The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)’s 2022 annual homeless assessment reported that 582,462 people in America were experiencing homelessness on a single night in January 2022.

In an effort to address this crisis, large sums from big cities’ annual budgets were allocated towards homelessness. In 2023, New York City’s Department of Homeless Service projected $2.2 billion, Los Angeles County Homeless Initiative forecasted $609 million, and Seattle’s Human Service Department estimated $111 million.

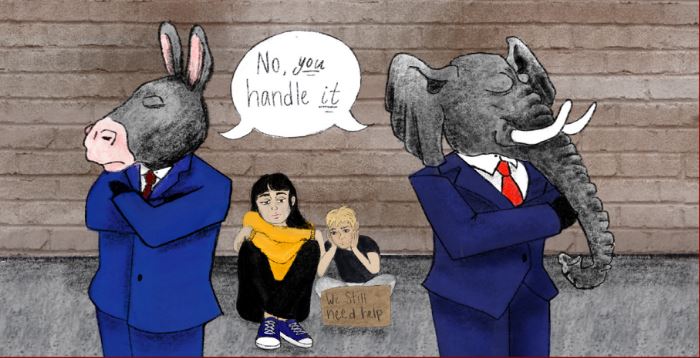

This money goes towards emergency shelters, employment, job training programs, and other services to aid the homeless. The effect of these figures indicate one singular thing: the response to the homeless crisis is not working.

The policies of the Reagan administration in the 1980s played a major role in shaping housing issues that still impact homelessness today.

According to the National Library of Medicine, when first introduced to America, the term “homeless” was used to describe a person’s character, rather than their actual living situation. Popularized by the surge of urban areas, the term was commonly used to describe individuals searching for work in the city. The phrase concentrated more on how the lack of stability affects their character.

The early 1980s marked the beginning of the emergence of the popularized, modern term which one would know as “homeless.” At this point, homelessness became a severe issue that needed immediate attention.

In 1978, HUD’s budget was over $83 billion, a level of funding which directly represents the federal government’s level of dedication to eradicate the issue of homelessness by building, maintaining, and subsidizing affordable housing.

Keeping the HUD budget high is essential to benefit homeless individuals. With that funding, there is increased housing availability, more supportive services, and an increase in public health and safety.

When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, many social programs were dismantled that were designed to assist the poor, one being the federal funding of affordable housing production.

By 1983, HUD’s budget had fallen to $18 billion (adjusted for inflation).

According to Liberation News by the end of Reagan’s second term in 1989, subsidized housing programs had been cut by 80.7 percent. This directly impacted the efficiency of the program, from 1976 to 1982, over 755,000 new public units were built. A striking difference from 1983 to 2007, where only 256,000 units were built by HUD.

According to the National Institutes of Health, the homeless population in the late 1980s was estimated to be between 400,000 to 600,000 people compared to an estimated 125,000 in 1980.

Though there are many contributing factors to this increase, including the economic downturn in the 1970s and the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill, there is a direct link attributed to policy changes that cutback on affordable housing programs.

Reports from the Congressional Budget Office show that house related tax expenditures increased by 281% from $32 billion to $121.8 billion. This gives a tax break to individuals who deduct the interest on their mortgage, an effort to encourage people to take out mortgages and purchase a home rather than rent.

By enhancing the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction, low income renters were left to depend on a declining HUD fund while high- interest mortgage holders were receiving the largest deductions.

Reagan eliminated poor people’s housing subsidies and tripled home ownership; this is because there is no money to be found in helping low income renters and the homeless and therefore is no profit for corporate America. This is unlike the high-interest mortgage holders, which financially benefits big mortgage industries, banks, and the construction industry.

The cultural shift in homelessness in the early 1980s, widely due to Ronald Reagan’s reducing social programs, still affects America today. The long term solution to solve this problem does not lie in the immediate financial aid in big cities, but in the shift of government social policies.