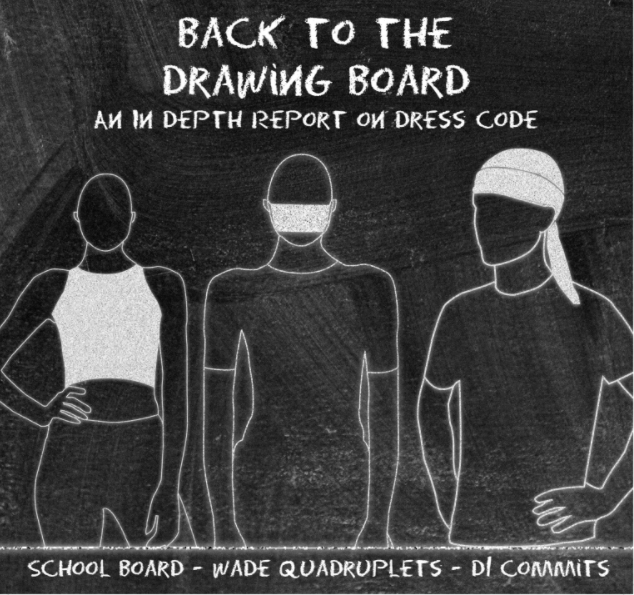

Back to the Drawing Board

Members of the East student community started initatives to reform the school dress code.

December 28, 2021

STORY MIA HILKOWITZ, ABBEY BAHAN AND MARLEIGH WINTERBOTTOM

INFOGRAPHICS KAITLIN DWOMOH, MIA HILKOWITZ, NATALIE MAZEY, MARY BARONE AND ISHA MALHI

Dress Code at East

The room was brimming. There wasn’t much room in the second-floor classroom that doubled as the Junior State Alliance (JSA) meeting room. Students were animated. Students were engaged. Students were debating.

One student took out a pair of scissors and snipped off the bottom of their shirt. The student wanted to make a point about dress code –the most debated topic at East as the school year started.

The topic of dress code was fresh in students’ minds that week. Since the beginning of the 2021-22 school year in August, announcements regarding appropriate coverage of shirts and undergarments found their way to students through intercom speeches and blurbs in the weekly T-Hawk Newsletter.

One person leading the discussion surrounding the dress code at East is senior Kay Kay Baloyi. The president of the East Black Student Union (BSU) and Women’s Empowerment Club, Baloyi has led efforts to reform the East dress code this year and to get the community talking about how the policy can change. She says that in her experience, the push around the dress codes is not about clothing–it’s about respect for students.

“It’s not like the dress code [verbatim] tells people that you get treated differently based on your appearance,” Baloyi told Spark. “But if [people think] your appearance is not appropriate, you’re not allowed to be in a certain space and allowed to have the same rights as everybody else to have an education.”

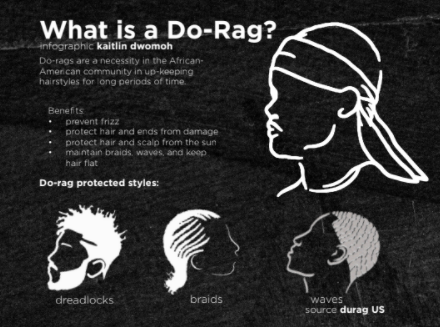

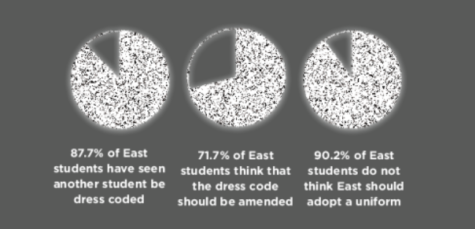

A Spark dress code survey of 81 students reported that 87.7% of East students have seen another student be dress coded. Changing the impacts of dress codes on students is a goal that Bayoli used to spur action at East through her leadership positions. This year, Baloyi started a petition through the BSU to “unban do-rags” from the school dress attire. East BSU’s petition earned 607 student signatures in the first two days.

“It happened in front of me where a black guy was wearing a do-rag, and [an administrator] said ‘take that off, you’re not allowed to wear it.’ I remember seeing him have to take his do-rag off,” Baloyi says, who notes that in her experience, white students have worn do-rags at school without being dress coded. “Black students wear do-rags to protect our hair, to restore the natural curvature of our hair, or to create a hairstyle. So him taking it off is exposing the process of our hair.”

CBS affiliate in Tulsa, Oklahoma News On 6 says that there are a multitude of benefits that come from wearing a do-rag including maintenance of hairstyles, enhancement of moisturizing products in hair, protection from sun damage, and absorption of sweat. The do-rag was first recognized as beneficial for hair during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s and has gained popularity since then.

CBS affiliate in Tulsa, Oklahoma News On 6 says that there are a multitude of benefits that come from wearing a do-rag including maintenance of hairstyles, enhancement of moisturizing products in hair, protection from sun damage, and absorption of sweat. The do-rag was first recognized as beneficial for hair during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s and has gained popularity since then.

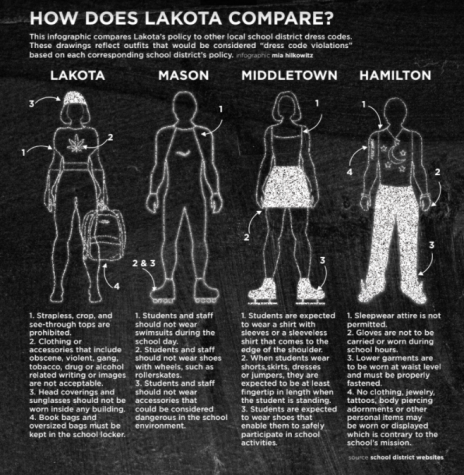

The Lakota Code of Conduct states that head coverings should not be worn inside any buildings, except for head coverings worn for religious reasons.

“We want to make sure that there’s nothing that is racially slanted in [the dress code],” East principal Rob Burnside told Spark. “But I also know that from a standpoint of do-rags, bandanas, and headbands, [administration has] addressed [zero students] related to that this year. I can’t say that a teacher or somebody hasn’t said something to someone about that, but I know from an office standpoint, we’ve not dealt with a single student and asked them to remove a headband, do-rag, or hat.”

Impact of Dress Codes Outside of the Classroom

According to the Columbia Law School Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies, disciplinary dress codes have historically had skewed effects on minority groups. Baloyi has experienced the emotional effects of these dress code policies.

“Dress code is directly tied to rape culture,” Baloyi says. “If we’re telling a girl in front of a class that her shoulders are distracting, you’re basically telling all the men in the class that you are allowed to look at them differently based on what she’s wearing. This leads to men feeling like a woman is wearing something that’s suggestive to their definition and that they can do whatever they want because it gives them permission to treat her differently.”

According to a Spark survey, 58.3% of East teachers feel that clothing distracts from the learning environment. On the other hand, East junior Julisa Muñoz is in support of the school dress code and believes that students should be conscientious about what they wear in order to maintain professionalism.

“This is a learning environment. So there’s bodily freedom in the sense that if you’re at home you can dress however you like,” Muñoz told Spark. “But once you get into a public area where other people can see, you have to be professional in the sense that you know the way you dress is affecting other people in some way or another.”

East junior Jay Baker disagrees. She thinks that bodily freedom shouldn’t be limited to just at home.

“Yes, [the dress code infringes upon my freedom] because we are at school learning how to become adults,” Baker told Spark. “[Adults] are not told they can’t wear certain things so, in school, me wanting to wear certain things shouldn’t affect anybody else.”

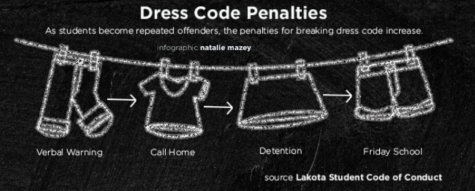

According to a recent Spark survey, 24.7% of East students say they have been dress coded at East. 15% of students say they have been dress coded one time, 6.3% of students say they have been dress coded two times, and 5% of students say they have been dress coded more than three times. Students reported several reasons behind the violation including wearing a tank top, shoulders showing, crop tops, and wearing a beanie.

Brock University Child and Youth Studies Professor Shuana Pomerantz says that historically dress codes, even outside of the school setting, have had similar effects on a range of minority groups.

“Regulating students’ bodies is also another way of perpetuating white, heterosexual, middle-class values, as most dress codes conform to a certain kind of femininity and masculinity that does not take into account cultural, racial, religious, gender, and sexual differences among students,” Pomerantz says. “It’s a form of conformity rather than diversity. While school administrators often feel that dress codes create a safe environment in schools, it can actually have the opposite effect of making minority students, and those who see themselves outside of middle-class culture feel unsafe.”

In the last several years, nationwide cases surrounding head coverings and hairstyles in dress codes have gained widespread attention. For instance, in May 2020, Everett De’Andre Arnold and Kaden Bradford filed a lawsuit against the Barbers Hill Independent School District in Texas to challenge its hair policy. De’Andre and Bradford had to cut their natural locs or else they would no longer be able to participate in regular classes and school activities, which included De’ Andre’s graduation ceremony. The petitioners gained the support of the U.S. Department of Justice and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for their ongoing legal battle.

Even with changes in legal precedent, Baloyi says that in her experience, underlying messages enforced by these types of dress codes have negative effects on students.

“I feel like a lot of the times that dress code kind of perpetuates these European standards of beauty, and a lot of the times, black culture is excluded from that or black people are forced into fitting that standard and what society thinks is appropriate,” Baloyi says. “When you’re telling me that I have to take off my do-rag, you’re telling me that my culture is not appropriate or that it is not as important as your culture.”

East junior Lucy Carlin says that she has seen disproportionate effects of dress code for students during her academic career, specifically when it comes to body size.

“It seems that girls who have bigger boobs or larger stomachs who wear crop tops get dress coded more than girls who have smaller boobs and smaller stomachs [who wear the same things],” Carlin told Spark. “It’s not fair.”

However, Carlin says that she still views the dress code as important for some aspects of the school environment.

“[The dress code] is there to make sure that people don’t wear things that are discriminatory or offensive or things like that,” Carlin says. “It is to make sure that people don’t come to school naked.”

The Lakota Code of Conduct states that “Clothing or accessories that include obscene, violent, gang, tobacco, drug or alcohol-related writing or images are not acceptable. Items of clothing that belittle others may not be worn.” Burnside says that the dress code also serves at East to prevent school violence or offense to other staff and students.

“You can’t have a shirt that promotes drug, alcohol or tobacco use, things of that nature,” Burnside says. “[Students] can’t wear anything which is offensive, bigoted or slanderous.”

Ohio American Civil Liberties Union Representative Elena Thompson agrees that dress codes can still benefit students in the school setting.

“There are good things the dress code serves,” Thompson says. “One of those things is making sure that students can feel safe to express themselves within reason and making sure that students don’t feel threatened while they’re at school. Those are effective strategies for dress codes.”

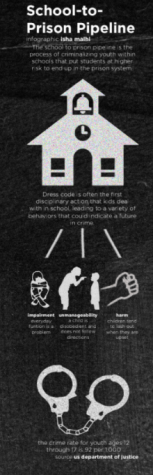

The connection between school safety and dress code is relatively new. Hamline University Education Professor Letitia Basford has spent several years studying a phenomenon known as the “school to prison pipeline.” This pipeline is a trend in which children are funneled out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Basford says that oftentimes zero tolerance policies, including dress code, are a strong contributor to the school to prison pipeline.

“Sometimes [zero tolerance] behaviors are important because they must address something that’s life threatening,” Basford says. “However, sometimes they’re very misunderstood like a dress code or a butter knife that was accidentally left in a lunchbox.”

Thompson says that dress codes are one of the strongest contributors to the phenomenon.

“[Dress code] is actually one of the strongest contributors to the school to prison pipeline, mostly because the dress codes and grooming codes are one of the more frequent ways that students are singled out and referred to discipline in schools,” Thompson says. “Many dress codes, whether its intended or not, tend to have a disproportionate negative effect on students of color, women, and generally minority students because dress codes at their center tend to be catered to white cisgender male students, primarily because those are the people who wrote most of the dress code.”

Still, many people argue that school dress codes and uniforms instill important principles such as discipline that students can use outside of the school doors. Bishop Fenwick High School Principal Blane Collison says that the uniform attire is an important aspect of school culture at the southwestern Ohio private high school.

“Students don’t have to worry about what they are going to wear. Also, [uniforms] eliminate the awkwardness for some students who would not be able to afford ‘stylish or fashionable’ clothes and creates disparity among the student body,” Collison says. “There is solidarity and a sense of belonging since everyone is in a uniform.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the percentage of public schools nationwide requiring students to wear school uniforms increased from 12% during the 1999-2000 school year to 21% during the 2015-16 school year.

“I’ve been in schools where uniforms are required and others where they are not,” Collison says. “So long as there are many various styles of uniforms, I think uniforms create a more disciplined atmosphere, and research shows [students that wear uniforms] tend to perform better academically.”

A 2016 study titled “School Discipline, School Uniforms and Academic Performance” by the International Journal of Education Management found that the highest-performing students tended to be the most disciplined in schools. Additionally, countries where students wore school uniforms found that students listened significantly better, there were lower noise levels, and lower teaching waiting times with classes starting on time. A Spark survey reported that 90.1% of students do not think East should adopt a school uniform policy.

On the other hand, East junior Johannes Fernholz says that the implementation of dress codes can hinder students’ individuality.

“Being able to wear the clothing you want is a form of showing who you are,” Fernholz told Spark. “It’s part of your personality. I think mandating uniforms takes away from your personality and your ability to be who you want to be.”

Reflection of Dress Code in the Workplace

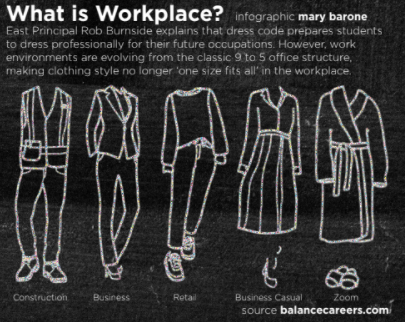

Like Collison, Burnside believes that the implementation of a school dress code can prepare students for life and the workforce past graduation.

“To me, the purpose of the dress code is helping students be future ready. The reality is that most [students] are going to enter the workforce in fields where there’s a certain level of expectation placed upon you for your appearance,” Burnside told Spark. “Number one is, if we’re going to help our students be future ready, then it’s a good idea for us to reinforce that idea that the world does have expectations of you.”

Assistant Manager of the Liberty Center Old Navy store Destiny Pelfrey says that, although she does not necessarily agree with what a lot of the school dress codes are, she does think that it could be helpful to prepare students for the future. Her stance is due to her experience as a manager of different environments.

“I just transferred stores. At my old store, the dress code was taken very seriously, and at my new store, it wasn’t. So when I got there, my mind was blown at the amount of kids that I saw in sweatpants and sweatshirts coming into work,” Pelfrey told Spark. “When they show up in sweatpants and a sweatshirt and hair in a messy bun, they just mope around. They don’t want to be here, and they don’t feel productive. They don’t look like they’re at work. They don’t want to do their job. I feel like when you get ready and you show up to work, then you are more productive.”

Part Time Manager at the Liberty Center Build-A-Bear Store Marie Hickman says that, although dress codes play a positive role in the workplace environment, it can limit individuality.

“I feel like [dress codes] create a sense of uniformity, and it kind of sets the standard for the business,” Hickman told Spark. “When I worked in places where I didn’t have to [follow]dress codes, there was a lot more individuality, and you can really see more of the people that you work with. As far as workplace dress codes, they’re always probably going to be guidelines. So I feel like allowing young adults to express their individuality is important.”

Manager at the Liberty Center Graeter’s Scott Aggel disagrees.

“I wouldn’t say that [dress code] has a significant effect on the workplace environment,” Aggel told Spark.

However, Baloyi says that the term “workplace appropriate” is too subjective to apply to a school dress code.

“Workplace appropriate, what does that mean exactly?” Baloyi says. “People work at Hooters and that’s a workplace. The tight clothing and the short-shorts, that is considered as workplace attire at hooters. Even working at a strip club, that’s a workplace and what they wear is workplace attire. So what exactly does it mean to be workplace appropriate?”

While not all workplaces require the same attire, Collision says that wearing a school uniform during one’s academic career can also instill a sense of discipline that he views as helpful for life after graduation.

“While our students don’t always like the uniform, I think they would tell you that it helps them to build self-discipline in the long run,” Collison says. “They tend to think about what they wear in public when they don’t have to be in uniform. Realizing how you look has a lot to do with how you act and how you perform at a job.”

Muñoz agrees that school uniforms are a better option because it is overall easier. She says that with uniforms, she wouldn’t have to spend time picking out clothes that go along with the dress code. However, East student Olivia Lockett thinks that instead of defaulting to uniforms, the administration should revise the dress code.

“I think [administration] should honestly ask students about it and see their own opinion on what we should have [for a dress code],” Lockett told Spark. “The students are the ones that have to follow the dress code so it’s best to get their opinion on it.”

Mason City Schools Public Information Officer Tracey Carson notes that the Mason dress code was revised in 2019 to allow more student freedom and expression. Now, instead of restricting specific clothing such as jackets and hats, the dress code has been modified to rather require students to wear a shirt that covers the front, back, sides under the arms, and the midriff when standing as well as bottoms and shoes. Under this dress code, Mason students are restricted from wearing violent language or images, images or language depicting or suggesting drugs, alcohol, vaping, or paraphernalia, clothing that reveals visible undergarments, shoes with wheels, swimsuits, and accessories that could be considered dangerous.

“[Dress code] is a place where we wanted to make sure that we were being as inclusive as possible,” Carson told Spark. “We want all of our [students] to know that they’re an important part of the Comet community. We also understand that the way we choose to dress and present ourselves is an important part of our identity and development in general.”

Another aspect of Mason’s broad dress code is learning to accept differences.

“The biggest thing is that we want kids to feel like they’re ready and prepared to learn,” Carson says. “Sometimes that means getting used to what someone else is wearing, but in a way that can also be a learning experience to promote discussion.”

Can/Should the Dress Code Change

Pomerantz says that many school districts have had success reforming their dress codes by communicating with the local community. For instance, the Toronto District Schools in Canada adopted a new dress code policy for the 2019-20 school year following concerns around racist and sexist wording within the dress code policy.

“I think teachers and administrators need to talk to male and female students and ask them what’s comfortable, what makes sense, what fits with youth culture, what isn’t discriminatory based on gender, race, or sexuality, and what works best given the specific school environment,” Pomerantz says. “What one student body votes for may be different than another student body at another school. But the main thing is not to assume young people don’t know anything by keeping them out of the conversation.”

In addition to changing any potential discriminatory wording within the policy itself, Pomerantz says that changing how dress code is enforced is another major step to reform.

“[The best way to handle a situation when a student is dressing inappropriately] is not to shame or embarrass them, call them out in public, or punish them,” Pomerantz says. “The best way to handle an issue of dress is by talking and asking the student why they wanted to dress that way, listening to them, and trying to see their side of it.”

A Spark survey found that 71.1% of students feel that the dress code should be amended, and 59.5% feel that the dress code should be abolished. Bayoli agrees that changing the enforcement aspect of the dress code would benefit students.

“I think that’s the problem, when you do it in front of everyone,” Baloyi says. “If teachers see something wrong with the student’s dress code, we would have preferred for them to go and handle the matter privately instead of saying it in front of everyone, and basically embarrassing them and still perpetuating this idea that you can address somebody differently based on what they are wearing.”

According to a Spark survey of 24 East teachers, 70% of East teachers surveyed have not had to discipline a student for a dress code violation. Additionally, 91.6% feel that the dress code is not effective and 60% believe that the dress code should be amended.

One anonymous teacher who feels that the dress code is not effective describes the current student attire situation as “absolutely out of control.”

Another anonymous teacher noted that, while they have had to previously discipline a student for a dress code violation, that “I should [enforce the dress code]. I don’t address it.”

In the same Spark survey another anonymous teacher said that, in regards to disciplining students for dress code, “I won’t be backed up, so I don’t [discipline students for dress code].”

Basford says that updating bias training for teachers can also help minimize the impact of the school to prison pipeline.

“Families need more support and these kids need more support. We need to do more to keep kids in school and support their families,” Basford says. “We need incredible training for our teachers. We need to become aware of our hidden or sometimes not so hidden bias. We need to know when we’re hyper disciplining one student for something that’s exactly the same as what some other kid is doing, but we’re not treating it the same way.”

Burnside notes that the best way to bring issues regarding dress code to light is by notifying administration.

“If you see something, if you send it to the office, we are going to support you as an administrative team with the messaging. We’ll have those hard conversations,” Burnside says.

For Lakota, changing the dress code at East is not only a building decision, but also one that concerns the entire district, Burnside says.

“At Lakota, we have one code of conduct so that we’re consistent between our multiple high schools, so we would really have to pull the team together to have a discussion,” Burnside says. “We couldn’t make a change that they didn’t make at [Lakota] West.”

Additionally, Burnside says that changes to the dress code policy take time due to the process for code of conduct approval.

“For us to be making changes to the code of conduct, things of that nature [including] dress code, generally you have those discussions in March and April,” Burnside says. “The code of conduct goes to the Board for Board approval in May. We wouldn’t be changing the code of conduct now because it’s been board approved for this year, we would have to make those changes for next year.”

Thompson says that including students and community members in the conversation surrounding dress code reform can be beneficial.

“While dress codes are protected by the First Amendment, they are specifically crafted by local governments or school boards,” Thompson says. “Oftentimes teachers or teacher’s unions have power to negotiate dress code. Parent Teacher Associations and students themselves have power to actually influence what goes into their dress codes.”

In her efforts with East BSU and Women’s Empowerment club, Bayoli feels that in order to achieve appropriate reform within the school, more than just policy wording needs to change.

“I think the narrative has to change,” Bayoli says. “I think that the narrative as a whole, like how you are addressed and whether or not it’s appropriate, whether or not it’s workplace appropriate, needs to change. And as soon as the narrative changes, the way that students are dress coded changes.”

History and Legal Aspects of Dress Code

The debate surrounding dress code has long been discussed in American culture. According to research institution ProCon, an institution based in pro and con format to demonstrate both sides to arguments, the origin of the modern school uniform can be traced to 16th Century England when impoverished students, referred to as “charity children”, attended the Christ’s Hospital Boarding School. Their uniforms consisted of blue cloaks that were reminiscent of cassocks worn by clergy members. However, the implementation of dress code was strengthened through the use of government-run boarding schools for Native American Children in the 1800s, where children were removed from their families and dressed in military-style uniforms in an effort to “christianize” the youth.

Pomerantz says the cultural impacts of these origins have been maintained in modern American society.

“The issue of dress code is political because we treat people’s bodies as political,” Pomerantz told Spark. “The body is always bound up in other socio-cultural issues.”

In 1987, the first U.S. public school implemented a voluntary uniform policy as a response to a 1986 Baltimore shooting, in which a local public school student was wounded during a fight over a pair of $95 sunglasses. As more schools across the nation adopted uniform or stricter dress code policies, Seattle University Law Professor Deborah Ahrens says that the topic of regulating student attire became more politicized. For instance, in 1996, former President Bill Clinton told Congress during his State of the Union speech that, “If it means that teenagers will stop killing each other over designer jackets, then our public schools should be able to require their students to wear school uniforms.” By publicly supporting this policy for his presidential re-election campaign, Clinton helped politicize the topic of dress code policies in the U.S. and draw attention to the subject.

“We would have thought of [the Clinton administration] as Republican or more conservative,” Ahrens told Spark. “[Clinton’s administration] made [dress code] a centrist mainstream position that both Democrats, Republicans, and independents agree on.”

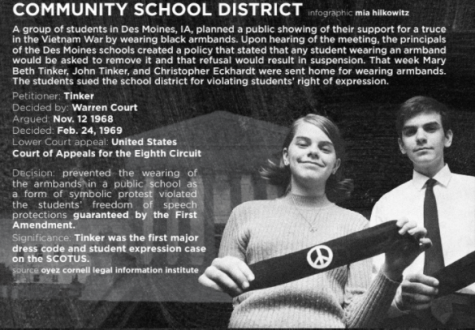

As regulation of student attire increased nationwide, legal cases challenging restrictions followed suit. According to Thompson, one of the most significant cases used to set precedent for dress code legal cases is Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969).

“Essentially, the court held [in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District] that students still have a right to free speech at school, and they have a right to free expression at school,” Thompson told Spark. “Obviously, this right isn’t completely expansive. It can be limited in some circumstances. But when there is no threat to actually disrupting the classroom atmosphere, students should have a right to express themselves.”

In the case Tinker v. Des Moines, a group of students in Des Moines, IA, planned a public showing of their support for a truce in the Vietnam War by wearing armbands to school. Upon hearing of the meeting, the principals of the Des Moines schools met to create a policy that states that any student wearing an armband would be asked to remove it and that refusal would result in suspension. That same week, siblings Mary Beth and John Tinker, along with classmate Christopher Eckhardt, wore their armbands and were sent home. The students, through their parents, sued the district for violating their right of expression. The court found that the restriction did violate the students’ rights under the first amendment and that students did not lose these rights when they entered “the schoolhouse gates.”

However, the precedent set in this case more than 51 years ago can still be limited in certain cases within the school setting.

“Even if students do have some first amendment rights, they are not the robust version of rights that adults enjoy,” Ahrens says. “In theory, [schools] have these other things that they need to balance against those constitutional rights.”

One key aspect that school officials consider while developing their dress code is balancing student expression with safety on campus. Basford says that this concern has often resulted in “zero tolerance policies” at schools, or school discipline policies and practices that mandate predetermined consequences in response to specific types of student behavior.

“Zero tolerance policies were a reaction to Columbine and other school shootings,” Basford told Spark. “We became really hyper militant about certain actions in schools and zero tolerance policies which have expanded to include a lot of things, not just guns. That was when we really started to see a lot more kids being expelled and suspended without any kind of humanity involved in that decision.

Zero tolerance policies often include dress code or uniform policies. Currently, East does not maintain a zero tolerance policy towards dress code. For many school districts across the nation, Thompson says that developing a dress code that balances student rights with key aspects such as safety and professionalism has left room for discrimination within the policy.

“One of the major forms [of discrimination] that we tend to see is sex discrimination in dress code. There is pretty solid guidance and court cases that suggest that schools cannot have dress codes that are segregated by sex,” Thompson says. “There has to be one cohesive dress code that applies to all students.”

In August 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit ruled that a North Carolina charter school’s dress code, which requires girls to wear skirts and bars them from wearing pants or shorts, is a violation of Title IX. While Title IX can prohibit discrimination within the specific wording of a school’s dress code, Ahrens says that dress codes have still been able to discriminate based on gender.

“Title IX protections against sex discrimination ought to protect you against gender based dress codes and a lot of these dress codes do indeed have gender specific language,” Ahrens says. “You can have restrictions on rights that are not specifically targeted at boys or girls in their language that nevertheless are only going to affect one gender.”

In addition to gender discrimination, Thompson says that dress codes have also been discriminatory by race throughout history.

“One thing that we frequently see is dress codes that are discriminatory by race,” Thompson says. “One example of this is a dress code that says that hair cannot be braided, kept in a protective style, or be less than an afro. Obviously, that discriminates most prevalently against students of color. While those sorts of dress codes on their face aren’t calling out students of color specifically, they have a really specific impact on students of color.”

Additionally, Thompson says that schools have to balance regulating content among attire.

“Schools generally have a pretty broad right to prohibit students from wearing whatever they want, but they can’t prohibit things based on content or viewpoint alone,” Thompson says. “So a school can say you can’t wear any hat and that would be okay. But a school specifically can’t say you can wear a hat [because] your hat says MAGA or is an LGBT ally hat.”

Thompson says that the subjectivity surrounding discrimination in dress code has made it difficult to legislate.

“There is not currently any legislation about dress code specifically, but there’s a ton of legislation about students and student rights,” Thompson says. “Dress code specifically is generally not really looked at in Ohio, and this is mostly because the state tends to avoid legislating issues of student expression.”

While the specific laws regulating dress code have not changed, East principal Rob Burnside says that the way that dress codes in schools are enforced has still adapted over the last several decades.

“Things that might have been considered acceptable when I started teaching 27 years ago, are different from what they are today,” Burnside told Spark. “Society’s changed and evolved, and expectations have changed with it.”

Lakota East student Gigi Pisano is also in support of East’s dress code to a certain degree, but she thinks that its major fault is how it’s enforced.

“[The dress code] is unreasonable and a little bit flawed.” Pisano told Spark. “That’s because of how they enforce it. It’s either super extreme or they don’t do anything at all.”

Burnside adds that the enforcement of dress code was much stricter in past decades than it is with the current East administration.

“20 years ago when I was teaching here, I remember our administrators standing out front of Main Street and if a kid walked in wearing a hat, they would take their hat right there,” Burnside told Spark. “We don’t do that anymore. Could we? Yeah, because the [Code of Conduct] says we could, but ultimately it comes back to is it a disruption to the instructional process. And in this day and age is it really a disruption to a class if a person wears a hat?”