Story by Samadhi Marapane | Photography Used with Permission

Her birthplace has always been Veracruz, Mexico. Yet, when Xavier University junior Heyra Avila was four-years-old, she moved to the United States (U.S.) with her parents, as they looked for jobs and sought to flee the poverty in Mexico.

“[My parents] saw that there were more opportunities here and a better life than we could ever imagine in Mexico,” Avila says. “We were really poor, we didn’t have food, running water [or] a stable roof over our heads. Sometimes, [our roof] would fly off with the wind.”

In her junior year of high school, Avila decided to apply for consideration for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), in attempts to remain in the U.S. to continue her education and work. Now, halfway done with her time at Xavier University, DACA has allowed Avila to work as an interpreter at a law firm.

According to the American Immigration Council, DACA is a work authorization for certain young undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children. With this, DACA has enabled almost 800,000 young adults to work lawfully, attend school and plan their lives without the constant threat of deportation.

DACA was an executive action issued by former president Barack Obama in 2012, initially meant as a temporary solution. This temporary residential status must be renewed every two years with a $465 fee and specific eligibility requirements. In a recent Spark survey, 39 out of 392 East students believed that they are very knowledgeable of DACA, 87 believe only somewhat and 266 believe that they are not knowledgeable of DACA.

“When I applied for DACA, the first thing I thought of was ‘what am I going to do when it ends?’ I knew from the beginning that it wasn’t going to last forever,” Avila says. “It was only meant to be a temporary solution and a push for Congress to pass legislation that would allow us to stay in the country we’ve known all our lives.”

However, under the current Trump administration, Avila says DACA is “winding down” and opportunities are in the process of phasing away for not just her but other people too. About 690,000 unauthorized immigrants were enrolled in DACA as of Sept. 4, 2017, according to a 2017 Pew Research Center study.

Due to federal court orders, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is not accepting requests from individuals who have never been granted deferred action under DACA prior to Sept. 2017. Because of this, Avila says there is an ongoing fight from activist and the community to get DACA recipients a more tangible solution that’s more inclusive.

“Many immigration laws in the U.S. are outdated and unjust. Simple as that,” Avila says. “However, starting to unravel exactly how and why opens up a can of worms and a very complex issue that spans back decades and decades.”

According to the Undocumented Students program at University of California, Berkeley, DACA protects youths from deportation and provides them with a work permit and attend schooling. However, Avila says though DACA intends to protect these youths, it hasn’t been that way for everyone.

All undocumented students are not eligible to receive federal financial aid for college, according to a 2014 report by the U.S. Department of Education. This requires DACA recipients, or “Dreamers”, to seek out private scholarships or pay out of pocket. If a recipient were to no longer receive protection under DACA, that recipient would lose their job as well.

Avila also says with the work permit she has, she used to be able to apply to leave the country for either humanitarian or educational purposes. However, through the Trump administration, these opportunities were taken away.

“I really wish I could travel the world but even more I wish I could see my family again,” Avila says. “[And] with the work permit I have now [of] DACA, there is no pathway to citizenship. No matter how much I want to become a citizen or how good of a person I am, there is no way for me to become a citizen [of the U.S.] as a DACA recipient.”

Despite how Avila hasn’t been able to become a citizen, East Junior Ha Nguyen and East Senior Alexis Laude have received U.S. citizenship due to the process of naturalization. According to USCIS, naturalization is the process by which U.S. citizenship is granted to a foreign citizen or national after he or she fulfills the requirements established by Congress in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).

After living in Vietnam with her family for eight years, Nguyen moved to America in July 2008 to receive better opportunities and education. According to a 2017 article written by All Law, a child can derive U.S. citizenship automatically through the naturalization of their parent.

After Nguyen’s father completed the N-400 application for naturalization and passed the civic test, both Nguyen and her father became citizens in Jan. 2018. Nguyen says the process was as frustrating due to the year long wait for background checks and forms to be approved by the federal government.

“I could tell it was very stressful for my dad [to get his citizenship]. My parents don’t speak much English, so it was hard for him,” Nguyen says. “[But] when I became a citizen I felt more relieved, like I didn’t have to worry about much anymore.”

Through this experience, Nguyen believes the system to gaining citizenship has changed through the years and wasn’t always as difficult as it was for her and her Vietnamese friends gaining citizenship as well. With this, she says she often worries about the children who come here, and their families getting deported.

“People come here because they see America as an opportunity and [it seems like] we’re shutting it off,” Nguyen says. “I think when we don’t let people [come to America], it’s stupid because not everybody is bad. I feel like everybody deserves a chance to come to America and start something new and we should welcome them.”

Though having a different experience in gaining citizenship than Nguyen, Laude agrees the system in processing applications for naturalization has become more difficult for different groups of people. After moving to the U.S. from France when he was three-years-old, and holding a green card for 13 years, Laude became a citizen alongside his father in 2016

“It was easier for me to become a citizen than others, I think, because I’m from France, and I’m white,” Laude says. “It seems like it comes down to that because I’ve heard stories of how it is harder for other people of different ethnicities to wait years to become a citizen.”

Both Nguyen and Laude agree that people coming to the U.S. seeking opportunities being granted easier access to permanent residence in the U.S. is beneficial.

“I feel like we should allow people to come in [through a faster naturalization process],” Laude says. “There are people waiting years to come here and especially if they live in a dangerous environment that could be potentially life threatening.”

According to 2016 article from Ballotpedia, the immigration policies that determine who may become a citizen of the U.S. are primarily under the responsibility of the federal government. However, states may enact their own supplementary laws and policies.

These policies can include which public services immigrants can access, establish employee screening requirements or guide the interaction between state and federal agencies. For example, in Ohio, Governor John Kasich opposes resettling the number of increased Syrian refugees.

In Nov. 2015, a spokesperson for Kasich issued a statement saying that he wrote “to the president to ask him to stop, and to ask him to stop resettling them in Ohio. We are also looking at what additional steps Ohio can take to stop resettlement of these refugees.”

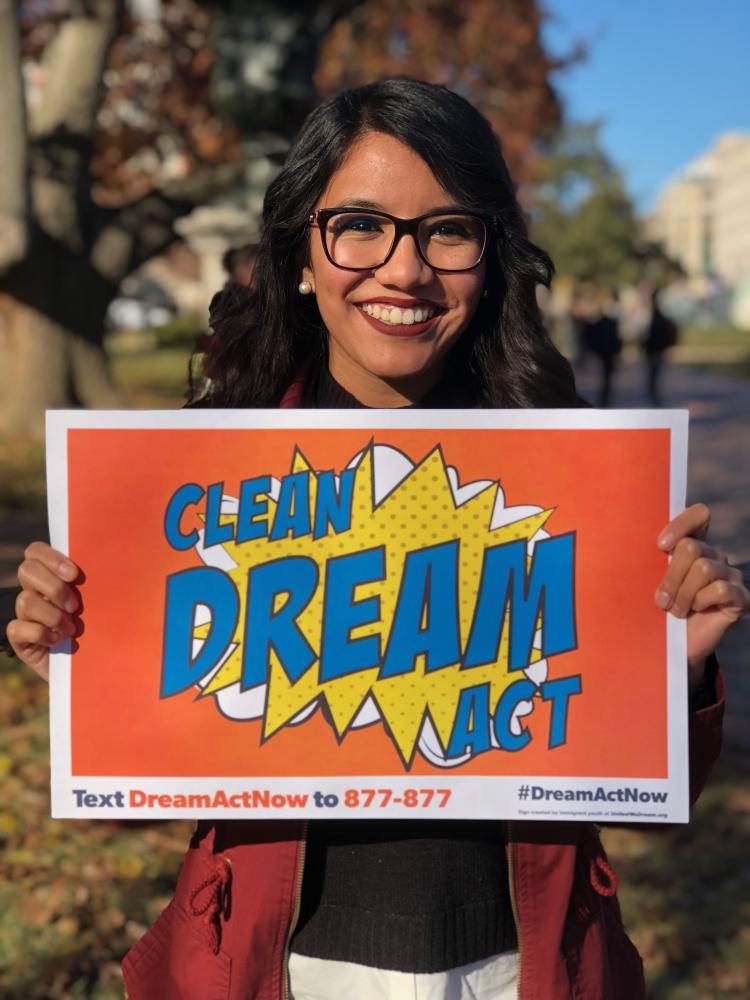

Avila supports the activism that is working for more immigration reform. Currently, she would like to see a Clean Dream Act being passed as a first step. According to a 2017 article from the National Immigration Law Center, the passing of a Clean Dream Act would ensure no funding for increased border security, interior enforcement and detention centers. Avila also wants to see states implementing Sanctuary and safety measurements.

“I strongly believe there needs to be a just and comprehensive immigration reform in U.S. that would protect all immigrants,” Avila says. “[So] that not just DACA recipients, but also their families can be safe in this country they’ve been living in and contributing to for years, if not lifetimes.”