STORY AND INFOGRAPHIC NATALIE MAZEY

PHOTOGRAPHY RILEY HIGGINS

Donovan Sweeten was thrilled to be taking Honors Chemistry, a class full of experimentation and hands-on learning. When the East junior checked the box to sign up for the class, he had no idea what the next year would bring. A year spent as part of Lakota’s Virtual Learning Option (VLO), meant Sweeten would never learn a staple of chemistry: how to light a bunsen burner.

Sweeten chose to participate in VLO for a multitude of reasons. Two of them were protecting his grandparents from COVID-19, and putting himself in an environment that would better replicate a real life work day. However, after a year of relying solely on technology to learn, he began to regret this decision.

“The negatives outweighed the positives for me personally,” Sweeten told Spark. “The bulk of that revolved around my reliance on technology to do everything, which obviously I knew was going to happen; it’s virtual learning. But I didn’t expect it to be as emotionally taxing as it was.”

Sweeten faced an emotional toll as technology became all-consuming, but, for some, it was a lifesaver. Technology has found an increased presence in the workforce and the school system over the past decade, but the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated its use. According to Telegeography, a telecommunications market research company, the pandemic drove up global internet capacity by 35% between 2019 and 2020. Before the pandemic, the use of technology was a choice, but lockdowns and stay-at-home orders meant technology was the only way to move forward.

Before the pandemic, 1 in 5 people were impacted by a mental health disorder, but this figure has risen to 1 in 4, according to the National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI). Associate Director of NAMI of Butler County Alyssa Louagie worked from home during the pandemic and has had to adapt to provide support for those who need it. This meant turning to digital platforms for support groups and fundraisers.

“Beyond the pandemic itself, what our society has gone through is essentially a giant group trauma,” Louagie told Spark. “The ramifications of that don’t just go away when the virus gets under control.”

NAMI of Butler County began transitioning back to some in-person events in August 2021, but Louagie says they expect to continue to offer online support groups in the future.

“It’s easier for people to get [online] because they don’t have to commute or find transportation,” Louagie says. “But I think that on the flip side, it is sometimes harder to build those connections in the same way that you would in-person.”

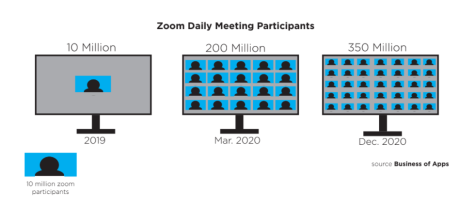

While participating in VLO, Sweeten struggled with finding these connections. Sweeten, like 62% of East students according to a recent Spark survey, felt largely negative about virtual learning. Even though platforms like Zoom grew exponentially, with Zoom grossing $671 million in profit in 2020, compared to $21 million the previous year, Sweeten says he used the platform less than a handful of times throughout the entire school year.

“Not being able to see or physically interact with any of your teachers or peers just took a lot of the motivation away for me to get up at a normal time, start work early, and finish things on a consistent schedule,” Sweeten says. “It became a constant struggle to force myself to work.”

During the pandemic, Lakota mainly utilized Canvas, Seesaw, Zoom, Google, and Microsoft Collaboration Suites, according to Chief Technology Officer Todd Wesley. While these tools will still be utilized, Wesley recognizes there needs to be a balance with technology in the classroom.

During the pandemic, Lakota mainly utilized Canvas, Seesaw, Zoom, Google, and Microsoft Collaboration Suites, according to Chief Technology Officer Todd Wesley. While these tools will still be utilized, Wesley recognizes there needs to be a balance with technology in the classroom.

“As a district, we promote the purposeful integration of technology to support learning in each course,” Wesley told Spark. “No one wants to be on a computer all day, as shown by the findings in multiple studies during the lockdown. Balanced learning, as determined by the teacher, along with student voice, is the sweet spot.”

In a Spark survey, 72% of students prefer using pencil and paper, yet 94% of students say that their technology use increased during the pandemic.

For some, physical interaction does not feel necessary in the school or work day. Translation recruiter for ZOO Digital Vicki Dick, a provider of subtitling, dubbing, and media localization services, says she and her team work completely remote.

“[ZOO Digital] got a lot bigger [during the pandemic]. We grew by 100 employees in a year,” Dick told Spark. “Everybody needed what we had to offer. I had a much better ability to adapt because I had already been working from home, and the company I was working for was only growing.”

Dick works solely from her laptop, but that means she has the ability to work from anywhere, whether that be in the car before picking her kids up from school or anywhere in her home. Access to technology has led ZOO Digital to hire associates from across the globe without compromising productivity.

“[ZOO Digital] has online resources that anybody from around the world can gain access to,” Dick says. “They understand that everybody’s in different time zones so that they need to be a 24-7 company.”

Unlike ZOO Digital, Paymo, a platform for online work management software, found that working remotely was not best for the growth of the company. Chief Marketing Officer of Laurentiu Bancu says that Paymo is able to help other companies work remotely. With features like time tracking, team scheduling, and invoicing, the platform lends itself to aid companies who work in-person or remotely.

“Overall, to be honest, we’ve noticed a decrease in productivity and efficiency [when online], and we were among the first in our region to return to the office,” Bancu told Spark. “We believe that remote work and collaboration are not for everyone, and it takes time until an organization can master this situation.”

Head of Brand and Content for Hive, a productivity platform for centralized workflow management and insights, Michaela Rollings works remotely from Florida, However, the Hive team is a hybrid organization with some employees inhabiting coworking spaces in New York City and others fully remote. This situation has lended the brand this ability to innovate new technologies that will make life easier for other companies working remotely.

“As much as we’re community driven, we’re also heavily influenced as a product by our ways of working internally. That’s actually how Hive Notes, an app integrated with Zoom, came to be,” Rollings says. “We realized that we were taking part in so many more remote meetings, and we needed a way to keep track of notes and next steps, so Hive Notes was born.”

Starting in the 2021-2022 school year, 1:1 technology, like providing chromebooks to all students, has expanded down to third grade. K-2 students have a ratio of about 2:1, meaning two students per every chromebook or other technology, technology in Lakota.

“[1:1 technology] provided a great foundation to continue to build on once the world locked down,” Wesley says. “We subsequently returned to school last year with almost 25% of our students online in our VLO program, and then our return this year with around 2% of our students online.”

For Sweeten, returning back to in-person learning felt like a much-needed next step.

“The way I view social interactions was severely damaged by the fact that I was surrounded by technology,” Sweeten says. “When you’re at home, the only social interaction you get is through the entertainment you watch. You start to view those conversations, those person-to-person interactions, as solely entertainment, where you do not have to participate. And when you do that for an extended period, and then you’re thrust back into normal functioning society, it’s very jarring.”