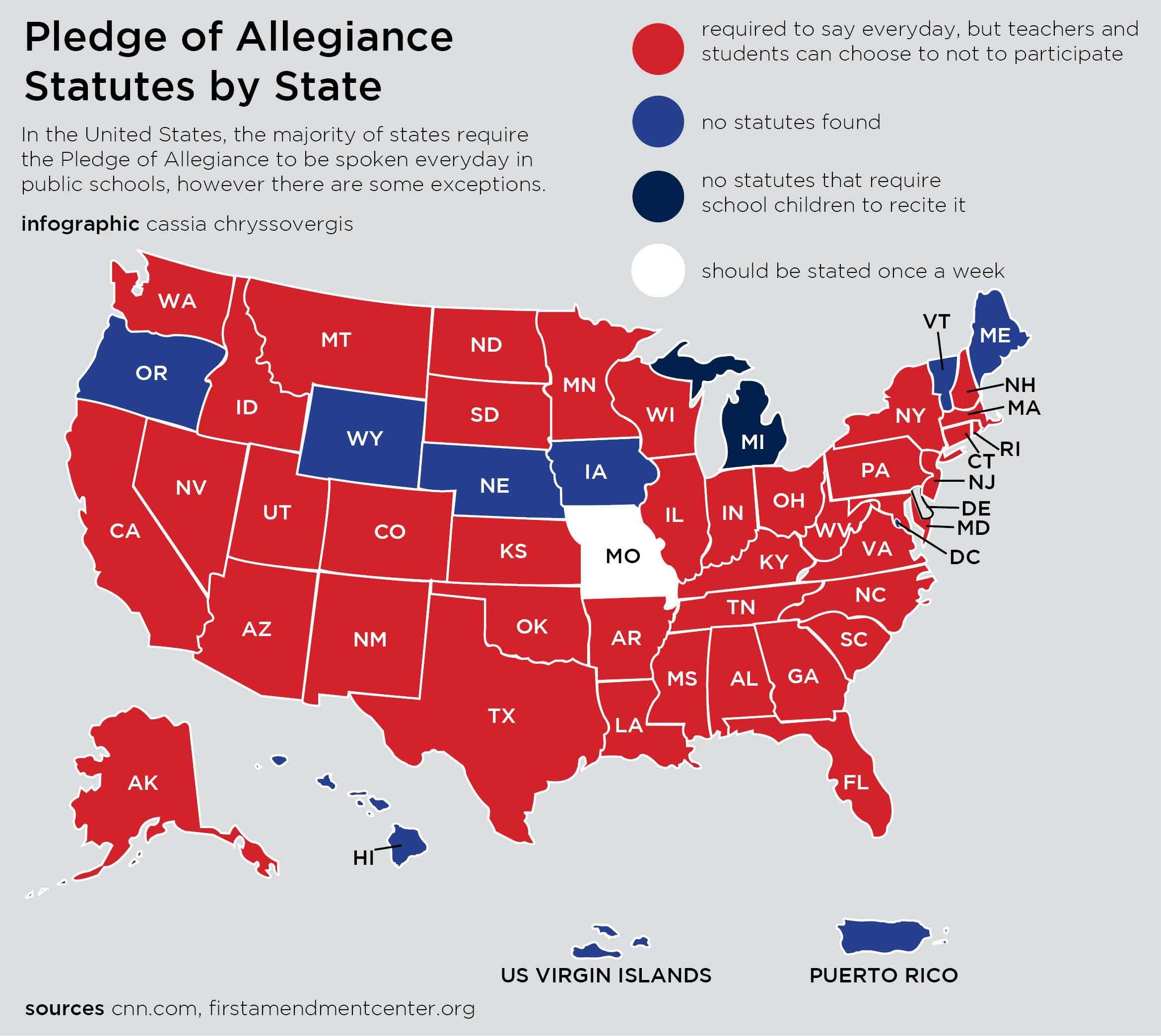

BACKGROUND ON THE PLEDGE

Story by Vivian Kolks and Sarah Yanzsa | Infographics by Cassia Chryssovergis, Vivian Kolks and Sarah Yanzsa | Art by Tyler Bonawitz

For a student attending Lakota East, each morning is almost identical. The bell rings, class begins, the intercom crackles as thousands of students prepare for the American Pledge of Allegiance. Depending on the individual student, this can mean either sitting or standing.

“Overwhelmingly kids stand, and overwhelmingly when kids stand, they’re not thinking about the Pledge,” Advanced Placement Human Geography and College Prep U.S. History teacher Matt Newell said. “They think that it’s just a routine part of their day.”

This is a routine that, according to East Principal Suzanna Davis, students can choose not to participate in.

“We invite people to stand, as is customary for the Pledge of Allegiance, but if they choose not to, then that is their choice,” Davis said. “It’s their decision for whatever reason and we don’t question that choice.”

The debate about remaining seated for the Pledge and other patriotic rituals achieved recent notoriety when NFL player Colin Kaepernick of the San Francisco 49er’s controversially refused to stand for the National Anthem in September. In response, reports of students being punished for protesting the Pledge began circulating around the country.

The controversy has made its way to East in the form of student debates. Newell, who is also the advisor for the East Chapter of Junior Statesmen of America (JSA), moderated a debate earlier in the year on the Pledge of Allegiance.

“You heard a lot of students who are very vocal about [standing for the Pledge],” Newell said. “But you also had the viewpoint of ‘listen, that’s what the flag means to you, but the flag doesn’t mean the same thing to me when I look at it.’”

For some, reciting the Pledge and honoring the American flag is a sign of patriotism. Organizations such as the American Legion stand behind these rituals in wake of the growing attention in schools and at sporting events directed at people refusing to recite the National Anthem and the Pledge.

“Our flag is a very good symbol of our national pride. It’s carried into Olympic stadiums in the opening games,” American Legion Assistant Director of Education and Scholarship Programming Tim Lankford told Spark. “To recite the Pledge of Allegiance is to remind ourselves what things are in this country that we are thankful for and pledging allegiance to.”

According to Lankford, the American Legion focuses on “veterans and their families and ensuring that they receive all of their benefits, they have community to connect to and they remain engaged in their local communities.” The organization’s main demographic, Lankford said, is “absolutely” in support of the Pledge.

The American Legion is “fully behind what the Pledge represents, how it reads and how it’s recited,” according to Lankford.

But, some people desire to change the Pledge. For example, many humanists, or people who believe in no god and base their philosophy off of history and reason, have a neutral or negative view of the Pledge and the National Anthem.

“Many humanists sympathize with Colin Kaepernick and others who feel that sitting out the [National Anthem] at sporting events is a way of protesting the mistreatment and injustices experienced by minorities,” former American Humanist Association president and current attorney David Niose told Spark.

The American Humanist Association, representing the belief of many humanists, believes that “under God” is the most controversial part of the Pledge and should be permanently omitted. According to Niose, many also believe that the “claim that the nation delivers ‘liberty and justice for all’ is problematic, because many citizens do not have liberty and justice.”

As an association, they would prefer to go back to the original version of the Pledge, which was “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” The American Humanist Association believes, according to Niose, that this original version is much more inclusive.

The origin of the phrase “under God” in the Pledge is attributed to President Eisenhower, who made the change in 1954, during the Red Scare, to differentiate the U.S. from Soviet Russia. Many believed that this would spiritually strengthen the country against the “godless communists” in Russia, where the government was attempting to eradicate religion through the promotion of atheism, according to the Smithsonian Institution’s website.

The American Legion believes that reciting the Pledge exactly how it is helps unify Americans. Because America is “the melting pot that it is,” Lankford believes that “ultimately we are all Americans and that we try to share in a common goal.”

Along with the “under God” portion, the American Humanist Association and many others who oppose the current pledge used in schools feel that the Pledge and the National Anthem promote an unhealthy nationalism instead of the intended purpose of enforcing patriotism to the United States.

“After all, isn’t the Pledge essentially a loyalty oath? What kind of country expects its citizens to recite a loyalty oath regularly?” Niose said. “It’s noteworthy that no other developed countries have a loyalty pledge as part of the regular school day.”

Newell feels almost neutral, not getting “particularly angry about it one way or another”, when talking to other people about their personal opinions on the Pledge. Instead, he sees the issue as Americans voicing their opinions in the way that they feel is best.

“To me it’s a choice Americans make, and I think that’s part of our free speech rights,” Newell said. “It’s a part of our free speech, [and] free speech protects things that citizens don’t always like.”

EAST PERSPECTIVES:

Click on a picture to read about the student’s or teacher’s perspective on the Pledge.

BRANDON CARROL

Story by Lexy Harrison

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

With a hand over his heart, he proudly stands for the Pledge out of respect for his country. East senior Brandon Caroll sees the American flag as a depiction of the men and women who fought for the United States and what the Founding Fathers set it up to be.

“The flag is a representation of our country,” Caroll said. “It’s a representation of the men and women who fought. Sitting down is not right, it’s disrespectful. I will never sit down, I’ll always stand.”

Caroll believes everyone should stand, no matter what is happening in the country, and that everyone should respect the soldiers and veterans who sacrificed their lives for people to live in the U.S.. Although he doesn’t plan to go into the military, he has two grandfathers who served in the Naval Reserves and the Army, a step-grandfather who was a paratrooper, and friends going into the service. He believes that sitting during the Pledge would directly disrespect his friends and family.

“I love my friends, I respect them,” Caroll said. “They’re going to go sacrifice their lives so I can live mine freely in this great country.”

Not only does Caroll believe that all Americans should stand for their flag, but if he were in another country and their National Anthem or flag was presented, he would follow their customs out of respect and would expect for others to do the same for his country. Even though it isn’t what he believes in, Caroll still respects those who do not to stand and the right to choose to do so.

“It’s disrespectful not to [stand], but you’re entitled to sit down if you want,” Caroll said. “[It] doesn’t matter what your opinion is, I don’t care if you’re gay, straight, black, white, purple or green, I’m going to respect you for who you are. Our opinions may differ, that’s fine, but that’s completely your right as an American.”

EKENE AZUKA

Story by Faezah Salihu

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

East senior Ekene Azuka hasn’t stood for the Pledge since the first week of September 2016.

“The reason I don’t stand for the Pledge is to call awareness to police brutality and in memory of the lives lost because of it,” Azuka said. She said that “recent shootings that have been going on with police against people of color” have influenced her decision even more.

Azuka believes that if the Pledge is not in accordance with someone’s core beliefs and values, they shouldn’t be forced to stand and say it because “people have a right to express their opinions, whether it be through words or actions.”

While she hasn’t been standing for the Pledge, she believes that she hasn’t been getting enough visibility due to the fact that she rarely attends events where the National Anthem is played, and the whole point of her not standing is so she “can start a conversation.”

She also said that she will stand for the Pledge when she believes that there is actually “liberty and justice for all,” but right now she believes “that a large portion of the country that I live in believes that I, [and] my colored brothers and sisters, are lesser because of the color of our skin.”

“I’ve dealt with a lot of discrimination because of my color in the past,” Azuka said. “For example being followed around grocery stores, being left out from discussions about advanced classes or being called ugly because my skin ‘looks like dirt.’

ANIKA-MARIE WAITS

Story by Sarah Yanzsa

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

For as long as she can remember, East senior Anika-Marie Waits has stood for the Pledge. It’s simply routine.

“That’s just what they taught you to do,” Waits said. “You stand up and that’s what you say. They didn’t really explain why you do it, it’s just kind of what I’ve been taught. It’s been a repetitive routine everyday since first grade.”

When the issue of whether or not one should stand for the National Anthem and Pledge arose, Waits said she initially formed an opinion that it was disrespectful not to stand with heavy influence from the negative stigma around the situation. Waits later changed her views based on perspectives other than the negatives ones she saw on social media, and now understands why people choose to stand and not to stand and believes both sides have good reasons to believe what they do.

“I definitely saw the reasoning for not wanting to stand, and I respect it,” Waits said. “I respect why people do want to stand as well as why they decide not to. I think they both have good reasons.”

As far as the specific words in the Pledge, Waits feels that some phrases are outdated and not applicable for everyone in the country, such as the phrases “under God” and “liberty and justice for all.” Waits knows that not everyone believes in God and not everyone is experiencing liberty and justice.

“For the most part I agree with what the Pledge stands for and what it is,” Waits said. “I think some people are too harsh when they criticize people on their beliefs and why they do or don’t stand for [the Pledge].”

ANDREW BECKER

Story by Sarah Yanzsa

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

Every day East senior Andrew Becker stands up, places his hand over his heart, and loudly recites the Pledge of Allegiance. Becker firmly believes in standing for the Pledge.

Becker’s father and grandfather both served in the military, and he has considered joining the Marines after graduating from high school. He feels that standing for the Pledge is a sign of respect for those who have served and died protecting the U.S. in the armed services.

“My grandpa died while he was in the Marines, so there was always respect for him,” Becker said. “He’s not the only one. There have been a ton of people who have [died in military service], so it feels like [not standing is] just disrespecting them.”

Becker believes the military ties he has make him feel stronger about standing for the Pledge.

“In my opinion whether you believe in certain things or not you [should stand],” Becker said. “You don’t have to recite it, you don’t have to do anything, just show respect for the people who fought for you.”

Becker also thinks that everyone should stand for the Pledge and National Anthem because he sees them as unifying acts that bring people together.

“The National Anthem is something that people can come together on,” Becker said. “I think the same thing can go for people at school [with the Pledge], rather than splitting each other up even more.”

AARON DOUGLAS

Story by Maddox Linneman

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

East junior Aaron Douglas hasn’t stood for the Pledge of Allegiance since his freshman year. He stopped standing after a Junior Statesmen of America (JSA) meeting on the subject led him “to actually advocate for what I believe in in high school.”

According to Douglas, several students have confronted him about why he sits during the Pledge, including one who, as he recalled, asked him “why [he hates] America.’” When faced with questions like these, Douglas takes the opportunity to explain his actions.

He says he doesn’t believe that refusing to stand for the Pledge is disrespectful to soldiers like some have suggested. Instead, Douglas thinks “that it’s actually more respectful to our troops to use the freedoms that they have fought for to educate myself enough to know that this is what I believe in.”

He can give several reasons for why he sits during the Pledge, including that he doesn’t believe America should be known as a “nation under God” because “our country should not run off of religion, it should run off of the Constitution.” Another is that most students learn to recite the Pledge in kindergarten.

“The fact that we aren’t taught what [the Pledge] means as kids, and we’re just told to blindly repeat it, is a problem,” Douglas said. “No kid should be forced to say it until they know what it means.”

The biggest reason that motivates Douglas to sit during the Pledge, however, is that “there isn’t ‘liberty and justice for all.’”

“We see racial injustices and people discriminated against because of their sexuality,” Douglas said. “The Pledge of Allegiance was well-intended originally, but has transformed into something hateful.”

PAYTON SOUDERS

Story by Lexy Harrison

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

East senior Payton Souders stands for the Pledge, but she understands and respects those who choose to sit.

“I do think there are some problems with our justice system, though [sitting for the Pledge is] not what I choose to do,” Souders said. “But, if that’s what other people think will make a difference, then [they can] go for it.”

To Souders, the flag represents America’s freedoms and those who have fought for the country. She believes there are better ways to protest that do not disrespect anyone such as the troops who risked their lives fighting for other Americans, but she doesn’t believe that everyone should have to stand for the Pledge.

“Honestly I don’t think [sitting for the Pledge] is as big of a deal as everyone else does,” Souders said. “When it comes down to it, it’s a piece of cloth and people put different meanings to that.”

Unless someone is actively fighting to have more liberties and freedoms, Souders believes not standing is more for personal gain, such as attention. Being a supporter of equality movements such as Black Lives Matter and gay rights, Souders supports protesting and fighting for people’s beliefs.

“There are better ways to show that you don’t appreciate what’s going on in our country,” Souders said. “The Pledge is more of a reminder for the troops and what they do for us and the liberties that we do have. That’s really something that you shouldn’t disrespect in a way to gain power or sympathy.”

RANDY CHAPMAN

Story by Lexy Harrison

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

When he first started teaching in 2001 at the old Lakota Freshman building, East World Studies teacher Randy Chapman said that he was told by other teachers and administrators to always stand for the Pledge out of respect and to make sure every student was standing as well.

Chapman has experience with students not standing for the Pledge, beginning two years ago when a student decided to not stand because of his personal views. When Chapman noticed him not standing and asked him why, Chapman recalled the student telling him that standing for the Pledge didn’t show his patriotism and that, “saying something once a day and standing for the flag wasn’t necessarily in his mind something that had much value.”

Chapman understands this because he has young children who, he said, do not know the meaning behind the Pledge but still say it because that is what they are taught.

“I think you have different time periods,” Chapman said. “People that are older like me probably went to school when there was an expectation that you stood.”

Although he was raised to stand for the Pledge and believes everyone should do the same, Chapman respects those who choose not to.

“I think we live in a country where if you just don’t want to say it, you shouldn’t be forced to say it,” Chapman said. “As long as there’s a reason behind it. I might not agree with your reason for it, but I don’t have a problem with that.”

BRANDON BRIGHT

Story by Sarah Yanzsa

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

Like the majority of people at East, College Prep and Honors physics teacher Brandon Bright stands for the Pledge of Allegiance daily, but he often stops a bit earlier than his students. This is because he chooses to say the original version: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

“As a teacher it feels like it is a professional obligation to set that standard [of standing] because that is the expectation that we expect from the students,” Bright said. “Traditionally I’ve said the original version, and I finish a lot earlier than the people on the announcements.”

One of the main reasons Bright chooses to say the original version is because of how “universally applicable” the original pledge is compared to the one recited today.

When he was in high school at East from 2000 to 2004, Bright remembers saying the more popular version of the Pledge. As a teacher at East, Bright began to say the original version of the Pledge after researching it, but he does not totally approve of saying it daily.

“I’m not convinced of the value of [saying the Pledge] every day,” Bright said. “I feel like for most people, it seems to decrease the meaning of it.”

When Bright sees a student choose to not stand during the Pledge, he acknowledges it as their personal choice.

“It’s the wonderful part of freedom of speech and freedom of expression,” Bright said. “They choose not to, and as long as they are not actively taking that time to disparage others, that seems fine to me.”

MACKENZIE ROBINETTE

Story by Faezah Salihu

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

East senior Mackenzie Robinette strongly believes in standing for the Pledge.

“Standing shows a respect for our troops and what they went through,” Robinette said. “It shows respect for our country.”

Robinette was raised in a military household. Her father served in the Army for 32 years and the Ranger Battalion for eight years as a Lieutenant Colonel.

“I’m planning on joining the Army for nursing,” Robinette said. “I want to serve my country and be able to help others around the world.”

She said that her background and military ties are what influenced her position on standing for the Pledge.

“I know that you just have to have the common decency to stand for it,” Robinette said. “Do it out of respect for the men and women who died fighting for our country.”

Robinette explained that if “you don’t want to say the Pledge, don’t say it,” but you should at least stand. She also said that “it should be mandatory to stand for the Pledge even if you don’t believe in it. It’s a sign of respect towards the country”.

“When I went to Thailand for a mission trip, I would pay my respects to their king and their religion even though I’m not a Thai citizen or a Buddhist,” Robinette said. “I did it because I was being respectful of their country.”

HANNAH MATEJKOVIC

Story by Vivian Kolks

Photo Illustration by Emma Stiefel

Art by Tyler Bonawitz

The first time East senior Hannah Matejkovic didn’t stand for the Pledge of Allegiance during her senior year, no one in her first period class noticed. She remained sitting the next day and the next. When a seating change moved her to the front of the room, she kept at it.

“People were talking about not standing for a while, I just thought if they’re doing it why can’t I? Now or never,” Matejkovic said. “It’s my belief, [and] I’m allowed to do what I want.”

However, one of her classmates didn’t agree and, according to Matejkovic, accused her of being disrespectful.

“He asked me to give him a reason for not standing,” Matejkovic said. “I told him that I had several.”

Matejkovic focuses on the minorities she said are being negatively affected by today’s society.

“Some of it is going with the Black Lives Matter movement and how some people are saying that All Lives Matter,” Matejkovic said. The LGBT and Muslim communities also have her support, stemming from Matejkovic’s belief that they are “not being treated like Americans.”

“The LGBT community is not being treated right,” Matejkovic said. “This community is being killed just [because] people are ignorant and don’t believe that they have the right to live.”

Another controversial part of the Pledge that justifies not standing, according to Matejkovic, is the phrase “under God.”

“America is supposed to be for any religion. We shouldn’t say ‘under God’ because some people are atheists,” Matejkovic said.

Matejkovic also doesn’t understand why so many people are against sitting for the Pledge when their negative energy could be focused on better things.

“Why are we standing up every morning and saying meaningless words?” Matejkovic said. “Why are we saying [the Pledge] if we’re not going to do anything that it says?”