story by Jessica Jones | infographic by Selena Chen | art by Alexandra Fernholz

Separated parents have been the norm for him since he can remember. His parents have been divorced since he was two years old. Switching from his mother’s house to his father’s house twice a week is his normal. His parents don’t talk to each other and send messages through their kids.

East junior Logan Kaminsky is one of the millions of kids with divorced parents. It is approximated that throughout their life, 50 percent of children will experience a parental marriage breakup.

Kaminsky’s parents have been divorced for 14 years and have equal custody. He is with his father Monday and Tuesday, with his mother Wednesday and Thursday, and alternating parents every weekend.

“I act a certain way to keep one parent happy, then act another way to keep the other parent happy. I end up becoming two different people,” Kaminsky says. “With my dad, I am more goofy and carefree, but with my mom, I am more antisocial and focused on school.”

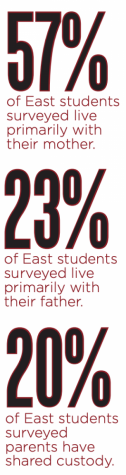

According to the United States (US) 2013 census, it is most common to see a mother take the primary custodial role after a divorce. Only one out of six custodial parents are fathers. From a recent Spark survey, 32 of the 56 students polled say they live primarily with their mom, 13 primarily live with their dad, and 11 have shared custody.

However, according to Domestic Relations Lawyer Maury White, no bias from the court system is involved when determining a custodial parent or shared custody unless there is actual cause, such as a criminal record or an unstable living arrangement.

“When the case comes up on the court, it is the court’s responsibility to consider the mother and father equally in determining what is best for the children,” White says.

While the court has to stay unbiased in terms of gender, parents can go into custody battles with their own bias on who has the best chance of getting custody. Cordell & Cordell CEO Scott Trout, whose law firm with offices in 34 states specializes in representing fathers, says fathers can go into the dispute feeling cornered.

“[Fathers] settle for minimum custody because they think it’s all they can get,” Trout says. “Pessimistic attorneys will tell their clients that it may be the best deal on the table.”

Kaminsky says his father has expressed that this was a concern in the past. His father (who did not want to comment) has said that courts do favor the mom in custody battles.

“I was younger when all of this happened,” Kaminsky says. “But hearing about it now that I am older, I do feel bad for my dad and that he felt that way.”

When either parent feels victimized by the other, they can make exaggerations and lies for a better case, according to guardian ad litem (GAL) Timothy Carlson.

During a combative custody disagreement, a GAL may be requested by the parents or appointed by the court. When appointed, a GAL is tasked with representing the best interest of the child. They question the kids, the parents, and anyone else who could give insight to the case, in order to give the court a basis of information for what would be best for the children.

Carlson says it is not uncommon to have parents feed their children lies in order to make the other parent look bad and decrease their chance of custody. It is his job to find out what the truth is through the questioning process.

“Parents [can] use their children as weapons in a divorce,” Carlson says. “When that happens I get appointed to be an independent third party to get what the parents are trying to do. I try to get them to stop this behavior and show them that it is harming the children.”

Carlson has also experienced cases where the mother will think she has a better chance of getting custody solely because she is the mother. This is based on an old stereotype of parenting roles.

“In a custody case, it is the court’s responsibility to consider the mother and father equally in determining what is best for the children,” —Maury White, Domestic Relations Lawyer

“[Mothers] feel that, based on an old-time bias, the courts are going to always find that the children are better off with her when that is not necessarily the case,” Carlson says. “Traditional roles have changed through the years. There aren’t really family units made up of a stay-at-home mother and a father who works [anymore], there are two working parents.”

The roles of parents have been changing every decade. Compared to the 2.5 hours a week fathers spent on childcare in 1965, in 2011 fathers now spend upwards of seven hours a week on childcare, according to the Pew Research Center. Mothers spend 21 hours per week in the workforce in 2011, compared to the eight hours a week in 1965.

As parental roles continue to converge for both parents, the decision of custody doesn’t lean toward the mother in the courts. Throughout the 1900s, the mother would have the benefit of the doubt in a custody battle due to the fact that she spent the majority of the time with the kids.

However, before 1900, the mother was not entitled to custody and only the father could get custody because women had no legal rights. University of Akron Chair of Constitutional Law Tracy Thomas says the law changed and it was said that for young children under the age of six, mothers would be the “better parent because they were more nurturing.”

“Studies also show that fathers did not request custody,” Thomas says. “It was still a more classic setup where the mother stayed home and cared for the children and the father worked. So the father would continue his job and the mother was the one who had the time and the ability to take care of the children.”

The more likely outcome of a custody battle in today’s modern-era is shared custody. Thomas says shared custody is the preferred outcome, because then the child will still have adequate time with both parents.

“[Shared custody] is not always 50-50, but it means both parents are involved somehow,” Thomas says. “They don’t have to have equal or shared living but they both deal with decision making, and care of the children.”

According to Thomas there are five factors that go into a custody decision: the wishes of the parents, wishes of the child, the child’s adjustment to school and the environment, the child’s interaction with other people, friends, siblings, step-parents, and finally the health of everyone’s mental and physical health.

With these factors in mind, the decision was made to give Kaminsky’s parents equal custody. Kaminsky says he likes the equal custody that his parents have because he can see both of them. Though Kaminsky likes the custody agreement he says the scheduling can get “clunky.” Switched so often between houses can make it easy to leave things at the other parent’s house and then he has to go without those items until he sees the other parent again.

“I grew up with them always being apart,” Kaminsky says. “I got used to always switching between houses.”