STORY AND INFOGRAPHIC MARLEIGH WINTERBOTTOM

PHOTOGRAPHY RILEY HIGGINS

For the first 10 years of her education, East senior McKenzie Watson spent everyday in her familiar school desk and chair, listening as her teacher gave instruction. Now, as she wakes up at home every morning and opens her school-issued Chromebook computer, the pixelated screen of Canvas with her materials and assignments is the only tie between her education and East.

“[Going remote] was a big adjustment. I felt a little bit behind starting off because I didn’t have that one-on-one interaction with my teachers as often as I would have liked,” Watson told Spark. “It was just hard knowing that they had other students as well. So sometimes, a lot of my questions wouldn’t get answered until days later, when I would have already figured it out because I had to turn the assignment in.”

Due to the challenges of online learning, many students experienced a gap in education. In a Spark survey of 170 East students, 74% of students felt that the COVID-19 pandemic affected their academic growth and/or achievement. Additionally, 86% of students felt they did not learn content from remote learning at the same capacity they would have if it were in-person instruction.

“[An education] gap was felt by everyone, everywhere,” Lakota K-6 Director of Curriculum & Instruction Christina French told Spark. “I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that not only were we virtually learning, which was new, but we also had students in and out of classrooms.”

East Principal Rob Burnside agrees that an education gap was felt, and it is something Lakota is aware of.

“I think every school has experienced [a gap in education],” Burnside told Spark. “The data we have from testing has indicated that there was a drop, and I think that this is something we have to be very aware of to try to play catch up.”

Ohio State University Admissions Counselor Austin Martin commends students who have had to do online coursework the past few years due to COVID-19.

“I took two online courses in college, and I said never again; that was challenging enough,” Martin told Spark. “Now, a whole class had to do a whole semester or a whole academic year online. That would be the most challenging thing I probably would ever have to go through.”

But, for some students, their decision to go remote had nothing to do with preference, it had to do with logistics.

When given the chance for the 2020-2021 school year to return to in-person instruction, Watson and her family chose to stay remote to protect her immune-compromised sister, taking advantage of Lakota’s Virtual Learning Option (VLO).

“I kind of knew that if I decided to stay VLO, it would be strictly independent learning, and I wouldn’t get as much help as I would being in school and getting that assistance from a teacher in-person,” Watson says. “I knew I would be giving that up, but it was a sacrifice I was willing to make.”

However, Lakota had a different education experience for the 2020-2021 school year than most schools across the country because students were still given the choice to return to in-person learning.

“I don’t think [the lockdown] affected us as much as it might have in other school districts,” Lakota 7-12 Director of Curriculum and Instruction Andrew Wheatley told Spark. “Many schools across the country were 100% virtual for all or part of the year, and we were one of the few schools that were actually able to stay in person for the majority of our students for the whole year.”

Burnside agrees that Lakota handled the lockdown better than many districts, but there is still room for growth and change.

“One thing we have to keep learning about, that we still struggle with institutionally, is remote learning,” Burnside says. “You can’t just simply replicate what you do in the classroom.”

One challenge brought upon by VLO was students abusing the virtual option as a way to cheat through coursework.

On an anonymous East teacher survey, 64.9% of teachers surveyed reported encountering issues with cheating in their VLO classes. 8.1% of respondents said they did not have an issue with cheating. The remaining 27% of survey respondents did not have a VLO class to comment on.

“We’re trying to replicate what we do in the classroom and it doesn’t work because we no longer have the ability to stand over their shoulder,” Burnside says. “I think some of that is partially a flaw with our lesson design because it makes it easy for people to work around it. What if instead, we give them that information and have them post to a discussion board? Now, they’re engaging in higher levels of learning and we’ve eliminated the need to cheat.”

As a VLO student, Watson was presented with another challenge: she wasn’t able to access the same resources as in-person students.

“I feel like VLO students have it a tad bit harder since we don’t have access to the same tools, immediately, as the in-person students have,” Watson says. “I feel like that does cause a bigger gap for VLO students.”

Penn State University Admissions Counselor Jordan Garrigan has found through students’ applications that several students note the same difficulties with gaining resources in an online setting.

“The only difference [in applications] that I have heard from students and through reading essays is that they don’t have as much access one-on-one with their teachers,” Garrigan told Spark. “I have noticed that the extra help that students usually get when they’re comfortable in the classroom is not as great as it was whenever they’re on Zoom.”

For Watson, independent learning affected her differently in different subjects.

For Watson, independent learning affected her differently in different subjects.

“In some subjects, I felt like I might have been a little bit more behind, and, in other subjects, I might have been a little bit more ahead,” Watson says. “To give an example, I felt like I was ahead with English, Psychology, and Sociology, and I felt like in Math, I might have been a little bit more behind than my other classmates who were in-person.”

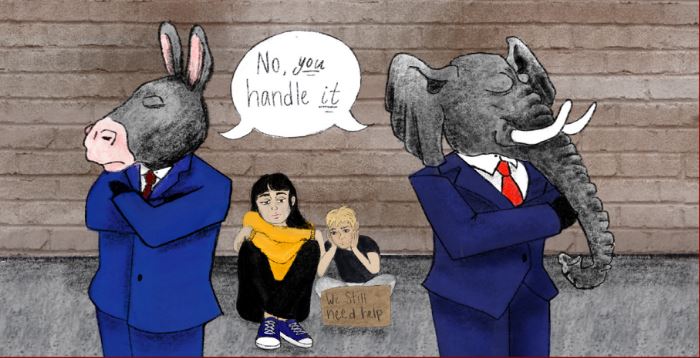

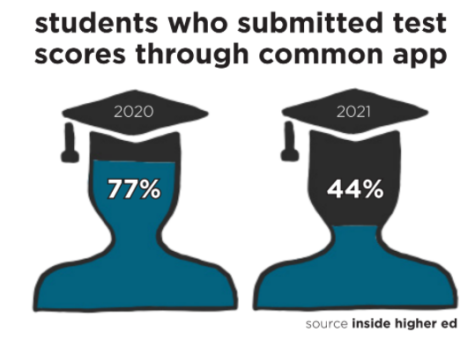

Due to students being in varying places in their education and testing facilities being limited due to the pandemic, many colleges, including Penn State and Ohio State, have had to adjust their usual ACT and SAT score protocols.

“As far as the admissions process, we’ve definitely had to be flexible with a lot, such as changing deadlines and utilizing students’ time properly. We understand that there are circumstances where students have a test that was taken in November, so we had to extend that deadline to Nov. 15,” Garrigan told Spark.

Both universities decided to remain test-optional to allow students flexibility with these unprecedented times. Approximately 60% of Penn State and 53% of Ohio State class of 2021 applicants chose not to submit test scores on their applications.

“I think [waiving test scores] is a good idea for students who don’t necessarily want to have to go through the process of retaking the ACT because it is stressful, but for students who know that retaking the test is something that they can do and have the time for, I think it’s a good idea to pursue [submitting scores],” Watson says.

Even though some students did not provide their test scores to Penn State or Ohio State, they are still guaranteed the same level of consideration as students who submitted test scores. Ohio State ensures this by having separate admissions counselors to review applications without test scores as they do applications with test scores. Penn State applications are not reviewed separately; however, they instead focus on other aspects of the application, such as activities, to consider acceptance.

Penn State has extended their test optional policy for two years until 2023, whereas Ohio State is still currently test optional, but has chosen to take it year-by-year in regards to continuing the policy.

“I think what Ohio State, our leadership team, and a lot of the leaders in our office and undergraduate admissions have said is that we want to give these two classes the best opportunity for admission,” Martin told Spark. “If more opportunities arise, and if the world starts to open up more, I think Ohio State might shift back to requiring those test scores. We want to do what’s right for the student first and then we want to make it work for Ohio State; that’s our motto.”

Although the past few years of schooling have not been ideal to many, Burnside notes that it had some advantages as well. He says that Lakota’s new online approach will help students keep the educational process moving forward, even when not in the building.

“As an institution, education is now better at meeting the needs of our students who don’t function as well in a brick and mortar building, which is a good thing,” Burnside says. “[These new online advances] lead us to helping our students be better prepared for the next generation of professional work. Workers of the future aren’t going to be going to the office nine to five, every day, like they have in the past; it’s a new world.”