On Wednesday, May 15, 2024, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine signed into law House Bill 250, after the bill unanimously passed in the House and Senate.

The bill requires every school in the state of Ohio to put a policy in place restricting cell phones by July 1, 2025. This comes before the start of the 2025-26 school year.

The bill states that the policy must address three things: emphasize that student cell phone use should be as limited as possible during school hours, reduce cell phone related distractions in classroom settings, and ensure students can still have access to their phones if defined in their IEP plan or for health reasons.

The bill arose after DeWine expressed concern about phones in schools earlier in the year and encouraged schools to address it. According to Lakota Superintendent Dr. Ashley Whitely, phone usage can hinder overall learning.

“Phones in general, not just in the classroom, are a dichotomy in that they can be both distractions and tools,” Whitely told Spark. “While cell phones certainly have a place in our lives, actively participating in their education should be the focus of our students during the school day.”

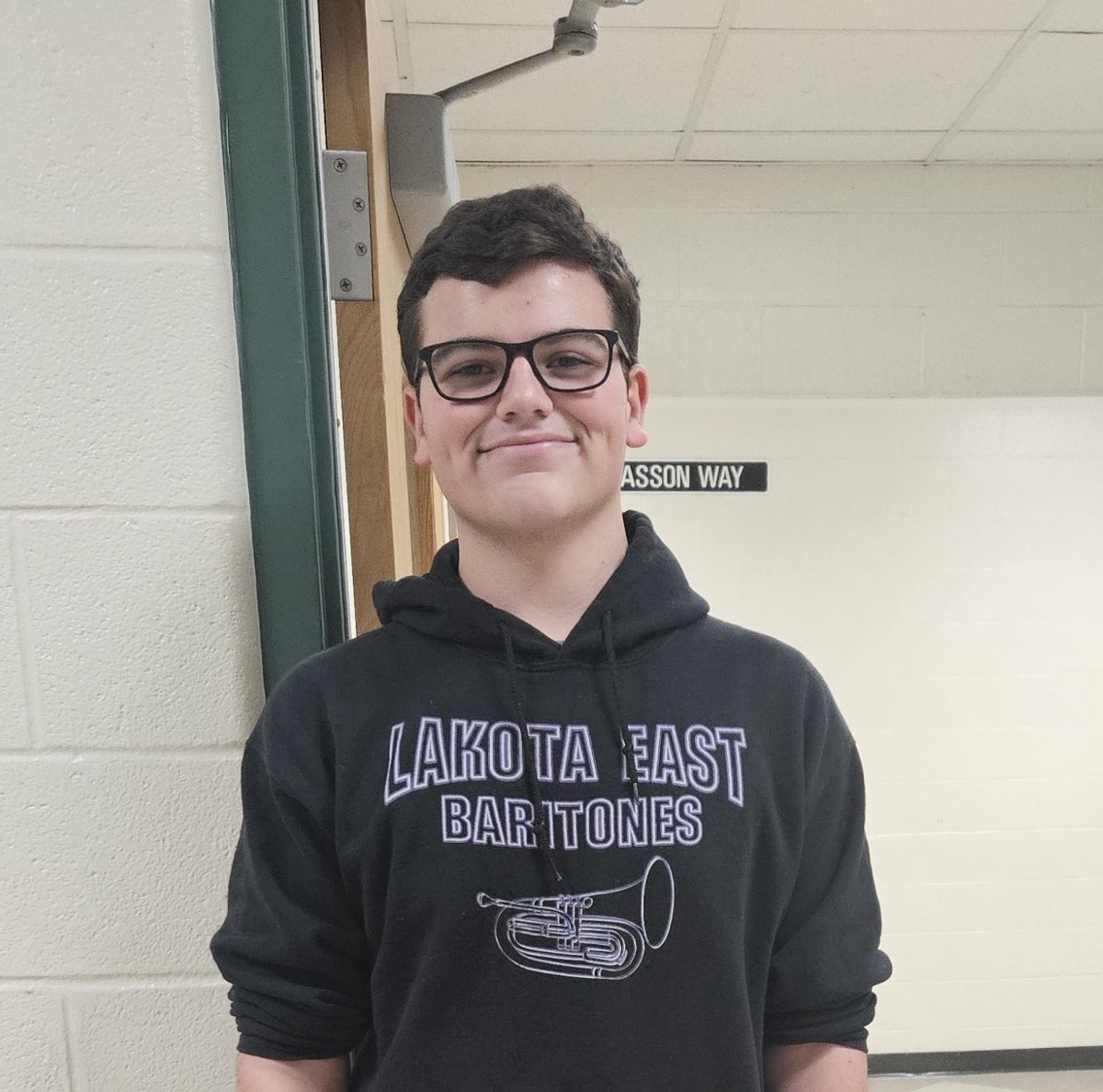

East American Law/Criminal Justice and US History teacher Kyle Vander Horst has seen the issue of phones evolve over his years teaching at East.

“I think it’s just led to a level of disengagement in the classroom when generally kids are sometimes prioritizing their phone over learning,” Vander Horst told Spark. “It just becomes a challenge as a teacher.”

In a Spark survey of over 300 East students, 32.8% agreed or strongly agreed that phones were a distraction from overall learning, 26.8% disagreed or strongly disagreed, while 40.4% were neutral.

East Principal Rob Burnside wants to help students develop the skills and discipline to balance their learning and the distractions that they face.

“Using an analogy to distracted driving, you can’t text while you’re driving, but I can still stream music, I can still use my GPS on my phone,” Burnside told Spark. “That’s an acceptable use of that tool in that form. I think that they’re finding ways to make sure that we do something very similar in the classroom.” Schools all across the state now have to either revise the current policy they have in order to fit new requirements, or draft one from scratch.

Lakota initially adopted the current phone policy in 2013, but it has not been revised since December 2017.

Developing the policy will primarily be handled by Board of Education Policy Committee members Kelley Casper and Doug Horton. The process is made up of two components: the board approved policy itself and administrative guidelines, which determine how the policy is enforced.

“The reason we’re trying hard to not only fix the policy, [but the administrative guidelines as well] they tell you, here’s the consequences,” Casper told Spark. “When we started this process, we had a junior [high school] principal say that I want them to have no phones anywhere, anytime. We also have a junior [junior high school] principal who says I want them to have their phones whenever they want them. So, even within our grade bands we have inconsistency.”

On September 25, the Board of Education held a Community Conversation at the West Freshman Campus to engage with students, staff, and parents about what Lakota should do in regards to their policy.

“I think it’s a good way to reach the community,” said Ellis. “A lot of people come in with their opinion set, but I’m looking forward to hearing from administrators and seeing their opinion.”

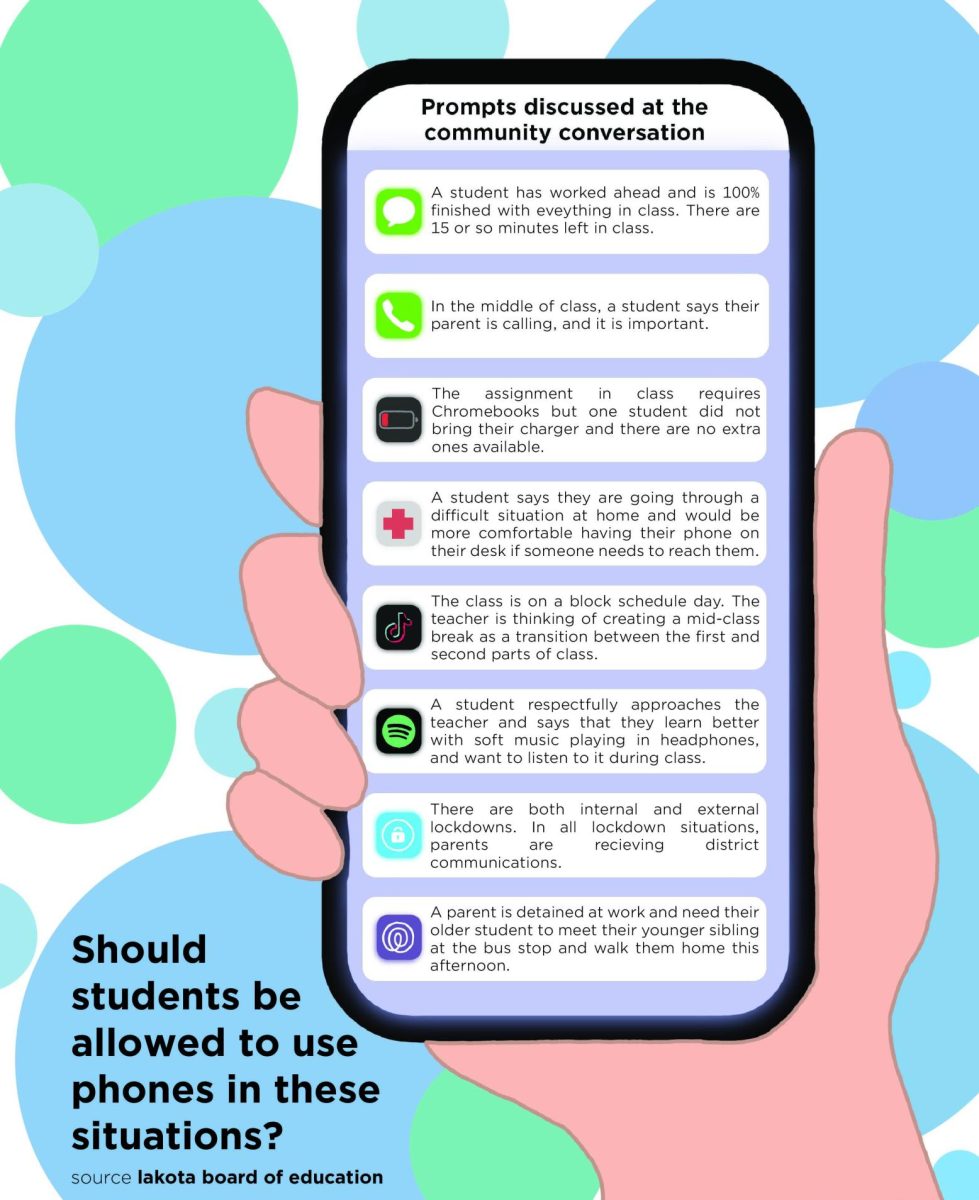

At the Community Conversation people were separated into eight groups. Each group received a prompt that they were given 20 minutes to discuss amongst themselves, they were then asked to share their conclusions with the room. The prompts ranged in situations from lockdowns to music listening, written in a way that provides a gray area as to the solution. This approach was taken in order to analyze the different practices among teachers, according to Horton.

“This is one of those issues that is so personal, how teachers use cell phones in their classrooms, gets into their philosophy of teaching,” Horton told Spark. “We really need to fully understand the issue from all the different viewpoints.”

Community member Amanda Stacy taught at a middle school in North Carolina for over 20 years and is opposed to nearly all technology in the classroom.

“I am a believer that we as the teachers and the parents should be educating people that it’s actually not best for you to be listening to music all day long. You need to be bored, to have your own mind and be able to work in a gorgeous way,” Stacy told Spark. “Of course it’s much easier to not do those things, [but] this is addictive.”

At the beginning of the 2024-25 school year East gave teachers the option to have phone pouches for their classrooms as a result of research found by the district according to Burnside. There was no requirement to use these, as Burnside still wanted to give the power to manage the classroom to the individual teachers.

“You know, not every teacher handles homework policies the same way,” said Burnside. “We wanted to give them permission to manage it in their classrooms, while also giving them tools to manage in a way that fit their style in their classroom.”

According to a Spark survey, 34.9% of students believe that the pouches have helped curb phone usage in class.

Vander Horst believes a district wide policy would clear up confusion and reduce stress for teachers.

“Some teachers have different policies, and that’s fine,” said Vander Horst. “Where some teachers may say, I don’t ever want to see them. It puts a lot on the individual teacher to have to maintain that policy, where in a district wide policy, everybody’s on the same page.”

Teachers have implemented a variety of policies, some of which include pencil pouches on desks, phones face down on the table, and access to phones during individual work time but not during instruction, according to a Spark survey.

The policy implemented by Dublin City Schools states that students may have their phones at school, but they must be powered off during class. Students are permitted to use them at lunch, in between classes, and before and after school. According to the policy, if these rules are broken, staff are required to confiscate the device and bring it to the principal’s office where it must be picked up by a parent. The policy was written in a way where it could be easily suited to many situations according to Dublin City Schools Coordinator of Media Relations, Keyburn Grady.

“We determined that, by maintaining a vague policy, we avoid the need for frequent updates each time a new device or technology emerges,” Grady told Spark. “With the increasing popularity of devices like Apple Watches and other unforeseen technological advancements, this approach allows us to be more adaptive to new technology and student/building needs.”

The principal of Karrer Middle School, Brooke Menduni, has seen a great impact on students since Dublin City Schools banned phones.

“Students grumbled at first, however since it was consistently enforced across all settings, it was something that they soon understood was a part of how we do things, and quickly complied. It has made a huge difference in the amount of interactions and positive relationships students report having at school, their overall sense of belonging, and a decrease in discipline,” Menduni told Spark. “It allows something to ‘come off of student’s plates’ so to speak, regaining their attention to academics and face to face communication/problem solving and other essential skills.”

One of the biggest topics regarding phone policy is student safety. In a Spark survey, 78% of students had concerns about their safety if they did not have access to their phones, while 22% did not have any concerns.

According to Horton, administrators and officials have taken on the responsibility of assuring parents that students are safe during the day.

“I think that’s difficult because that’s places where people don’t naturally want to go, like I don’t want to imagine East on lockdown with my daughter there,” said Horton. “So that is going to be a very tricky issue, and I think we probably need some more work there.”

Burnside taught at East when there were only three phones in the building and believes there are situations where phones could help but overall they are a detriment to safety in lockdown situations.

“[Students] get on the phone and they send a text message [to their parents], and then the parents are freaking out, then you have the parents calling the front office. Now we’re getting 20 phone calls to the front office asking what’s going on, while we’re also trying to figure out what he’s going on ourselves,” said Burnside. “I understand what the concern is, but I think there also would be a lot of instances where it could be a distraction which hinders safety, and it may cause higher instances of stress and anxiety, which can lead to a greater level of disconnect.”

Horton anticipates the new cell phone policy being finished in January or February.

“[We] want them to have time to craft the administrative guidelines and the processes in individual buildings, how they would utilize that, and then roll that expectation out to staff and students and parents,” said Horton.