Story by Maddie Weikel | Infographic by Emma Stiefel

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) ruled in a 7-1 majority in favor of petitioner Abigail Fisher that The University of Texas in Austin’s admission policy too flimsily admitted applicants on the basis of race in June 2013. SCOTUS announced this past June that the case will be heard again early in 2016, and the possibility of affirmative action policies in college admissions will be placed under closer scrutiny and face the possibility of further limitation or termination.

Rooted in historical discrimination and persisting systemic inequalities, affirmative action is strongly supported by people who insist that some form of preferential race-based admissions is necessary to counteract social barriers that minority applicants inherently face. Opponents, however, preach that reverse discrimination (not admitting applicants because they are are not minorities) bars qualified majority applicants from opportunities for no other reason than because they are white. With the value of college degrees growing, the competition to be admitted to prestigious universities is heating up. The national discussion about whether race-based admissions policies align with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment also persists.

East guidance counselors Alicia Roberson, Matt Rabold, Michelle Kohler and Jennifer Millard have not had any conversations with students about affirmative action. Universities deliberately recruit students of all races by publicizing their “commitment to diversity,” so the specific language surrounding affirmative action is rare among students.

“[Affirmative action] hasn’t come up in general,” Millard says. “High school students today are generally comfortable with diversity and accepting of differences.”

Since the inception of the policy in the 1960s, affirmative action has faced opposition from conservative Americans who see the policy as elevating minority students based on criteria outside of those students’ control. While affirmative action in its early stages often resulted in universities simply instituting racial quotas, after a series of Supreme Court cases (California v. Bakke in 1978 to Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger in 2002 and 2003 and to Fisher v. University of Texas in Austin in 2013), institutions now consider race as one of many factors that determine acceptance.

Affirmative action is a process that stays behind the doors of admissions offices. To recruit not only racially diverse students but also students who have a keen appreciation for diversity, universities advertise the racial breakdown of their student bodies and construct programs like Miami University Bridges.

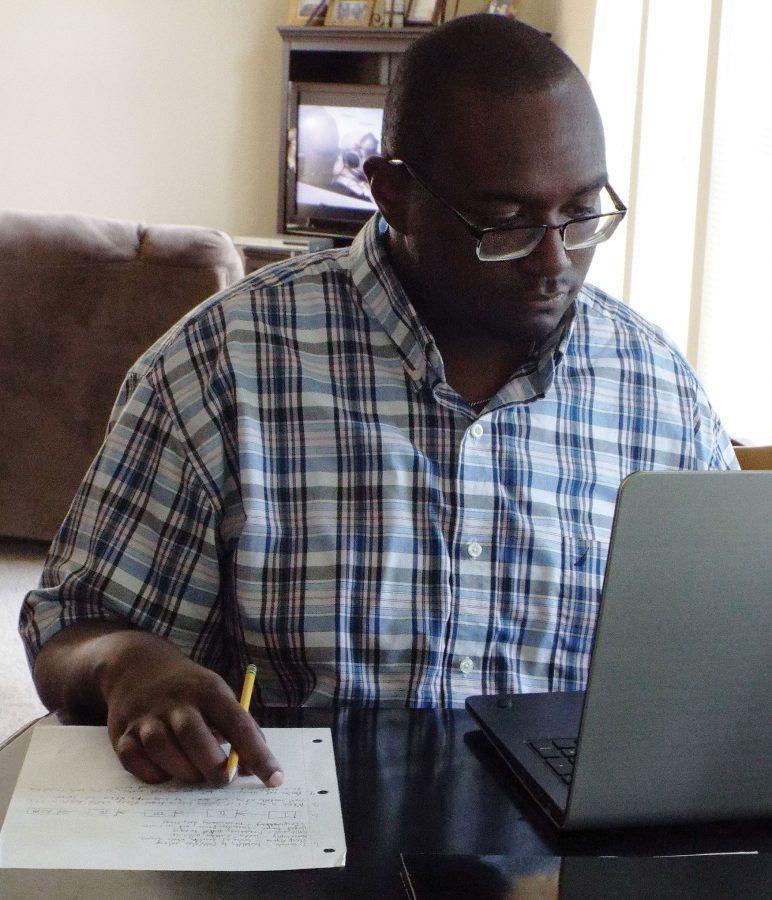

Although East juniors Chontevia Lewis and Ekene Azuka and senior Isaac Mitchell have not sought statistics about racial diversity during their college searches, the concept remains important. Lewis supports the concept that diverse ideas come from diverse backgrounds but only if the motivation to specifically admit minority is that simple.

“Using affirmative action to help people who wouldn’t have the chance [to go to college] is good, but I wouldn’t like colleges to using [affirmative action policies] to make their schools look better,” Lewis says. “Diversity in a learning environment is important to see different cultures and see what is unique about people, but if [diversity] is used just to lift up a school higher than another, then that’s not OK.”

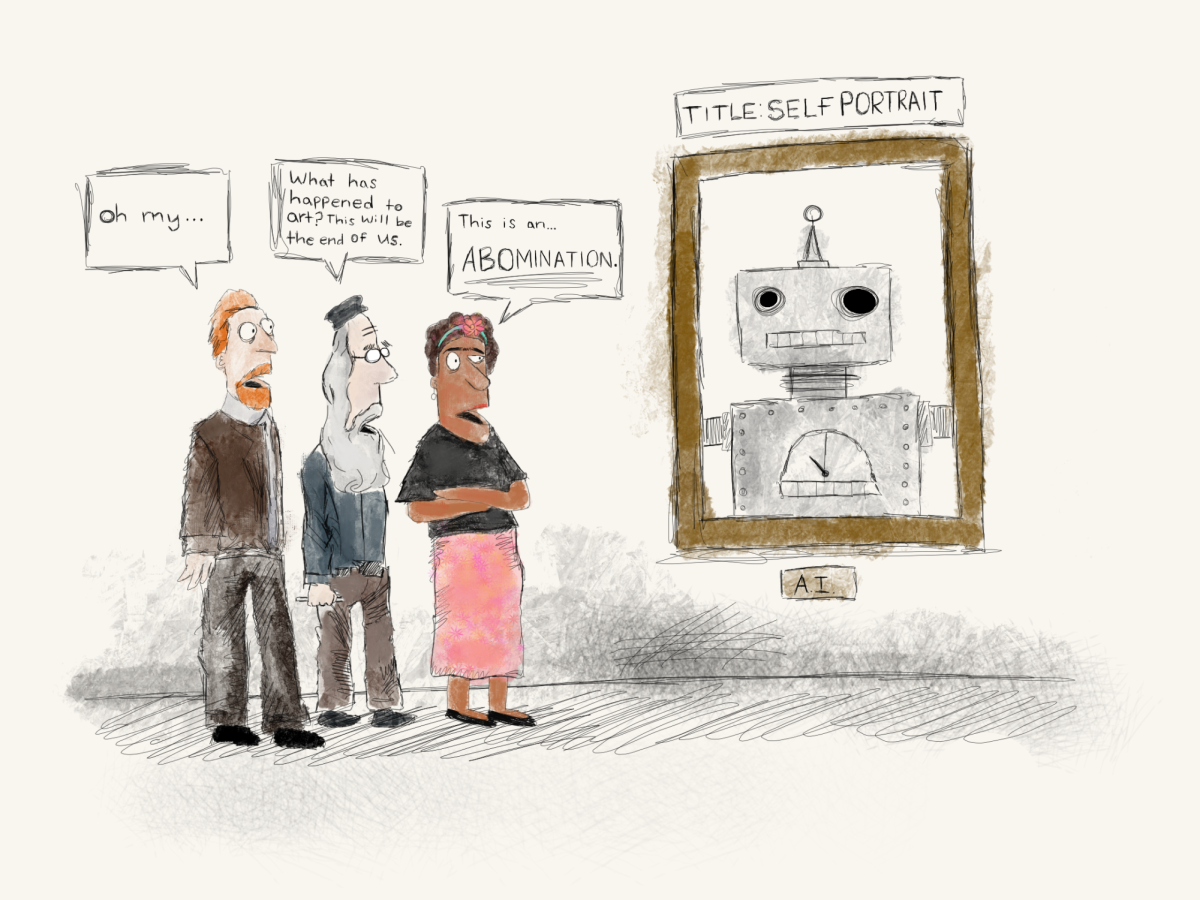

University of Chicago Sociology Professor Ross Stolzenberg tells Spark that admissions are no longer as simple as a pile for accepted applicants and a pile for declined applicants. Because highly-selective universities, which typically utilize affirmative action policies more frequently than other schools, it is more difficult to attribute a student’s acceptance to race alone.

“From the perspective of a college’s administrators, a qualified student is one who can complete the school’s academic requirements for graduation and whose presence can both help the school attract more students and enhances the ability of the college to pay its bills,” Stolzenberg says. “Admissions is a product pricing problem comparable to methods used by airlines that charge different prices for different types of customers but still put them on the same plane.”

The criteria for maintaining race as a consideration in undergraduate admissions were elevated with each Supreme Court ruling from 1978 until today. The most recent position from Justice Anthony Kennedy is that universities must demonstrate that “available, workable, race-neutral alternatives do not suffice” before using race in admissions decisions.

Despite this increasingly invasive probing into affirmative action policies, 30 percent fewer white Americans support these policies than black Americans, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center study. Out of the pool of supporters, 24 percent of respondents said they supported affirmative action because it makes up for past discrimination. Mitchell doesn’t support using the term “reverse discrimination” because the word discrimination can be used to communicate bigotry toward any and all racial groups, but he understands the concept.

“There are people like me who don’t necessarily get the best grades, and if I were of a different racial group, affirmative action could get me in over someone with the same grades as me,” Mitchell says. “We live in a racist society, so I understand the need for affirmative action, but this aspect doesn’t necessarily seem fair or balanced.”

Department of Sociology Doctoral Student at the University of Maryland Joey Brown tells Spark that militant adherents to the idea of reverse discrimination, who are far more aggressive than Mitchell, likely do not understand the historical foundation that supports affirmative action policies.

“People tend to see [affirmative action] policies as coming out of thin air without recognizing the social and historical circumstances that surround them,” Brown says. “The timeline outlining progress since discrimination was made illegal may seem long, but compared to the at least 200 years of disadvantage that minority groups have been placed under since American independence, [progress] is really not that substantial.”

Because segregation in both housing and education still persists, Brown says, historical inequality among especially low-income minority applicants creates an obstacle that even low-income whites do not have to hurdle as frequently. He notes that low-income whites tend to live in more affluent areas than their black counterparts and are therefore more likely to live in slightly better school districts.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, on average, black high school students have access to 75 percent of the challenging and college-preparation courses that white students utilize. Furthermore, the Center for American Progress found that with a 10 percentage point increase in minority students in an educational institution accompanied a $75 decrease in per-pupil funding. Even when researchers in the labor market looked to advocate for more class-based than race-based affirmative action, racial disparities tended to surface anyway.

Because the bitterness of reverse discrimination is typically taught in school and because of the claims made in Fisher v. University of Texas, discovering that a student was admitted to a university with the help of affirmative action could be stigmatizing toward both the policy and toward that student. While Brown has not seen any national data on this specific tension between minority and majority students, he has heard personal anecdotes that demonstrate its prevalence.

University of Chicago Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy Damon Jones tells Spark that this stigma is tricky in context.

“If you frame affirmative action as something a student doesn’t deserve, then it’s very natural to believe that a student who may or may not be benefitting from it to feel self-conscious,” Jones says. “There are students who are children of faculty members or children of alumni that also get preferential treatment in the application process, but it’s not made clear that they’re to feel undeserving of the benefits they receive.”

Because affirmative action is framed as policies that admit students who would not be admitted otherwise, opponents use the term “mismatch” to describe these students because they are said to be at schools that are not a match academically for them because of the aid from affirmative action. A 2014 study by Peter Arcidiacono, Esteban Aucejo, Patrick Coate and V. Joseph Hotz analyzed graduation rates at California universities following the implementation of Proposition 209 in 1998, which banned affirmative action policies in the state. Because minority graduation rates increased by 4.35 percent following Proposition 209, the general consensus was that by eliminating affirmative action, minority students were better sorted to schools that complement their academic abilities and prospects. Jones acknowledges this trend, but by adding in the factor of lower enrollment of minority students, higher graduation rates don’t necessarily tell the whole story.

While mismatching could be a genuine concern when affirmative action was strictly racial quotas, Stolzenberg says that outside of individual circumstances, that mindset doesn’t make sense in the context of modern admissions.

“There is a lot of exaggeration and fiction in [mismatching], and the statistical research needed to access it is subtle and complex,” Stolzenberg says. “Schools look bad when their students struggle academically, transfer or flunk out, so school admissions policies are generally designed to avoid those failures.”

Friction before students are even admitted, however, is the stem of the debate for and against affirmative action policies in the United States. In a study done by Harvard Professionals Roland Fryer Jr. and Glenn Loury called “Affirmative Action and its Myths,” the men explain how minority applicants who are admitted with the help of affirmative action are competing against equally qualified white applicants. It is therefore not plausible to say that an inferior minority applicant is taking an acceptance letter away from a majority applicant.

Fryer and Loury compare the situation to a full parking lot with open spots reserved for disabled drivers. As everyone who is able-bodied angrily drives in circles, cursing the handicapped spot for taking a spot away from them, they fail to realize that if the handicapped spots were open, they would already have been filled by one of the parkers.

Jones notes that people overestimate how likely they would be to get a spot if it weren’t for affirmative action. As data shows the decrease in minority enrollment as states outlaw affirmative action policies, it becomes clear that discrimination transcends the college admissions office. However, because of institutional inequalities and because of the variety of factors that determine an applicant’s admission, it is near impossible to separate race as the sole factor determining acceptance or denial.

“Affirmative action policies are instituted in acknowledgement of general societal barriers across racial groups that aren’t only due to college admissions discrimination,” Jones says. “High residential segregation results in high disparities in income and quality of K-12 education across racial groups. By the time students arrive at the application process, there may be systematic differences in their grades and test scores that surface in the admissions office but did not begin in these offices.”

Considering both the systemic and the inherent inequalities that many minorities endure in many aspects of their lives, determining whether a minority student is admitted to an institution because of race is not a black-and-white issue. Stolzenberg says that universities want students who will ultimately graduate and bring money back to the school, and any blip involving blatant racial discrimination would hinder those two goals.

Persisting and evolving along with society through Supreme Court rulings, affirmative action remains a prevalent topic among college applicants who are informed enough about the issue to have an opinion. Unless America resolves the systemic inequalities that feed the need for affirmative action, the conversation will persist.

“Racial, ethnic and religious prejudice all flourish today, but it is suicidal for organizations to discriminate in ways that show up in statistical reports on such things,” Stolzenberg says. “It is difficult to measure implicit racial biases, to assess their impact, and to know what might occur if laws changed now. Intergroup hostility seems to always be ready to become manifest on a short notice, so all this can change very quickly and unpredictably.”