Oftentimes words derive from a certain place or context,” 24- year Lakota teacher and Gifted Intervention Specialist Aaron Nunley told Spark, “but [my students] started using words you just couldn’t trace back to anything specific.”

After spending years trying to teach kids through a barrier of language formed by nonsensical trends in media, Nunley employed a neologism of his own.

Pursuing a connection with his students and displaying how language travels through community, Nunley tried an experiment with his Plains Junior students.

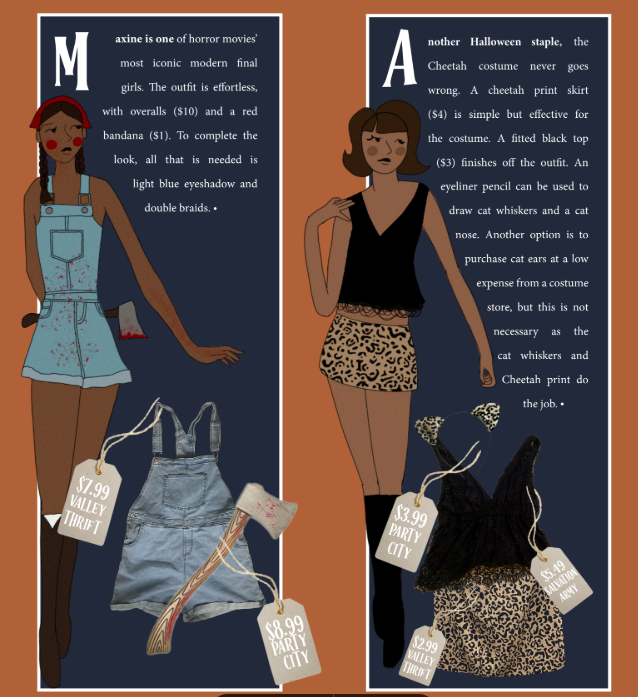

During his 8th grade math class, he decided to coin the term “binder” to mean “good.” He then instructed his students to use it and observe how long it takes before it becomes a part of the student-body’s vernacular.

“[Two days later] I went to a staff meeting and they opened the meeting with: ‘for some reason all the kids are saying [binder]. We just need to make sure that it’s not an inappropriate reference,” said Nunley. “And I’m just dying laughing.”

After attending the Plains Junior staff meeting, Nunley went back to his students and shared his experience.

“I told this to students; they thought it was really funny,” said Nunley. “So we decided to kill it, so if anybody uses ‘binder’ to mean ‘good’ we are going to look at them like we have no idea what they are talking about. [We] killed it within a day.”

“Brain rot” is a newly popularized word that the Oxford English Dictionary characterized as an overconsumption of pointless online media.

The term is most regularly used to label trivial content or a person’s deteriorating mental state from consuming it.

This word about seemingly irrelevant content was culturally relevant enough to inspire the staff at Oxford English Dictionary to make “brain rot” their word of the year.

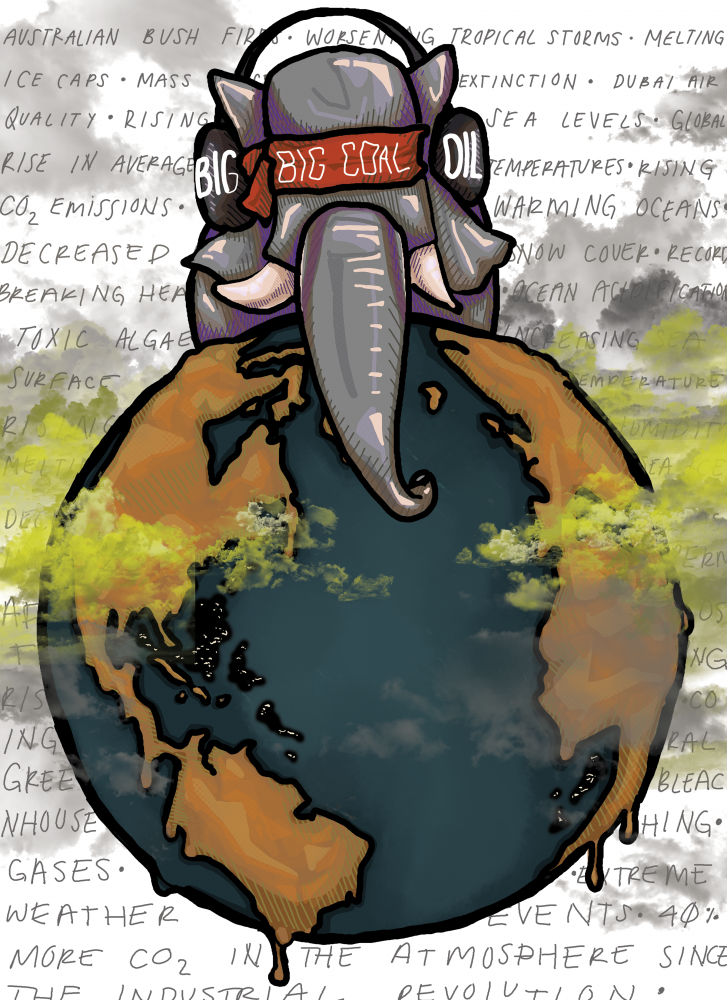

The younger generation’s contribution to internet culture is often labeled as “brain rot” in a derogatory way to highlight its lack of substance and tendency for low quality.

Lowering Media Barriers

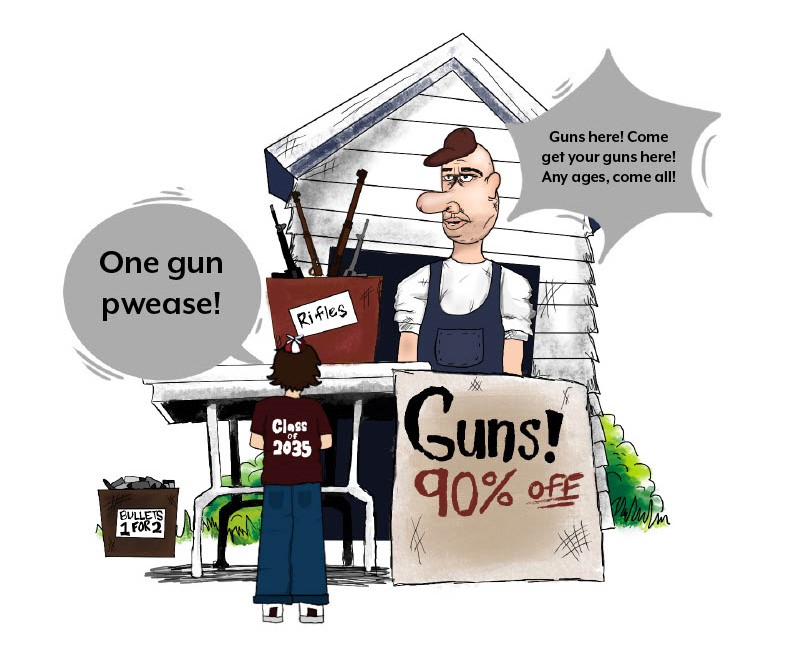

According to Professor and Chair of Mediated Communication at the School of Communication at The Ohio State University Scott Campbell, unlike other forms of media, social media lowers barriers to participation in communication which can lower the quality of it.

“It used to be that the media was very vertical, very centralized. You had to have power or money to get represented in mass communication channels,” Campbell told Spark. “So [with social media] anybody can have a voice, lowering the gatekeeping barriers of what gets said.”

As stated by Professor of Visual Communications at Ohio University, Stan Alost, the media used to have a “gatekeeper.” This is the process of media getting filtered before being disseminated, verifying validity and truth before it reaches the public. With the gatekeeping system, the opportunity of average people to create their own content is difficult.

“The legacy media used to [have a] gatekeeper,” Alost told Spark. “If you had a message you wanted to get out, you had to go through them.”

The lack of filtration in media directly connects to the way in which people communicate according to Ron Becker, professor of Media and Communication at Miami University. He labels online communication as either “mass personal communication” or “interpersonal communication.”

Mass personal communication is a way to describe how media is used by creators to interact with their audience. Large institutions create a message designed for a huge audience.

Interpersonal communication describes a message sent out intended for a smaller audience about a personal detail.

“Social media sort of encourages a new kind of communication that blurs the boundary between mass and interpersonal communication,” said Becker.

Becker offered an example to better understand this concept.

“30 years ago, you would go on vacation, you would take your pictures, you would get them developed, and then you would have friends over, and you would show your friends the photos you took on your vacation. [This is] a kind of interpersonal communication.”

With the development of social media however, Becker said that a person can now post those photos on Instagram or another platform for everyone to see. With this, he said, personal lives become public which increases mass interpersonal communication.

According to Becker and Alost, the consequence of the lack of filtration on social media is that audiences are now skeptical and untrusting.

“Journalistically, you had editors; you had vetting systems. You had copy editors, so by the time the information got to the audience, you could fairly well trust it. There were a lot of ethics involved,” said Alost. “Now there’s a lot of advocacy [from ordinary people], but who do we trust? There is not a quick and easy way to identify who has a hidden agenda.”

Craving Authenticity

However, Alost said that the ability for anyone to share on social media might create a more democratic media.

“Anybody with a smartphone can communicate; they can create the content,” said Alost. “The difficulty is finding an audience that is broad enough [to listen], and what we find, particularly with social media, is that the audience is pretty finicky.”

He said that with this, social media becomes more performative. Content creators may put more emphasis on creating a wide audience as opposed to connecting with their viewers in meaningful ways.

“You never really are sure what’s going to connect with people,” said Alost. “And what I do find refreshing or rewarding, and as I look at the younger group coming through the field of communication as well as audiences, is that the younger generations really want ‘real.’”

According to him, the younger generations are less impressed with big corporations and are looking for authenticity in content creation.

“I think that the audiences, when they perceive something as being corporate, as being somebody trying to feed you something, they are quick to move away from it,” said Alost. “The opposite of that is when audiences [falsely] perceive something as real and genuine, and it gets a lot of attention.”

In contrast, Alost said older generations hold their media to different standards, meaning they “did not question [authenticity] in the same way” that younger generations do.

Lowering Attention Spans

Though younger audiences crave authenticity, according to Alost, they are typically only passively observing by letting the content wash over them, “skimming through a lot of stuff without going very deep.”

Scrolling through hundreds of 15-second videos without looking further into their topics may limit viewer attentiveness, leading the viewer to lose all information from the media consumed.

“Our eyes send a whole lot of information back to our brain, and our brain throws out most of it because it is meaningless,” said Alost.

The stereotype that younger generations have shorter attention spans is common according to Alost, who said that the content curated for them may perpetuate this issue.

“This label of a short attention span has been put onto the younger generation because of the cluttered landscape of media,” said Alost.

When given the chance to consume meaningful media however, he said that younger generations will spend the time with it.

“It is why you binge shows, watch movies, read books,” said Alost.

According to Campbell, media has changed in a slightly different way.

“It used to be that media, a lot of it was archiving stuff, like journaling or taking pictures that you save and look at later,” said Campbell. “Media today is more about, ‘Hey check out what I’m up to right now,’ and then letting it go. That is the spirit behind Snapchat; ephemeral images that go away.”

Alost is also familiar with this fleeting nature of short-form media content.

“I worked in the news industry at a time they started doing eye-tracking research (scientists studying people’s gaze as they view content),” said Alost. “The mantra was ‘people are only spending a few seconds looking at this,’ so you made [the content] very simple.”

Alost said that when content creators simplify text, images, and audio to limit distractions, viewers spend less time with it because material is not there.

The simplification of this short-form, short- lived content may lead to lost nuances, creating substanceless media.

A Lack of Substance

This perception directly correlates to the language that is used in media according to Becker.

“In the 1960s, a term like ‘groovy’ came from somewhere and then gradually filtered through youth culture,” said Becker. “It took years for it to become popular. The rate at which it evolved was so slow that there could be an agreement on what ‘groovy’ meant.”

Popular ‘brain rot’ terms like ‘skibidi’ suddenly became widely used at a rapid pace on social media so that people did not get the chance to come to a consensus on what the word means.

Instead, the term ‘skibidi’ evolves with every new post, according to Becker.

“[Content creators] apply the terminology to their content, adding a different layer to the meaning of ‘skibidi’ every time,” said Becker.

The ability for language to spread in this way did not exist prior to the rise of social media.

“What happens is [there is an] incentive to say, ‘here is this new term, I’m going to use it to be cool on Instagram.’ Which sort of incentivizes people to participate in an artificial way,” said Becker.

The lack of a formal definition for a word may give the impression that there is no substance to it, but Becker and Campbell are able to see the value in these ‘brain rot’ terms.

“The meaning comes from simply participating [in saying the word],” said Becker.

When a content creator employs ‘skibidi’ in a wacky way, their audience may respond with laughter which can build a connection through the screen.

“I think [younger generations’] humor and laughing generates social cohesion,” said Campbell. “I think that is the substance of it. Even a stupid joke still fosters humor.”

Assistant Professor at the School of Communication at The Ohio State University, Sara Grady, said she believes that the term “brain rot” to describe Generation Z’s slang is extreme.

“People have been freaking out about young people’s brains rotting from substance-less pop culture for centuries,” Grady told Spark, “and despite this we haven’t all turned into vegetables!”

Moving Language Through Media

Becker also recognizes the history of slang outside of ‘brain rot.’

“It is not new that [trendy terms] lack [clear] substance,” he said, “but it is new how we communicate them.”

According to Grady, slang moves through online spaces in very interesting ways, though these ways are not entirely separate from how it has evolved in a pre-social media era.

“This process might be faster in online spaces because we have what’s called ‘context collapse,’” said Grady.

A context collapse refers to the spread of a new term that becomes popularized. An example of this would be hearing a friend use a new word and adopting it, causing others to hear it and adopt it as well.

“That is how language moves through groups,” said Grady. “This dissemination process is the same whether it happens online or in-person.”

The difference between context collapse in- person and context collapse on social media is the size of the audience.

“Imagine that before, your friend would have used this new word in private and with just a close group of friends,” said Grady. “It would take longer for people she does not know to catch on since they were not in the inner circle.”

When that friend uses social media today, Grady said, many people who are not in that inner circle might hear and see her usage. This may allow a much wider range of people to have potential access to her term, causing them to adopt it quicker than if her audience was smaller.

Internet terms often move fast from social media to school grounds, according to East junior Hafsa Raja.

“I remember when everyone participated in the ‘dabloons’ trend,” Raja told Spark. “I think it was around for a week or two before everyone became bored of it.”

This short-lived trend, primarily on TikTok, mimicked capitalism. It was a trend where “dabloons” were currency that viewers would hypothetically “collect” when they organically discovered certain videos on their feed.

“That’s the kind of nature I see a lot when I’m online,” said Raja. “Things move fast; sometimes it’s hard to even know what some of it means [before it is gone].”