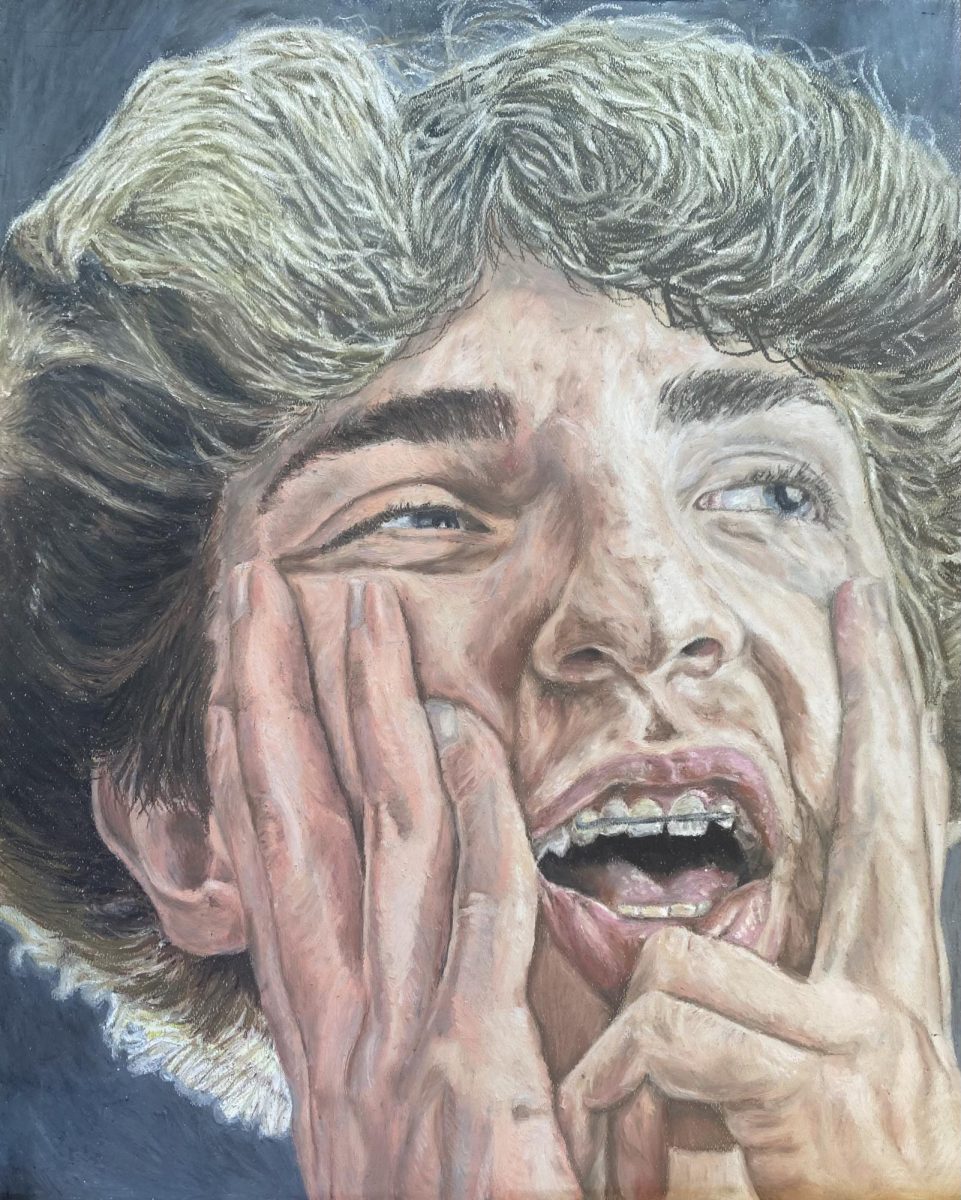

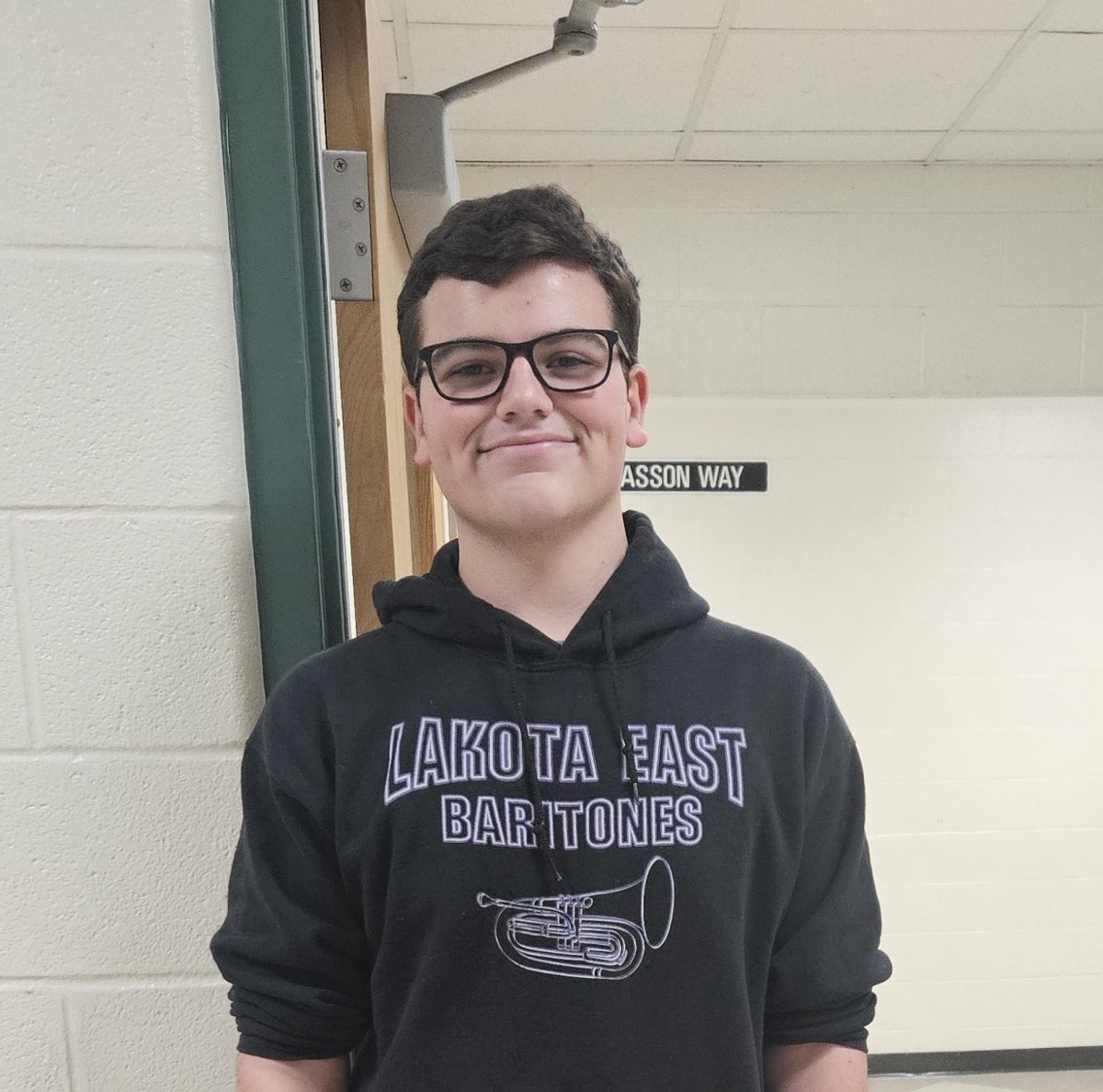

By Jennave Traore | Photography by Cara Satullo

On the first day of school, a little girl imagines just for a second what it would be like to have straight, blond hair because her dark, curly hair made her feel out-of-place. She keeps her head low to the ground, and when she looks up, she sees that the only biracial person in the room is her. For East junior Kennedee Card, growing up as a biracial girl wasn’t just about race—it was about self-acceptance.

Living in a predominantly white community, Kennedee often found herself in situations where she was the only biracial person. She sometimes feels she doesn’t connect to her black peers, not because she’s biracial, but because of her childhood environment.

According to the Census Bureau, more than 7 percent of the 3.5 million children born in the year before the 2010 Census were of two or more races, up from barely 5 percent a decade earlier. The number of children born to black and white couples almost doubled. Multiracial children are also one of the fastest growing segments of the United States population. Kennedee and Hamilton are two of the approximately two million American children who have parents of different races. There recently has been a shift in social norms and according to Gallup’s Minority Rights and Relations poll, 87 percent of American people approve of black-white marriage, versus four percent in 1958.

For Kennedee, it was sometimes difficult to be confident in who she was because a peer might casually mention her race as a negative thing. When Kennedee would leap a step forward in confidence, someone would knock her back two steps.There was a time when someone flat out told her, “you talk so white,” and from then on, if someone criticized her race, she would tell them that any race is capable of speaking well.

“I articulate my words,” Kennedee says. “If you’re biracial, why do you only have to be black or why do you only have to be white? You shouldn’t only be labeled as one [thing].”

As a volleyball player, Kennedee believes that athletes can have more than one characteristic as well. Volleyball has been a part of Kennedee’s life for only four years, yet she excels in the sport. She is also dedicated to her studies because she doesn’t allow the stereotype about athletes not being able to be intelligent to define her. Kennedee’s fellow teammate and East junior Lauren Weaver says Kennedee is a hard worker at everything she does.

“We hit it off from the start, and our personalities fit well together,” Weaver says. “I think she’s a very good athlete. I know she’s really hard on herself, and we’re hard on each other.”

Kennedee works hard toward all aspects of her life and recently she auditioned to New View Modeling Agency. Her race stood out to New View, and the agents said she worked very hard for it. But, the opportunity could have been different if she weren’t biracial. The modeling agents told Kennedee that she would add more demographics to their company by adding someone of a mixed race. Now, if Kennedee decides to sign to the company, she’ll be able to model athletic, formal and back-to-school wear. It’s an opportunity she never thought she would be able to do before.

Kennedee’s mother Holly Card is Caucasian and her father and West principal Gary Elgin Card is African American. Elgin Card wants Kennedee and her three sisters to respect both sides of their culture. At the same time, he doesn’t want them to dwell on it because he doesn’t want their race to have a say who they are.

“I try to let all my daughters know to be confident in who [they] are, treat people right and do the right things, and then more positive than negative will come their way,” Elgin Card says.

Elgin Card also knew that he would face discrimination toward his family when he married, but he has learned to deal with discrimination his entire life.

“I told my wife when we were married to be prepared for a small portion of people to be closed-minded and have an issue with [interracial couples]”.

Even though Kennedee and her family have experienced negative feedback, they are not the only ones who have experienced a form of negativity. Kennedee’s close friend, East junior Nick Hamilton, can relate to what it’s like to be biracial.

“The fact that we are both biracial adds a level to [our] friendship,” Hamilton says. “Certain people will see us as just one race. People don’t really recognize being biracial—they just recognize black or white.”

When Kennedee was a child, her grandmother used to call her Pocahontas. Her grandmother would tell her that she was just as beautiful with her long, curly hair as someone with straight, blond hair is. Now, when Kennedee walks into a room, she walks with her shoulders back and her head held high. The idea of having straight, blond hair became a thing of the past. She found out that she can wear her hair straight or she can wear it curly because either way, it represents a side of her race.

“I see both sides of the spectrum,” Kennedee says. “It shouldn’t matter what color your skin is or what color your parents’ skin is. It should matter who you are and not about what you look like.”