Story and Photography by Emma Stiefel

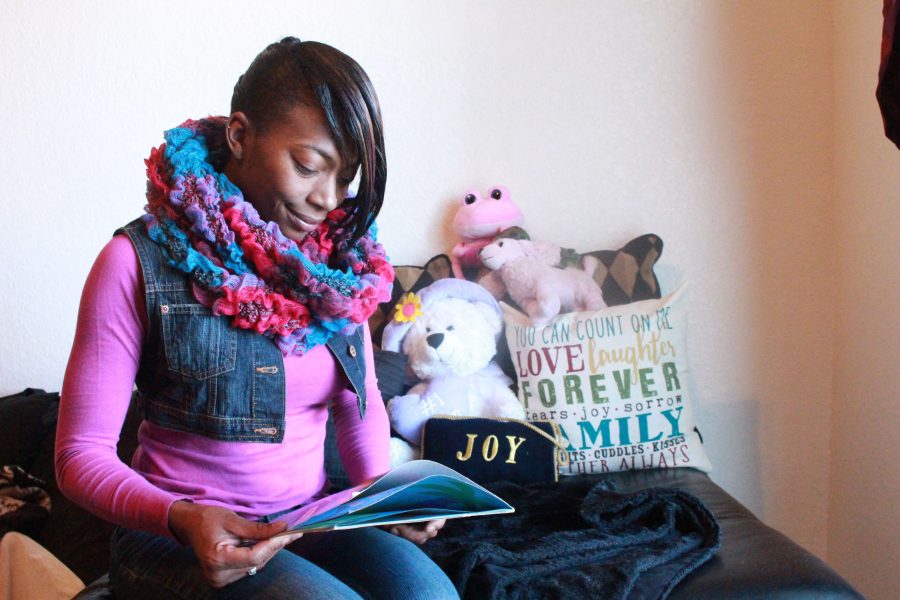

“In the light of the moon a little egg lay on a leaf,” there’s a pause and the sound of a page being flipped to reveal a picture of a dark green caterpillar. “One Sunday morning the warm sun came up…”

Mary King’s voice carried on as her daughter, Kyara King, listened, until the tale of “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” ended. It wasn’t her first time reading the story, and it wouldn’t be her last; the book was one of Kyara’s favorites, and she frequently requested it during their nightly reading sessions.

This time was sacred to Mary. She had always understood the value of education, a point reinforced by the parenting classes she started taking after she gave birth to Kyara. Mary took these courses through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, which helps mothers like her buy healthy food for their family and dispenses advice about meal preparation, budgeting, homeownership and child literacy.

Mary took as many of these types of classes as she could and used any other service available to her. She was eager to do anything that could make things better for her family, which she often struggled to support as its sole breadwinner because her husband was unable to work.

She always sensed that her daughter was bright, for example, so at the age of three Kyara was enrolled in preschool and Head Start, an early childhood program for families who are the most at risk in their community.

“I’ve always known that my daughter is special,” Mary said. “Of course every parent thinks their kid is special. But my daughter was awesome!”

Mary’s premonition was soon fulfilled when their roles reversed, and Kyara started reading to her. Years later, when Kyara was about 12, she was still reading, but her audience had changed.

Now she was taking care of her little brother while her mom was out of the house working two, and sometimes three, jobs as a nurse to provide for her family. Kyara didn’t like taking care of another child when she was still a kid herself; it was “weird and not very fun.” But she still did, because her mom couldn’t and there was no one else to; her parents got a divorce in 2012 (Mary had the exact date, Sept. 14, memorized) and had been separated for three years before that.

Mary would stay for dinner, but after that it was Kyara who had to help her brother finish his homework and get ready for bed. She would make sure that he took a shower, brushed his teeth, and put his pajamas on, and then she read to him until he fell asleep, just like her mother did to her when she was little.

This is only a small part of the Kings’ story, but parts of it may already seem out of place in Lakota, according to several local professionals who work closely with low income families.

Though Kyara, now a senior at Lakota East, is one of the approximately 21 percent of students who are economically disadvantaged in the district, according to 2015-16 Ohio Department of Education (ODE) data, many community members see Lakota as overwhelmingly composed of wealthy and middle class families.

This perception was more accurate in the 2005-06 school year, when eight percent of Lakota students were economically disadvantaged. Since then, however, 1,781 economically disadvantaged students have been added to the district for a total of 3,140, according to ODE data.

Lakota is still much wealthier than many other districts. Of the Greater Miami Conference members, for example, only Mason and Sycamore have less economically disadvantaged students, and Oak Hills has almost the same percentage; the other five member districts all have at least twice as many economically disadvantaged students, according to 2015-16 ODE report card data.

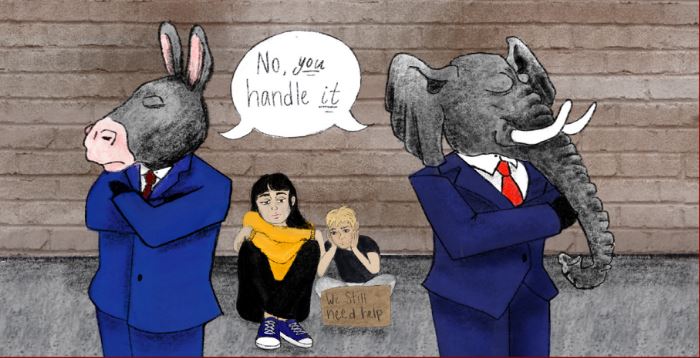

Many, however, believe that there are very few low income families in Lakota, when in fact one in every five students is economically disadvantaged. A Spark survey found that about 40 percent of 182 East students surveyed underestimated the amount of economically disadvantaged students in Lakota by at least 10 percent.

Lakota Community Liaison Jennifer Tye has observed first-hand that “there is a disconnect between what the perception is and what’s reality.” She lives in the area and has a student in the district, and when she tells people what she does for her job “their normal reaction is, ‘you do?’ or, ‘in Lakota?’”

“It never ceases to amaze me that after 23 years of me being here, there’s still people who think that there’s no one who needs help in our district,” Reach Out Lakota CEO/Executive Director Lourdes Ward told Spark. “And they assume that [people receiving help] are sitting at home on their couch just collecting public assistance.”

Most of the people Reach Out Lakota serves, according to Ward, are similar to Mary; they have jobs and are “trying to support a family on a retail or food establishment hourly wage, but it’s just not enough.” Low income families in Lakota, however, occupy a wide spectrum of need.

Ward has seen individuals from wealthier neighborhoods come in for help because their income dropped after a divorce, and other people may only need assistance around the holidays or if an accident prevents them from working. On the other hand, there are about 80 families in Lakota who are homeless and live in a hotel, with another family or in a shelter, according to 2015-16 ODE data.

“Our community would be surprised to find out the amount of need that really does exist,” Lakota Community Liaison Kim Huston said. “And they would be surprised at some of the actual struggles that families are having with paying rent and not having a vehicle and skipping meals because they don’t have enough money for food.”

The rising amount of low income students in Lakota is part of a nationwide increase in suburban poverty. According to Brookings Institute fellows Elizabeth Kneebone and Alan Berube, “suburbia is now home to the largest and fastest growing poor population in the country.”

“The majority reason [for the shift] is people just becoming poor in place, especially after the tech boom in the late 90s and the Great Recession,” Brookings Institute Associate Fellow Natalie Holmes, who works with Kneebone and Berube, told Spark. “It’s not so much people moving to places but people already living there seeing their income fall.”

While it may not be the main cause of the increase in suburban poverty, low income families moving out of cities has also contributed to the trend.

“The suburbs started in the 1950s and have always been a haven for folks who are a little more affluentl,” University of Cincinnati Assistant Professor of Social Work James Canfield told Spark. “But what we’ve seen now is people wanting to move back to the cities because the jobs are in the cities and those types of things.”

As wealthier people have moved back to cities and downtown areas have gentrified, many low income families have been forced, according to Holmes, “to go farther and farther out of the cities” to obtain affordable housing. Lakota is relatively far away from the nearest cities, Cincinnati and Dayton, and most houses in the region are newer and more expensive, so this trend applies more to “inner-ring” suburbs close to cities than the district.

But families may still move here from cities in search of better schools or other benefits. Huston, for example, has noticed that a lot of the students she works with came to the district from Cincinnati, Hamilton or other more urban areas.

“Parents are coming to Lakota because they want their children to have a good Lakota education,” Huston said. “But when they arrive in Lakota they don’t always have the resources they need, because rent is a little more expensive here than it is in some of those areas.”

This is what the Kings did. When Kyara was in third grade, they lived in Cincinnati, where she attended Cincinnati Public Schools (CPS). The family relocated to the suburbs because the neighborhood they moved from, as Kyara remembers, “was actually the number one neighborhood you should not live in, because it was very dangerous.”

The street they lived on was called Hawaiian Terrace, but it wasn’t anything like the island paradise its name evokes. Though it had been relatively quiet the first few years that they lived there, and their neighbors were friendly, eventually the area was plagued with drugs and gang violence.

Mary started talking to her husband about moving, insisting that the family had to do something, had to go. They complained to the landlord about the crime and asked if there were any other properties available in different areas. She was afraid to leave the house, and her children didn’t like playing outside. It was when they were inside, however, that the incident that accelerated the family’s exodus occurred.

Kyara was in her room, maybe playing or reading, when she looked out the window, gazing at the grey asphalt parking lot and the row of townhouses behind her own. Another resident was slowly driving below, inching his trash, piled on top of his car, toward the dumpster.

It was a routine pilgrimage for the residents, who didn’t like carrying garbage on foot. It was something Kyara had seen many times before. This, however, was the wrong moment for her to peek outside.

She watched as the driver was shot. She watched as two men ran up to his car. She watched as they threw his body and then his trash on the ground, before either could reach their destination. She watched as the criminals drove away in her neighbor’s car. And she watched, for a second, as he lay bleeding on the ground.

Then she ran, terrified, to find her mother and tell her that the man “didn’t look ok.” Kyara didn’t really understand what she had witnessed at the time; she was less than ten years old.

That night she saw the man again, on the news, and the family went to stay with one of Kyara’s grandmothers, who lived nearby. In a couple of months, they would be in Lakota.

Out in the suburbs, the Kings finally felt safe. It took Kyara a while to get used to living in a place where “you don’t hear gunshots and no one’s getting robbed,” but once she did, she looked forward to going outside instead of fearing it.

At first, Kyara struggled to make friends in Lakota because she wasn’t used to the way her new peers talked and acted, and “little kids just tell the truth and they’re super rude about it, so everyone said, ‘you sound weird so we don’t want to be friends with you.’” Eventually, however, she met the people she’s still friends with today.

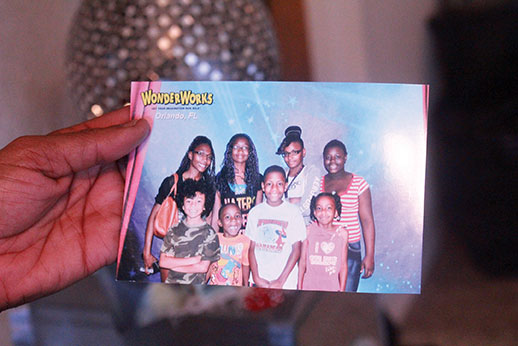

In school, Kyara now had opportunities to do things like travel to Disney World with the East choir, which she loved and would do “ten times over rather than going with my actual family.” She had started participating in choir in middle school, and it became a way for her to escape her stressful situation.

She also found an environment that matched her focus on academics. At CPS, her teachers had noticed that she had a new book in her hands every day and put her in class with students a grade ahead of her. When she came to Lakota, she was on track to take classes with other students her age.

Mary remembered that, when Kyara went to CPS, she would come home and complain about being bored. After the family moved, however, she would complain that “‘oh man, I’ve got a lot of homework,’ but she loved it.”

Despite the increase in economically disadvantaged suburban families, many services for low income individuals remain geared toward urban populations, and suburbs are still designed more for those with means than without.

One challenge for low income families in Lakota specifically is finding affordable housing; Huston, for example, works with families that “literally have difficulty paying rent each month.”

The Kings were financially able to move into Lakota because Mary became eligible for the federal Section 8 housing choice voucher program, which assists low income families with affording “decent, safe, and sanitary housing in the private market,” according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s website.

Once the paperwork for her Section 8 voucher was finalized, Mary again asked her landlord about moving to a different location and found out that they had just bought the Lakota Pointe housing complex across the street from Woodland Elementary.

The first question she had was, “what’s the school district?” When she found out it was Lakota, she knew it had to be a good sign; the family relocated within a week.

Once families like the Kings do obtain affordable housing, however, their challenge often becomes leaving their home. One of the biggest differences between suburban and urban areas is physical access to resources; suburbs, which often lack public transportation, can be extremely difficult to navigate for people who can’t afford a car.

“Transportation is a huge need, not just busing for high schoolers but in general,” Huston said. “We have a lot of families that don’t have a car or rely on other people. I have several families just this past week that I have driven to places, because they don’t have their own vehicle.”

Though they owned a car when they first moved to Lakota, neither Kyara nor Mary currently have their own means of transportation. Kyara has to “catch rides from literally everyone” to get to her part-time job at The Web entertainment center and rides to school with another senior.

Mary lost her car after an accident, leaving her “stuck between a rock and a hard place.” If she wants to go to the grocery store she has to find someone willing to drive her or take an Uber or cab. She tried taking an Uber to and from work for a while, but realized that doing so resulted in “so much going out and not enough coming back in.” Unable to get to her job, therefore, she resigned so that she could eventually be rehired and has been trying to get another car.

For other families in Lakota, not having a car may prevent them from getting the services they need; according to Ward, “living out in West Chester, there’s a lot of agencies that are not here, and you would have to go to downtown Hamilton to apply for things [from them].”

Recently retired Mason Police Officer Derek Bauman, who is also the Vice Chair of All Aboard Ohio, a group that advocates for more public transit in the state, observed that low income families that do have a car are often still unable to afford repairs or speeding tickets.

Throughout his career as a police officer, Bauman saw how devastating a $150 speeding ticket, no more than “a nuisance” for more affluent people, can be for low income families. Many won’t go to court or pay such a fine because doing so would mean not being able to pay for gas, electricity, food and other necessities.

“So they just ignore it,” Bauman told Spark. “And what ends up happening is they get a warrant issued for their arrest for their failure to appear in court. Then they get their driver’s license suspended.”

Once that happens, an individual can be pulled over again for driving without a license and get an even more expensive fine or have to spend at least a day in jail. If they do get their license reinstated, they have to go to a Department of Motor Vehicles office and pay another fee they likely can’t afford, leaving them, according to Bauman, “in the [criminal justice] system and without a driver’s license.”

Nevertheless, many people in such a situation continue to drive to get to work or buy food, until “they get pulled over again, and what happens is it starts to snowball.” Bauman has seen people caught in such disastrous circumstances “simply break down” from stress.

“If you don’t have help, you’re screwed,” Bauman said. “In our society that is so car dependent, I don’t know what you do. You keep driving and you keep getting pulled over and getting all these fines, and it’s a horrible problem because people get into that cycle and have a hard time getting out.”

In short, according to Bauman, “the things that are merely an inconvenience to those with more means could be devastating to somebody with a lower income,” a concept that applies to all realms of life, not just transportation.

Huston has seen the families she works with become victims of this “snowball effect, where one bad thing happens and then it starts another bad thing and another bad thing, and it makes it really hard for them to get out of that rut.”

The Kings have been in similar situations, where a single problem has an oversized effect on their lives. In 2012, for example, Mary had a hysterectomy to remove fibroid tumors from her ovaries, and in 2013 she had another operation to fix her temporomandibular joint dislocation, which would cause her jaw to lock open.

She continued to work two jobs while suffering from the effects of her fibroid tumors: they would rupture, causing her to menstruate for an entire month and disrupting her blood pressure. Eventually, however, Mary was laid off because she had gone to the hospital too many times.

Then the Kings were evicted from their home because, as Kyara remembered, “when you’re living in an apartment and you have to pay rent, they don’t really care.” Mary didn’t have a Section 8 voucher anymore, so they couldn’t afford market rent in West Chester or Liberty Township. The family was homeless.

Mary reached out to the community liaison she was most familiar with and learned about St. Raphael’s, a shelter in Hamilton that provides families with fully furnished apartments.

They didn’t stay long, no more than three months; Mary had resolved that “if I just get some help for 90 days, I can do it.” The staff at St. Raphael’s made sure that she went to doctor’s appointments, took her medicine and got enough sleep. Once she was healthy enough to work, Mary was required to turn in five job applications a day until she got hired.

Though they had moved out of the district, Kyara and her brother continued to attend school in Lakota. Under the federal McKinney-Vento Act, according to Lakota Director of Federal Programs Kim McGowan, districts are required to transport homeless children to and from their “school of origin.” Kyara had to wake up very early in the morning to leave in time for the 25 minute drive from the shelter to Hopewell Junior, where she was in eighth grade.

The family moved back into Lakota and was stable until 2014, when Mary lost her job again. She had been taking care of an elderly couple, and when the husband died the family decided to move his wife into a hospice, taking away the first job that had paid her enough to support her family.

“Yeah, it’s always something,” she sighed wistfully while recalling the memory. Being laid off had caused her to become depressed, and she felt “totally defeated.”

“Here I was, with a really great job, financially set,” Mary said. “We were taking family vacations, I was putting away for my daughter’s car, mommy was doing it all. [Losing that] just felt so overwhelming.”

The Kings lived off Mary’s savings and what she could borrow from her retirement plan until they became homeless once more. At this point, however, Mary’s relationship with her ex-husband was less hostile, so Kyara and her brother stayed with him while she was working, getting counseling, and “doing her own thing to get back on her feet.”

Financial challenges like those faced by the Kings can create “non-cognitive barriers to learning,” as community liaisons call them, for economically disadvantaged students. For example, according to Tye, a student could be “bothered or not learning in the classroom because they’re hungry, they’re worrying about mom or dad, they’re not sure where they’re going to lay their head that night, or they can’t get medical care.”

East Principal Suzanna Davis stressed that individual students’ circumstances differ, but noted that poverty can be “all-encompassing for some students.”

“It’s an additional layer that students bring to school with them everyday,” Davis said. “It certainly can have an effect on every aspect of their life, whether it be relationships, academics or extracurriculars.”

The cumulative effect of obstacles like these on an economically disadvantaged student’s academic performance can be severe. Tye sometimes worries that a student she’s working with won’t graduate, “not because they aren’t smart enough, but because there are so many obstacles being thrown in their way.”

About 80 percent of economically disadvantaged Lakota seniors in the class of 2015 graduated in four years, compared to more than 95 percent of non-disadvantaged students, according to ODE data. And economically disadvantaged Lakota students in the class of 2016 were about half as likely to earn an advanced score on an Ohio Graduation Test than their wealthier counterparts.

Lakota Board of Education member Ray Murray told Spark that this achievement gap appears early in elementary school because, for example, a child whose parents couldn’t afford to send them to preschool or stay home with them may often have a smaller vocabulary than a more fortunate one.

“It just progresses, because these kids that are on target continue to learn more, but the kid who started so far behind the line will be trying to catch up,” Murray told Spark. “But it really is hard to catch up, and that gap is going to still be there. That’s what Lakota is struggling with.”

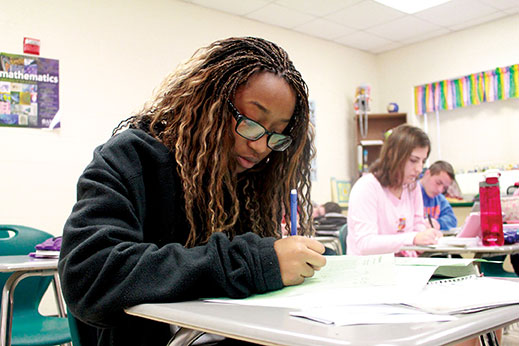

Though this trend is prevalent, individual students can overcome their financial difficulties and succeed in school. Despite her hardships, Kyara has been able to remain focused on academics and has consistently made the high honor roll.

“Academically, she’s always excelled,” Mary said. “I really can’t remember a time when she got a D. If she did, I don’t know about it, that one got past me.”

After she moved in with her dad during her junior year, however, Kyara’s grades began to fall. Because she had been very independent when her mom was at work, she “wasn’t quite used to having a parent” and would “always butt heads” with her dad; their conflicts affected her first and second quarter grades, and she got her first C on a report card.

Kyara and her dad had “a huge fight this one day and he was like, in more colorful words, ‘you need to leave.’” She realized that “just because I’m going through something doesn’t mean I need to slack off, especially this year when it’s really important,” and moved in with a friend; her grades subsequently improved.

She’s currently enrolled at East as an independent student, meaning that she is legally able to make decisions for herself. Since the beginning of this year she’s been living with another friend and has had to budget the salary she receives from working four days a week at The Web to pay for her phone bill, eating out, toiletries, school supplies, clothes, shoes and anything else she might need.

Her brother is still staying with their dad, who now lives in Middletown, though Mary is currently “going through the courts to switch everything back,” another reason she hasn’t been able to work.

Community liaisons like Huston and Tye are normally able to help students like Kyara and her brother get the resources they need to be academically successful. When King needed to get a vaccine required for all seniors but couldn’t because she didn’t know where her mom was, for example, Tye helped her get the shot so that she could attend school in the fall.

The community liaisons are employed by the Butler County Success Program but contracted to work in Lakota and other districts. In Lakota, 444 students participate in the Butler County Success Program, all of which are at 200 percent of the federal poverty level or lower. Tye, who works with high schoolers and middle schoolers on the East side of the district, currently has a caseload of about 60 students, and Huston, who works with the same age group on the West side, has a caseload of about 90.

Students normally begin working with a community liaison once they are identified as potentially needing additional services by a Lakota staff member or someone from outside the district such as a church volunteer. A teacher may notice, for example, that a student is squinting because they don’t have glasses, or a cafeteria worker could see that they don’t have any money in their lunch account.

Once they’re referred to a student, the community liaison will contact their parents. The program is voluntary, so, according to Tye, “there are definitely families that I reach out to but don’t work with.” If they’re able to reach the parent, however, a community liaison will set up a meeting to find out the broader reasons for why the student was referred to them.

“For example, a child can be referred by a teacher saying, ‘this boy doesn’t have glasses,’” Huston said. “But then when we get to the home and meet the parent we find out that they don’t have insurance and that’s because mom lost the job and now mom also can’t pay rent, so there’s a lot more to it beyond what the teacher realized.”

After that initial meeting, a community liaison will work with a family throughout the school year to ensure that all their needs are met. They can connect families with a wide range of resources, including assistance for paying utility fees, mental health counseling and organizations that provide food and school supplies.

“This community is extremely generous, and I actually usually don’t go without,” Tye said. “If a family needs something, I can usually find it.”

In her office at Ridge Junior, for example, Huston has a drawer full of items that staff members have dropped off, including clothing, athletic shoes, gift cards and a bag of bright orange body wash, and she also had a few teachers help a student go on a class trip to Washington, D.C. Tye has a similar stash of donations in her office.

The Kings found out about the Butler County Success Program at the Lakota Enrollment Center and soon began working with a community liaison, who told them about other resources in the community like the Boys and Girls Club, several churches and family counseling. It was a community liaison who helped them find a place to stay when they became homeless.

“These people were like godsends” Mary said. “I’m really glad that they are affiliated with the school so closely, because I didn’t know who to call or what I would do if anything happened.”

While the availability of resources in Lakota means that she’s normally able to meet the physical needs of her families, Tye wants people to be “more open minded and kind toward people that are different.”

“I wish the community as a whole would be a little bit more understanding that there are families and students all around them that need help,” Tye said. “And it’s not because they’re lazy or they don’t care. There’s some real tough stuff that students in this school go through.”

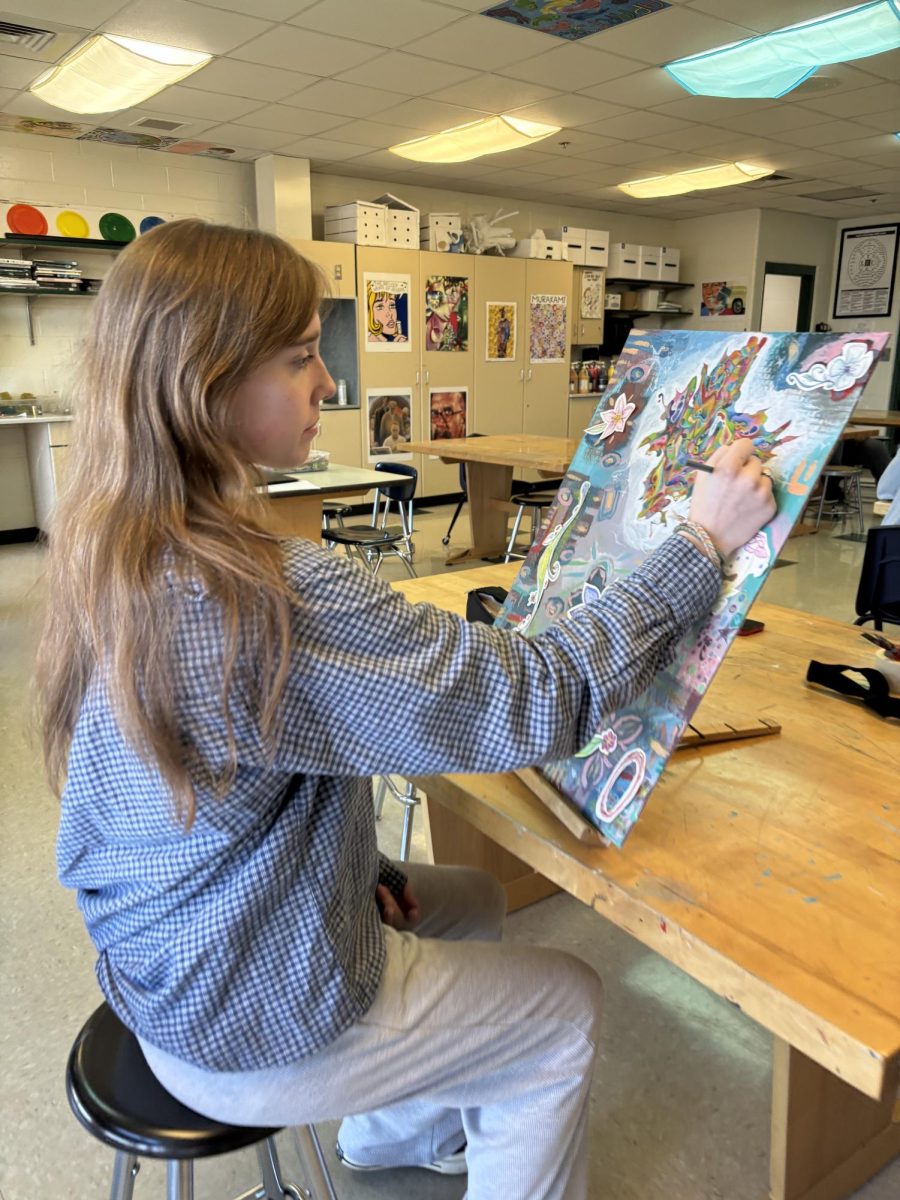

One way a change in understanding could be accomplished is through Lakota’s Champions for Change program, which was started this school year to help the district adapt to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse student body and make sure the community is welcoming to all families.

“A lot of what we do is working on mindset, so concepts that can be applied in any way or to whoever,” Lakota Diversity Consultant Dr. Monique Johnson, one of the leaders of the program, told Spark. “[For example,] we talk about unconscious bias, and that applies to a variety of different populations. It’s not just race; it applies to gender, body weight, students in poverty. It could be anything.”

Though Kyara hasn’t been stereotyped like this in school, she remembered overhearing offensive comments from other students at her work and was shocked “just to hear the back and forth banter and what they would say about other people.”

Mary knows that “being a low income family in Lakota comes with its own struggles as far as status,” and she was initially hesitant about her family being featured in this article because of how it might change the way others treat Kyara.

There have been times when she’s felt like she’s been judged or ostracized because of the stigma associated with being a low income single mother, especially since she is younger than many other parents with children in high school (she was 15 when she had Kyara). Mary remembered getting invitations to social gatherings when she had a better paying job or a new car, but said that if she fell on hard times again, she’d stop receiving phone calls or “hellos” at a choir concert.

“I wish things were different, but this is life,” Mary said. “I just stay as positive as I can and teach my children to treat others kindly no matter what they have or what they don’t have.”

She seems to have succeeded. Mary and Kyara’s personalities show no traces of the hardships they’ve been through; instead, they’re both incredibly positive and optimistic about the future.

Mary hopes to work as a nurse again soon. She’s more excited, however, about her plans to open up a storefront, because “as long as I’ve been in West Chester there has never been a beauty supplies store, and I’m not talking about Sally’s.”

People are always asking her where she gets her hair products, so she’s decided that it’s time for her to “make her move” and become an entrepreneur. In addition to beauty products, she plans on selling both East and West spirit wear so that she can attract customers from all over the district.

Once she’s financially stable, she plans on giving back to the community with her family. They haven’t been able to do it in two years, but the Kings “have a charity, that we thought of on our own, called Santa’s Little Helpers.” During the holiday season she would collect purses and fill them with personal hygiene items, and on Christmas, before any presents were opened, the family would pass them out at a homeless shelter.

Though Kyara originally wanted to take a gap year after graduation, her counselor convinced her to go straight to college, and she’s currently in the process of applying to Wright State University, the University of Cincinnati and Berea College. She’s determined to be the first person in her family to attend a four-year university, the first person able to say, “‘this is possible. I went through craziness, and I’m still able to get this done.’”

Kyara plans on going into social work, following her family’s tradition of helping people: most of her relatives, including her mother, went to nursing school or joined the military. While Kyara doesn’t think she is “strong enough mentally or physically to do that,” she wants to be able to “reach out to the kids that are like me.”

Now, she would advise other students facing similar challenges to “find your little happy bubble,” like choir is for her, “and stay in that happy bubble or else it’s not going to be fun.” Even if a situation “seems super hard,” she said, “it is very doable, you just have to be able to ask for help.”

Beyond school and careers, Kyara is certain that marriage is in her future. Until recently, however, she didn’t want children; she thought that “I wouldn’t want to put anyone else through what I went through.”

Now she’s less sure. If she can “really pull this off” and go to college, then “that changes the whole story.” Maybe she still won’t have kids. But maybe she will, or maybe she’ll adopt, and if so, though it’s cliche, she wants to give her children what she never had: “money saved up for college and everything else.”

Perhaps Kyara will become a college graduate with a job she cares about, raising children in a home devoid of financial hardships but carrying on her family’s bedtime reading tradition. She might, one day, even share her favorite childhood story about a caterpillar with them and echo the concluding line her mother read to her all those years ago: “he nibbled a hole in the cocoon, pushed his way out and… he was a beautiful butterfly!”

Eric • May 18, 2017 at 10:44 am

I just want to compliment the author of this story. Top-notch work. I loved the way you weaved your reporting of events into your narrative. I will be using this as an example in my own journalism class.

Keep it up.