI can process large amounts of information more efficiently than a human can.

Machine learning, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), enables programs to perform specific tasks without explicit coding.

To simplify this concept, Shaffer describes teaching a computer to respond to a knock on a door using AI. He does not explicitly tell the computer to say hello when hearing a knock, but rather the computer recognizes the pattern and learns to respond with “hello”.

East junior Gloria Fritsch has taken multiple technology classes like AP Computer Science and Cyber Security, and in them she has learned about machine learning.

“Every time you input anything into a program, it would remember the kind of response you wanted out of it. So, it can get better over time,” Fritsch told Spark.

According to IBM, there are three steps to machine learning: decision process, error function, and model optimization process.

Decision process is when the AI is using algorithms to make a prediction or classification. Based on the data, it will estimate a pattern.

Error function evaluates the prediction made in the decision process. It takes data to compare and evaluate the accuracy of a model.

Last, the model optimization process uses the evaluation of the model to improve the accuracy of the AI model.

AI also recognizes patterns and makes predictions in a process called training according to Shaffer. Training is teaching a computer how to respond by giving it data. The more training data that an AI program is given, the better it can make predictions.

Every type of AI serves a different function, and in order to work to complete a certain goal, they are equipped with different abilities in order to execute their unique tasks. Each type uses machine learning to do these tasks.

Deep learning focuses on AI models that are inspired by the structure of the brain. It consists of artificial neural networks, which can be thought of as a learning algorithm with an input-output relationship. It consists of multiple layers, and the output of one layer is the input for the next layer. Through this process, the data is repeatedly transformed, causing it to have nonlinear features like edges and shapes, which is then combined with the final layer to create a complex object.

“More and more layers with more and more weights and biases connected to it can create a stronger prediction in the output,” Shaffer told Spark. “More accurate [predictions] lets us be able to do things in the output that we wouldn’t have been able to do before.”

One application of neural networks is Generative AI, according to IBM. These are deep learning models that create complex original content. This can be in the form of long texts, high quality images, audios, and realistic videos.

Generative AI is used in programs like ChatGPT which generates text, DALL-E which produces images, and spell check tools like Grammarly.

Natural language processing (NLP) most commonly uses deep learning to understand, interpret, and generate human language. According to IBM, it combines computer based linguistics with machine learning techniques to complete tasks essential for applications like chatbots, language translation, sentiment analysis, and voice recognition.

NLP is one of the most commonly used forms of AI, according to network engineer Jeremy Murray, who uses NLP to help him with his work.

Murray and others see the many benefits that come with using NLP systems, including saving time and money, reducing workloads, and generating revenue.

“Instead of having to do things manually, with AI, it’s really easy to write scripting programs that you can run from one computer,” Murray told Spark.

For each type of AI, there are two ways the program can train with the data.

Supervised learning happens when AI models train on data that is given to them and explicitly labeled. It is called supervised learning due to the fact there is a human overseeing the model as it trains to tell it right from wrong.

If Shaffer wanted an AI model to tell the difference between images of cats and dogs, he would give the model images of both cats and dogs that are labeled. The AI model would learn from the labeled data and would then be able to label pictures of cats and dogs that it hasn’t seen before.

In contrast, unsupervised learning takes place when an AI model uses raw, unlabelled data.

In this case, Shaffer would provide the AI model with a large database of pictures of each animal, and by recognizing patterns, the model could come up with its own concept of a “cat” or “dog” without it being labeled by the programmer as such. It’s considered unsupervised because the answer wasn’t given to the model through labeling during training. In the current world, the only type of AI available is weak AI. These are models that are trained for a specific task rather than having consciousness possessing the general intelligence of a human. When looking at the future, many aim for the creation of strong AI, which is a concept that is only seen in movies, such as “WALL-E” and “Her.” These systems have the ability to comprehend, learn, and apply. They have the mental capability and intelligence of a human. They are self-aware and can understand and reflect on their existence.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), a hypothetical form of strong AI, surpasses human capabilities across a multitude tasks.

“AGI is this idea where it’s a type of AI that is capable of doing things better than people are in terms of cognition,” AI specialist and data scientist, Aedhan Cornish Scott told Spark.

AI models are expected to grow increasingly at a rapid rate. As this happens, AI systems are expected to improve industries such as healthcare, customer service, manufacturing, and more.

Examples of this growth can be shown in the healthcare field specifically.

“[AI] is offering numerous applications that enhance efficiency, improve patient outcomes, and even streamline many administrative tasks,” business professor at Lindner College of Business at the University of Cincinnati, Dr. Dong Gil Ko told Spark.

There are four main ways AI is being incorporated into healthcare: medical imaging and diagnostics, disease predictions, drug discovery, and health records.

AI systems can assist with medical imaging and diagnostics by analyzing images that would take a human much longer to complete.

“[AI models] are able to detect abnormalities like tumors, fractures, blood clots, and things like that,” said Ko.

They do so through algorithms developed in which the AI models use pattern recognition to see, based on given information, what they can detect.

AI systems also help with disease predictions. The AI models are developed to analyze a patient’s data and predict different conditions, like diabetes and heart disease. This allows physicians to diagnose and intervene earlier, increasing patients’ probability of an easier recovery.

Another big area in which AI is used in healthcare is in drug discovery and personalized medicine.

“AI actually accelerates drug discoveries,” said Ko. “You can imagine pharmaceutical companies being all over this.”

The AI models are able to analyze data, including chemical compounds, biological pathways, and diseases, to determine multiple drug candidates.

The last area deals with NLP systems being used to help with electronic health records. This is a database of all of the information about every patient’s vitals, medical history, and the biggest area: clinical documentation.

“AI-powered NLP tools can extract key information and electronic health records, be able to efficiently sum nodes, and quickly bring in integrated lab results and other data,” Ko said.

Machine Engineer Kevin Sobkowiak describes how he thinks AI will impact his career by saying it will be “incorporated to make the work we do more efficient.”

Sobkowiak’s job involves researching information which can get difficult when it is not all in one place and may be difficult to interpret. AI systems can help in that process by looking for common patterns among data for successful and failed methods tried in the past. AI models are not only being incorporated into technological fields; AI is directly impacting everyday people.

A study done by PRC shows that more than half of Americans are more fearful than excited by the increased use of AI.

Regardless of a common fear for the unknown, Raja said she knows that having general knowledge about this relevant topic will instill her with the abilities needed to develop a progressive society and have confidence rather than concern for the future.

A variety of high school and college educators share their experiences with AI being implemented into academics.

In the beginning of every school year, East Speech and English teacher Dave Honhart has his students handwrite a promise not to use Artificial Intelligence (AI) in their writing. His view of AI is that it is not acceptable for students to use it in the school setting for writing; however, from the inside of East to across the country, people involved in education have many different opinions on how AI should be implemented in academics.

With how quickly AI changes and grows, learning about it is the first step to being fluent in the world of technology. AI literacy is what drives the advancement of this technology forward, and AI in the workplace starts with AI literacy in school. No matter how AI will change in the future, humans are ultimately the ones who are driving that change. Many high school students are learning how to use AI on their own, some high schools are teaching students how to ethically use AI, and other schools are not prioritizing AI literacy for students.

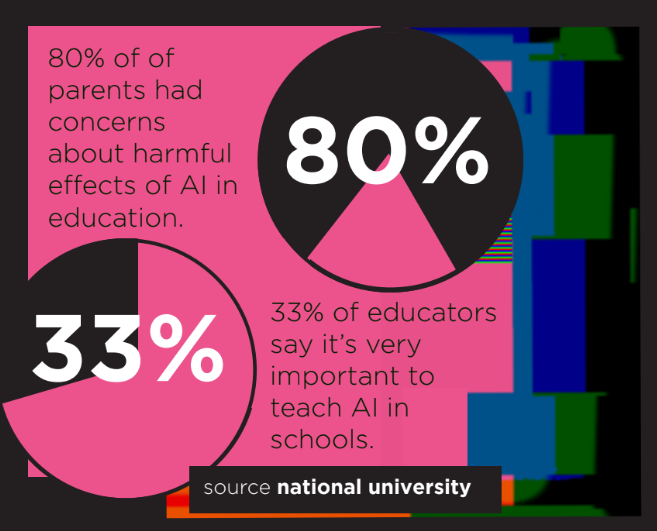

Students can learn the basics about the ethics and applications of AI in a new class offered at East called Introduction to Artificial Intelligence, which is also offered at West. Lakota Director of Curriculum and Instruction Andrew Wheatley said that this class is in the Social Studies department, and it is a one-semester starter course that will give students general information about AI. He said that this class has been introduced to Lakota as a response to how prominent AI is in current society and the potential impact it could have in the future.

“This class allows us a place to start quickly, learn, see what works and doesn’t, and then scale out AI education to all,” Wheatley told Spark. “Considering how new this technology is, and how quickly it was thrust into our everyday lives, I believe it is critical to understand the impact that it is having on all of us.”

Wheatley said that, even though there are many positives, he also sees the negative effects of AI in education. While students can “chat” with AI, it lacks the human connection that students need in order to form social skills. According to Stanford Medicine, social connection leads to a 50% increase in longevity and strengthens the immune system. It also leads to lower rates of anxiety and depression and faster disease recovery.

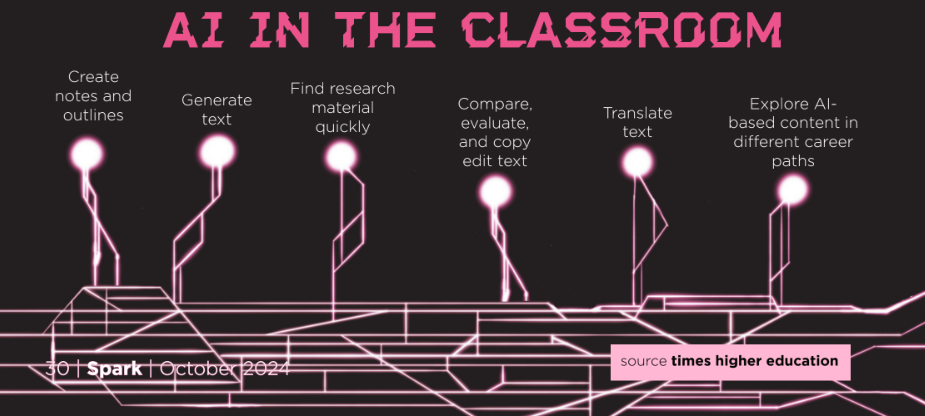

East Introduction to Artificial Intelligence teacher, Joe Murray, said that AI can be used in a number of ways by both students and teachers, and that he has seen the effect of AI on a broader spectrum than just in the class he teaches. One way that Murray said AI can be used is as a sounding board, to bounce off ideas from. He said that it is very easy to get fast and clear feedback from AI.

Murray also has used AI to translate notes for students whose first language is not English by creating a slideshow using AI, and then generating that same slideshow in another language. Or, if a teacher needs the same slideshow for an honors versus a CP class, AI can create one slideshow that is more detailed than the other. This usage of AI isn’t just in Lakota. In a Forbes survey of 500 educators from across the US, 60% reported that they have used AI to improve their teaching materials.

One of the more major concerns for Murray and other teachers is the fact that access to AI could lead to larger class sizes. If teachers can use AI to more efficiently make lesson plans and teach a larger group of students, then class sizes could inevitably grow to be so large that teachers are unable to connect with individual students. According to the Pew Research Center (PRC), “A quarter of public K-12 teachers say using AI tools in K-12 education does more harm than good. About a third (32%) say there is about an equal mix of benefit and harm, while only 6% say it does more good than harm. Another 35% say they aren’t sure.”

In Murray’s classroom, they use AI because of the curriculum, but that does not pass in every class. He explained that there is no specifically drawn line for how much AI could ethically be used by students. In most cases, using AI to write an entire research paper would be considered plagiarism and therefore not original work. However, the line gets a little blurrier when a student uses AI to create an outline for a paper, but then writes the rest. Even further, if a student uses AI to find all the resources and do all of their research, then is that ethical? This line is drawn in different places depending on different peoples’ ethics and priorities.

In Honhart’s classroom, he has also seen these negative impacts of AI for students. He said that English classes are one of the most affected by the rise of AI, especially in essay writing. In the same Forbes study, 65% of those 500 educators said that plagiarism is the main concern of AI being in education, and 64% of them said that AI essay generators were the main feature that students use the AI for.

Honhart said that, while AI catchers such as Turnitin are frequently used by English teachers to ensure that essays are written independently from AI, there are also other ways to make sure students are submitting their own work. For example, he has assigned more writing on paper rather than online so that students do not have access to AI.

Honhart said that people often compare using AI as a tool for writing to using a calculator for math. He said this is not a fair comparison because, for a calculator, you still need to have some sort of knowledge of math to work it. Instead, Honhart suggested that spell check features would be a better comparison to a calculator. Regardless, rather than coming up with their own ideas and outlines, some students immediately jump to AI as a crutch.

“I’ve heard the argument that AI can help [writers] organize their thoughts and build an outline. That’s still part of the writing process,” said Honhart. “That’s every bit as important as the actual construction of the sentences and the building of the paragraphs. It is something that we as teachers need to figure out a way to make sure that students are still developing as writers in the manner that they should.”

Assistant Professor-Educator at the University of Cincinnati in the Carl H. Lindner College of Business and Director of the Applied AI Lab, Jeffery Shaffer said that AI can sometimes be used as a copy editor, which is a better use of AI than using it to write the entire essay. He believes that humans and AI working together is where the best products come from.

“If you give the power back to [generative] AI and say, ‘Here’s my first draft’ and then I’m going to make some edits. I’m then going to pass it back and say, now be a copy editor,” Shaffer told Spark. “What if I apply my critical thinking to this technology, rather than just let the technology go off and do its thing? That’s where I think you get a really, really good product.”

Wheatley also said that AI gives students a new, easier avenue to cheat. In a Spark survey of 332 sophomore, junior, and senior East students, 49.4% responded that they had seen someone use AI for their school work, while 49.4% responded that they had not. 1.2% did not answer. Wheatley said that, while the amount of cheating may not have increased, AI creates new, easier ways for students to cheat, and the students who did not cheat before are more likely to cheat now. Honhart said that the fact that AI is accessible to students makes it even harder for teachers to ensure academic honesty.

“It’s not good screwing up in high school, but it’s better here than in college or in the workplace,” said Honhart. “I think most students are going to do things the right way, and it is up to us to read what they write and make sure it’s their work.”

Air Force Institute of Technology Associate Data Science professor Bruce Cox is also very close to the action in how AI is growing and developing in college. Cox teaches Department of Defense (DOD) students, including many Air Force and Army students who will be working in DOD jobs such as aircraft testing, flying aircraft, IT, human resources, and much more. When these students transition to the workplace, they likely will use AI in some form.

According to Cox, it is hard to find a profession where AI is not present. In many jobs, AI is taking over the tasks that are not safe for humans to perform or those that are repetitive, boring or uncomfortable.

“Other ways I’m seeing AI affect the workplace in manufacturing is developing materials and developing new types of medicines, new antibiotics, new gene treatments,” said Cox. “A lot of the biomedical industry is utilizing AI to assist them in their research. So, a lot of the new drugs and a lot of new developments you’re seeing in biomedical fields are being assisted with AI. It’s almost hard to say where it’s not playing a part in the workplace.”

The students in his class also use the same AI large language models that students at high schools often have access to. All of Cox’s students have a subscription to Chat GPT or another AI program, and they use it to help them write research paper drafts, as a personal tutor, and for research or coding help.

A national educational company called AI for Education aims to provide AI literacy for 1 million educators by furthering the knowledge that schools have about the different AI tools that they can use. They have already reached around 150,000 educators, and they do so by hosting webinars, virtual trainings, in-person trainings at schools, and free online courses. They work primarily with teachers, but also with school leaders like superintendents, and occasionally with students themselves. Mandy DePriest, the content and curriculum developer at AI for Education has been with the company for almost a year.

“We feel like AI literacy is the foundation of all informed decision making going forward,” DePriest told Spark. “We’re not here to say AI is amazing. We’re here to tell you what you can do with it, and then let teachers and schools and districts decide what they want to do with that knowledge. We try to be balanced and neutral in our approach.”

She has seen a variety of ways that different schools approach AI. Some schools are advancing alongside AI and implementing it into their policy, while some schools are more hesitant. However, DePriest said that while it may not be easy, keeping up with AI is necessary for students because of how influential it is and will be to society as a whole. In the Spark student survey, 43.4% of students agreed that AI is easy to use, while 31.9% strongly agreed. Compared to the 4.2% of students who disagreed and 0.6% of students that strongly disagreed, the strong majority of students believe AI to be easy to use. 19.6% of students were neutral on the topic.

“Truthfully, this technology is showing no sign of stopping anytime soon,” said DePriest. “So, you run the risk of usage going unguided and things becoming the Wild West. What we recommend is an approach called guided use, where districts identify what tools and what uses of AI are appropriate, and then make them available to students clearly.”

East Principal Rob Burnside said that East is choosing to evolve alongside the technological world because these AI technologies that students use in high school are very similar, if not the same, to what students are going to be using in college and the workplace. In a survey by the PRC, 32% of US workers say that they are not worried about AI taking over their jobs. The willingness at Lakota to teach the AI class stems from the idea of keeping up with tech innovations and teaching modern material to students.

“We could say you’re not allowed to use AI in any way, shape, or form, but you’re going to live in a world where it’s only going to increase in its prominence,” Burnside told Spark. “We’re preparing you for the future that you need.”

Lakota’s Board policy 7540.03 states that AI and Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools should not be used by students to complete their school work because it is considered plagiarism. However, students may use AI/NLP tools in the event that their teacher has given permission and it is used for research assistance, data analysis, language translation, writing assistance for grammar and spelling corrections, or for accessibility for students with disabilities.

In a meeting with Lakota teachers, Wheatley provided information on how AI would be implemented at the district. Teachers were encouraged to use AI as a way to assist and improve their teaching resources. He also touched on the importance of fact-checking AI because the accuracy of information taken from AI can sometimes be wrong.

Wheatley also touched on the fact that AI has a much broader scope than just programs like Chat GPT. AI is constantly changing, and it has already been integrated into many workplaces. The future of AI might look very different from how it does now, but the general trend of AI improvement continues. According to National University, 77% of companies are currently using or implementing AI into their workplace, and 83% of companies view AI as a top priority in business plans. This amount of AI in the workplace has come a long way from AI in the 1950s. Throughout the years, AI has continued to be implemented into the daily lives of people. More and more people are learning alongside generative AI to be able to use it to humanity’s advantage.

According to DePriest, whatever the future ends up looking like, AI will be a major part of it. In order to keep up with the advances, people are educating themselves about AI, and that starts in schools. She said she would love to see a future where education is more in the students’ hands due to their access to AI, allowing for more specialized learning that students could direct on their own. It could make education look very different, but DePriest said that these changes in education must follow the way that technology is already moving, and it is essential for students to be able to function in the workplace.

“I would like to see AI transform into more student-driven instruction,” said DePriest. “That way, we could really emphasize 21st century skills like critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and all these soft skills that you’re going to need going into the future.”

Cox said that the future of AI could be anything that humans want it to be. From increased large language models on cell phones to clothing that takes health vitals, AI will continue to improve just like any other technology.

“I think the pessimists will say that AI is going to take over the world and lead to the downfall of humanity. Optimists would say that AI is going to lead to a brighter future, and the reality is probably something in the middle,” said Cox. “I think that we’re going to see AI become integrated into everything we do.”

A new Introduction to Artificial Intelligence class at East takes the first step toward preparing students for the rapidly evolving impacts of AI and encouraging them to think critically about how AI affects their everyday lives.

Users of Instagram, TikTok, Youtube, or any other scrolling app of their choice, sift through millions of posts everyday, allowing themselves a moment to turn off their brain. Suddenly, a clicker ad breaks one user’s chain and encourages him to take an attempt at winning the lottery. Annoyed, he scrolls past the ad assuming it’s generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI). What he did not realize was that the photo of that moose in the forest and an abstract art piece seven posts ago was also AI-generated.

Newly introduced in the 2024-2025 school year, juniors and seniors at Lakota can now take the class Introduction to Artificial Intelligence. The class is currently available during fifth period and is the first class at Lakota specifically dedicated to the study of AI. The class covers topics such as the history of AI, how and why it works, and especially the ethics of AI. Currently, the only AI program authorized for use in the class is called Microsoft Copilot.

Intro to AI teacher Joe Murray encourages those unfamiliar or unsure about how AI works to explore those concepts in this class.

“This class is the first exposure [to AI] for some people,” Murray told Spark. “It’s very introductory. So if you’ve never even heard of AI before or have any kind of background on it whatsoever, take this class. It’ll introduce you to not only what the history of it is, how it works a little bit, but you’ll actually get to put your hands on it and play with it a little bit.”

AI touches just about everything in the world today. According to Murray, even mundane tasks such as note-taking can be simplified by “AI taking all the notes for them and condensing a meeting down into a couple of key phrases.”

East Junior Alyssa Hall appreciates the information the new class provides and how much awareness it offers for students about the different aspects of AI.

“The basic info is good to have,” Hall told Spark. “It keeps you informed with knowing how things work.”

The ethical perspectives of AI are a major focus of the class. Class discussions and debates about when, why, and how AI should be used in different settings, such as school or work, is one aspect of the class where students examine both the helps and hindrances of AI usage.

“AI is constantly advancing at such a fast rate,” said Hall. “And we don’t even realize it. You can use it for social media or even advocating for certain communities.”

Not everyone is on board with the increased use and importance of AI in the contemporary world. East Senior Aaron Gideon uses the class to remain vigilant about the ramifications of increased AI use.

“I’m not a big fan of AI because it can cause a lot of vulnerabilities,” Gideon told Spark. “AI works by taking data and applying it. It’s called machine learning. I wouldn’t use [AI] because of the fact it stores so much information.”

As AI constantly changes, adapts, and improves in creating realistic ideas and products, expanding the educational opportunities to gain experience with AI programs and analyzing its real-world effects is becoming a greater conversation among educators than it has been in years past.

“I think that the class should be expanded upon in the future,” said Gideon. “I think more people should be made aware of [AI]. If I were to say ‘I take Intro to AI,’ people would be like ‘What, we have that class?’ Most people don’t really know what AI is. They just hear about it. It’d be pretty good for people to know about what it is and what it could mean for us.”

ArtificiaI Intelligence models are used to track and improve social media content involvement, impressions, and activity. The use of this tool in social media will only increase as more people discover how to use it.

Stephen Hawking said that “computers will overtake humans with AI within the next 100 years. When that happens, we need to make sure the computers have goals aligned with ours.” While technology has not reached that point just yet, advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) are moving at a fast rate.

According to Inside Higher Ed, 40% of students across the globe use AI, and AI has a huge influence on many teens.

From a Spark survey of 332 East students ranging from sophomores to seniors, 56.9% responded that they checked social media multiple times a day, 28% said they check it a few times a day, 3.3% said they check it once a day, and 9.6% said they rarely ever check social media platforms.

Social media has become a significant part of the teenage lifestyle according to Pew Research Center (PRC). A study done by the PRC in 2022 revealed that more than half of teens say that it would be difficult for them to give up social media.

“I like that I can text people [on Snapchat] without having their number, I can send snaps to my friends and share moments that I would want to share but maybe not post on Instagram,” East senior Brynn Sellers told Spark.

Snapchat was founded in 2011 and has evolved through added features such as lenses and ads. As of February 27, “My AI,” a generative AI chatbot, was also added as a new element according to The Standard. The chatbot utilizes the same technology that ChatGPT uses and was added to Snapchat for the purpose of “offering recommendations, answering questions ,and converse with users,” as released by CNN.

“I think [My AI] can be good at times but I also think it can be really, really bad at times,” said Sellers. “If I’m unsure about a question, I’ll double check my answer using [My AI].”

16.5% of students from the Spark survey answered that AI is prevalent in their lives, 30.1% were neutral, and 53.3% either disagreed or did not answer the question.

There is no question that AI is present in many aspects of the world today. Basil Mazri Zada is an Instructional Faculty in Digital Art and Technology for Ohio University and has pioneered the use of AI to benefit the curriculum.

“I teach in the Digital Art and Technology Program, and it’s a new program as part of the Bachelors of Fine Art,” Mazri Zada told Spark. “I started to adapt AI in relation to our curriculum to allow students to explore what it is rather than having a full rejection of it, because AI is rising really fast. Each semester, students are more reluctant to use it, but at the same time, my idea is, you need to understand how it works, how it generates, and how you could protect your future career by trying to understand it and adapt to how to create original work with it, rather than fully rejecting or questioning it.”

As a rule of thumb, Mazri Zada instructs his students to be wary of what they put into AI platforms and what they post on their social media, out of caution when it comes to AI possibly using their work to train on.

AI is present in social media in many different ways. According to Marketing AI Institute, some ways that people use AI in social media are to uncover deep insights about the platform’s audience, formulate posts and content automatically, discover trends to understand consumer needs, and predict which type of content will receive the most reactions and clicks.

“To me, it looks like social media companies use AI for the visual aspect of advertisement,” said East senior Mason Viox. “It makes me wonder how many missed opportunities that AI has taken away from smaller profile graphic designers.”

Associate professor of Communications Design at Miami University in the Department of Art Dennis Chetham is an expert in detecting what is created with AI as well as the ethicality of AI generated art.

“ChatGPT is a really common [generative AI platform] that’s text based, but it’s actually more multimodal, as it’s hooked into DALL-E (a visual based generative AI). Then, there’s Mid Journey and other tools that are a little bit more focused on images, and on video outputs like that, but they’re all creating content,” Chetham told Spark.

The content that AI models produce is not only art, but any content that can be generated for creators to use. From a Spark survey, 74.8% of students said that they believed AI is used in social media, 10.6% said they were not sure, 2.7% said there was no AI use in social media, and 11.8% did not answer.

Of the 332 students surveyed, 77 of them believed that AI algorithms make social media more engaging.

“One of the things about how social media used to work was you saw content because people put out content to you, and now we live in a world where you see content because of the algorithm,” said Advocate for Tech Accountability and Transparency, Frances Haugen. “Once that happens, you have to ask a lot of questions, because now you’re better be able to trust that AI. Any biases are going to influence your perception of reality.”

Another concern that AI is presenting is faking the voices and personalities of humans.

“AI is trained right now to be able to regenerate images and sounds based on real people,” said Mazri Zada. “Right now, there is AI that, based on 20 images on social media, will be able to train a small database that could start generating images of the person’s likeness on any image possible.”

Mazri Zada is describing what are known as deep fakes, which are some of the recent concerns that all result from AI.

“We’re seeing the beginnings of this now, but [AI] is getting more and more sophisticated very quickly, creating fake audio and creating fake images, fake video, even just from prompting alone,” attorney and shareholder with Ennis Britton Co., L.P.A. Ryan LaFlamme told Spark.

VEED.IO, Eleven Labs, Speechify, and Well Said Labs are only a few of the many websites that utilize AI in order to mimic a person’s voice. VEED.IO’s website states, “VEED is the most efficient and powerful tool you can use to mimic your voice with AI. It’s fast and only takes one recording for our Artificial Intelligence software to create a customized voice profile.”

Platforms like these may cause confusion over what is real and what is not.

“I think in the future, there could be some issues, in some cases where there are serious concerns about the authenticity of evidence,” said LaFlamme. “Is this video that we’re seeing real? Did this person really do this?”

LaFlamme also believes that this issue will not be going away, but instead it is going to grow exponentially.

“I think we’re going to see people using the excuse that things are AI, and that’s going to shift burdens to people about who has to prove this now.”

Not only is faking of evidence a concern that AI raises, but the faking of detecting whether something was AI generated and whether those are false positives is also a topic within itself.

“I know that some of these programs that try to analyze get false positives all the time, and so that’s a whole other sort of aspect of this. Even disproving AI could be difficult too,” said LaFlamme.

Along with proving whether or not AI is real, both LaFlamme and Mazri Zada emphasize the need for new laws to be made in order for humans to know what is AI and what is not. Misinformation and polarization in the world of politics right now is a conversation that is evident on social media platforms such as X, Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat.

In 2020, Vox published an article titled “How Social Justice Slideshows Took Over Instagram”. The article analyzes the “bite size squares of information” that could be considered “something like PowerPointactivism”.

The slides presented information ranging from defunding police to mail-in voting. As found by Statista, the average monthly Instagram users increased from 500 million to 2000 million between 2013 to 2021. User Generated Content (UGC) was at an all time high and whether or not the facts being posted were true was a massive concern for users.

“Even interference in elections by having AI sound like certain candidates and trying to create public misinformation without going into who is doing what, is problematic,” said Mazri Zada.

According to Mazri Zada, the issue is more than just deep fakes.

“It’s anything that AI could be abused to affect public opinion about a lot of things, including fake news, causing public outrage,” said Mazri Zada. “Even in newspapers, if they spread a mistake and then they own it in the next issue, the amount of people that will see the correction is really small.”

Artists, intellectuals, and lawyers engage in legal and ethical discussions around whether art generated partially or fully by Artificial Intelligence can be considered another medium for artistic expression, or if using it takes the “humanity” out of the humanities.

Each touch of her paint to the canvas is intentional. Each line that follows the path of her brush as she layers paint on top of paint has a meaning. Each color choice adds to her unique vision.

East senior, AP Art History, and AP Art student Grace Allan has a plan for everything that goes into her artwork.

“I feel like [art is] about the intent and it’s about the person who made it, so I feel like the AI business is just a computer being told what to do, and it has to do it,” Allan told Spark. “It just steals from other things that it knows of, but it doesn’t make an original, full, thought-out piece.”

At Lakota, teachers have been instructed on a Generative AI program called Microsoft Copilot that is available for teachers on their district online portal, OneLogin.

East AP Art History teacher Dani Garner uses AI to help her develop rubrics for her classes, and said that it is “mind-blowing” how much more efficient she is now than she was before beginning to use AI.

“As a teacher, realizing how busy I am, I’ve been using it more to help me, and it’s actually incredible. It’s not ‘cheating’ the way I’m using it,” Garner told Spark. “I think at this point in time, it’s work smarter, not harder. If there are tools for anybody, why not use them?”

Other high school art teachers also consider on uses for AI in relation to what students are doing for their assignments.

“[Some students may] struggle with coming up with more, or coming up with iterations of an idea. I think AI would just be thought provoking,” AP Art teacher Joseph Walsh told Spark. “I think in some ways it would be kind of sad, because I feel like [brainstorming ideas] would naturally have happened in group conversation and now, instead of talking through ideas with people, it would be going to AI as another person.”

Walsh, and other art teachers and professors recognize the efficiency and speed of AI in this aspect, regardless of the lack of human interaction. According to Walsh, AI gets rid of disagreement between people because, “AI is very polite.”

Similarly, in a time crunch or when in need of a neutral party, AI can be useful, but it shouldn’t take away from artists’ original thought according to Garner.

“You want people to be creative, and you don’t want people thinking for you in a creative way. It’s one thing for [AI] to help you, but creativity should come from within,” said Garner.

At various universities in Ohio, the implementation of AI into graphic design classes have highlighted some of this discourse.

“AI can do mundane tasks, like if I’ve got a subject [in a photo] and I need to remove them from the background so I can use them somewhere else. AI can mask out (separate from the background) their hair and create a very believable masking,” Associate Professor of Communication Design at Miami University Dennis Cheatham told Spark.

AI is able to do tedious and repetitive tasks which saves time for not only those in the creative fields, but also anyone who can benefit from AI generating code, spell checking text, or translating between languages.

“Talk about saving 12 to 20 hours of time,” said Cheatham. “The benefit there is that, instead of masking out hair, I can actually focus on the real creativity, such as developing a logo or coming up with a strategy, or testing an app.”

According to Cheatham, AI is also used in commonplace platforms like Adobe Photoshop to cut out an object and move it to a different background, but also to generate parts of images in order to modify a photo.

It is possible to generate parts of, or even whole images or artworks for free online with other platforms also, such as DAE, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion.

This may create confusion about what parts of a final piece of artwork were done with AI, or whether or not an artwork was done completely by AI from classroom environments to occupational ones.

According to Walsh, the use of AI on any aspect of the completed artwork submitted for the AP Art exam is prohibited because it becomes difficult to tell what part the student did, and what the AI generator did, making it difficult to grade.

Professional artists like Associate Professor of Media Communications & Technology at the University of Cincinnati Blue Ash College Nicole Trimble, also worry about the usage of AI involving the integrity of their occupation.

“Easier is not always better, and I fear that an over-reliance on AI may make us lazier in regard to mastering our craft,” Trimble told Spark. “To be a successful artist, you need to be able to translate what’s in your head to your medium of choice. If you never learn to master the skills to do that, you’ll be stuck relying on other’s work instead of your own skills and creativity.”

While the usage of AI as a tool for generating ideas or for parts of artwork may seem low-effort to some, Cheatham sees prompting AI as valuable work itself.

“Using one of these tools, you have to write very well-considered prompts. You have to really consider what words you put in, and that requires a great deal of critical thinking and logic,” said Cheatham. “That is a really good skill, and teaching how to articulate what we want, how to communicate effectively, has always been a goal of education for as long as we’ve had formalized education. These tools are one more way to have to practice writing and communicating effectively to one of these systems.”

According to Ohio University Instructional Faculty in Digital Art and Technology Basil Mazri Zada, for these prompts to generate anything, AI must have a database to pull from to train and synthesize into what is known as AI-generated art.

“Artists worry about AI being trained on the likeness of their works without them being compensated,” Mazri Zada told Spark. “Artists are worried that, in time, [AI] will steal their work and then produce something that looks like their work, while they are not being compensated or agreeing to that [usage].”

Most states have laws relating to different aspects of AI, and there are various interpretations of the law when it comes to cases revolving around AI, although there are no federal or Ohio state laws that address AI directly as of October 2024.

Justices at each level of the court system in the US are constantly interpreting the constitution and setting laws when it comes to the legality of where AI generators source their content from, as well as who then owns the copyright to the final product.

“AI trains on internet-sourced material in a lot of cases, and by doing that, it is basically incorporating copyrighted works into its training modules,” attorney and shareholder with Ennis Britton Co., L.P.A. Ryan LaFlamme told Spark. “Not just copyrighted works, but also trademarks, service marks, logos, and things like that. There have been some pieces of litigation so far about training models in the content that goes into who owns the rights of the [AI generated] content.”

The person who gives the AI model instructions to generate a piece of art or writing may have some claim to ownership of the prompt and what it creates from that because of the importance of prompting to the function of the content creation, according to LaFlamme.

While definitive legal stances on AI have yet to be widespread across the US, in the district court case Thaler v. Perlmutter, the plaintiff owned a computer system that he claimed generated a piece of visual art, and argued that the copyright for the work should go to him, but was denied by the Copyright Office on the grounds that the work was done without human involvement.

The court ruled with Perlmutter from the Copyright Office that the copyright for the AI- generated art should not go to the person that used the machine to create the work because the image lacked human involvement in its creation.

However, this does not address the ownership of art that is partially generated by AI.

“There is still no clear law of who owns AI work, so based on a couple of interpretations of a copyright law, AI work currently in its basic form falls under public domain,” said Mazri Zada. “Instead of [an individual owning it] if you could prove your intellectual contribution and effort [to the AI work].”

Technology is known to move faster than the law can attempt to regulate it according to LaFlamme.

“I’ve been doing this for 17 years now, the law has always been behind technology, and I think it always will be. We don’t always know the immediate consequences of technology,” said LaFlamme. “They are not young programmer types in those general assemblies. So, [lawmakers] may not even understand the importance of some of this stuff. For that reason alone, there are practical reasons why the law is always behind technology, and I think with AI in particular, that is going to be a very large gap for a while.”

As of now, US courts continue to address cases surrounding AI by interpreting older copyright and defamation laws, although LaFlamme predicts that there will be cases that lead to the creation of laws focused on AI specifically.

Outside of legality concerns over the process of creating and declaring ownership over creative work generated with AI, artists like Trimble and Allan may consider whether AI generated art can be classified as “real art.”

“Art is an expression of emotion and engages our higher faculties, like imagination and abstraction,” said Trimble. “Very importantly, art doesn’t fill any of our basic needs, and yet we are motivated to create it and seek it out to experience it, with no other compensation or reward than the experience itself, which is uniquely human.”

While AI may be able to recognize patterns and predict the consequences of an action on a person’s feelings, AI itself does not have the capacity to feel or express emotion in the way that humans do, according to Shaffer.

“Can [AI] show me an image that I’m moved by? Absolutely, but some human being prompted that. They wrote the description to get that image. So, to me, there’s still some kind of human element in there,” said Shaffer. “Could [AI] write a story that could make you cry? Probably, but somebody prompted that story. Somebody tried to get that story out of the machine. We might be able to emulate [emotion] in some way [with AI], but I don’t think we’ll have to worry for a while about [AI] having emotions.”

Attempting to get AI to understand human emotion and convey that through words or pictures is a compelling idea to Mazri Zada.

“I work with AI to explore how AI views memory, nostalgia, and trauma because, as a human, we view trauma differently than how a computer that has never experienced trauma tries to view it,” said Mazri Zada. “I have two artworks right now, in two different exhibits, that are about how AI responds to our concept of destruction using language and images from previous artworks that I did about destruction and war, and how AI reimagined that based on their training.”

Mazri Zada looks to show the intellectual difference between how humans and generative AI express emotion through art by asking the AI model to generate art that shows destruction or trauma. Without saying the word “war” to the AI model, it comes up with images of war because it recognizes that as something humans associate with the destruction and trauma through pattern recognition.

According to a Spark student survey, 67.1% of 332 East students ranging from sophomores to seniors believe that AI is not “real art”, with 10.8% saying it is “real art”, and 22.1% being unsure or unwilling to answer.

“AI art is created by compiling human-made art together, so it’s not that it isn’t art, it’s more that it’s a subcategory of art that’s imitating art made by humans,” said Trimble. “We can be entertained by and even inspired by it, so it’s doing the same thing a human-made piece would be in that regard, but it must be acknowledged that it is AI art, and when we describe something as art, the understanding is that it is made by a human, and everything that entails.”

According to Shaffer and many other experts, AI is not going away any time soon.

“Pandora is out of the box. I don’t think we have a choice. As a society, we are going to have to deal with [AI],” said Shaffer.

This is a call to action to AI experts and artists alike according to Mazri Zada, who champions using AI as a tool rather than a crutch to his students.

“AI is here to stay. Learn how it works, how to protect [artists’] work, and how to use it as a tool. Don’t stop using AI, [instead] learn how to use it ethically, use it to increase productivity, and create original work,” said Mazri Zada. “It will get regulated, but we have to make sure we are ahead of the curve in learning how to be able to adapt and work [with AI] and be creative minds.”

While AI can generate “art,” Cheatham does not believe that AI will replace human artists because of their lack of being able to experience emotion, which can be the basis of artistic expression. “While these tools can create some pretty striking imagery, they don’t yet understand that imagery communicates the human condition or what can capture some of the challenges that people face that art grapples with,” said Cheatham. “I think there will always be a need for us to know that [a piece of art was created by] someone like us, another person, as part of their expression, and their experience, and their story. Art is about telling us about an artist, telling their story and reflecting ourselves as a society back to us.”

For Allan, as an artist, creating is about more than a future career that she fears may be usurped by AI as a technology. Intrinsically intentional, Allan naturally places paint on her canvas, creates lines, and chooses colors. Most importantly, she said, is that art is not just about the final product, but also the process of doing it.

“Some art is less of [an expression of] emotion. Some people do abstract art just for the fun of it, or the act of it,” said Allan. “Even with a kid with a coloring book, their intent is to do something for themselves. It is very therapeutic and that in and of itself is very human and very artsy.”

As Shaffer views it, it is important to adapt to a future with AI, even in the humanities.

“We’re problem solvers. We’re critical thinkers. We have emotions. We have artistic ability,” said Shaffer. “AI doesn’t have any of that, and that is what we bring to the table. It should be our humanity that we bring to the AI.”

Professionals ranging from economists to artists discuss their premonitions of how AI will impact the occupational world.

As any new technology does, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has taken the world by storm, putting into question what many people’s concerns revolve around: the economy.

According to James Pethokoukis, an economic policy analyst and the Dewitt Wallace Chair at American Enterprise Institute, as of now, AI is a generally good thing for the economy.

“If we prepare workers with the right skills and create smart policies, AI can lift everyone up, create more opportunities, and help the economy thrive for all, just as previous innovations have done,” Pethokoukis told Spark.

He and others have seen the benefits AI can bring to fields from medicine to agriculture.

“AI in agriculture is already helping workers increase crop yields by analyzing data to make better decisions on watering and planting, which could lead to more food at a lower cost.”

Even though AI may seem like a big economic help now, tensions are rising for people in the arts.

Richard Castle, a videographer at R&L Carriers, said AI has impacted his job substantially.

“[AI] has impacted my career positively; there have been no negative consequences from it. No one has lost their job, and it has only helped us,” Castle told Spark. “Has it caused fear among my peers? Yes. Has it caused controversy? Yes, mostly on the integrity of the work, especially when it comes to art.”

The fear of AI taking artists’ jobs is common where Castle works.

“AI is quickly showing shortcuts and it’s threatening those [artists, graphics designers, and animators] and they have a right to feel threatened by it because that’s their livelihood, that’s what they specialize in,” Castle added. “A lot of artists don’t really work for a company. They have clients and they’re soon going to lose their clients which requires them to search for more work and that takes time away from actually performing at what they’re good at.”

Castle and others believe there is a way to prevent AI from negatively impacting careers, artistic and otherwise.

“It’s almost unavoidable, the only ways to do it are having regulations, companies making ethical choices on what kind of work they want to use, and letting people know that [the AI art] was created by a machine, not a human,” said Castle.

Basil Mazri Zada, Instructional Faculty in Digital Art and Technology at Ohio University recommends that artists and designers bring their work to life to prove their value against AI generated art.

“[Artists] need to show their worth, of why [people should] pay someone who is an intellectual, who knows how to reflect my visual identity, reflect my product, and reflect my ideas,” Mazri Zada told Spark.

Rather than AI tools replacing workers, attorney and shareholder with Ennis Britton Co., L.P.A. Ryan LaFlamme sees a future where AI will not replace jobs, but rather people with AI training will accquire the jobs of people without it.

“AI is not going to take a lawyer’s job, but a lawyer working with AI, who understands how to use it effectively, is going to replace a lawyer who doesn’t know how to use AI,” LaFlamme told Spark.

Whether or not companies will adopt AI programs to enhance their work depends on cost versus benefit according to business professor at the Lindner College of Business at the University of Cincinnati, Dong-Gil Ko.

“It is uncharted territory right now. [Companies] do not really know how much [using AI programs] will cost until they really dive into it.” Ko explained. “So, they take little baby steps to implement it and get the understanding of it. If the benefit is going to outweigh the cost, certainly [businesses] will implement [AI tools]. If it is the other way around, they will have to restrategize.”

As for the future of AI, Pethokoukis holds the perspective that AI will assimilate into society. If he cannot beat them, then he will join them.

“Young people will grow up in a world where AI is a part of almost everything: jobs, education, and even how we communicate,” said Pethokoukis.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Lakota East High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs!