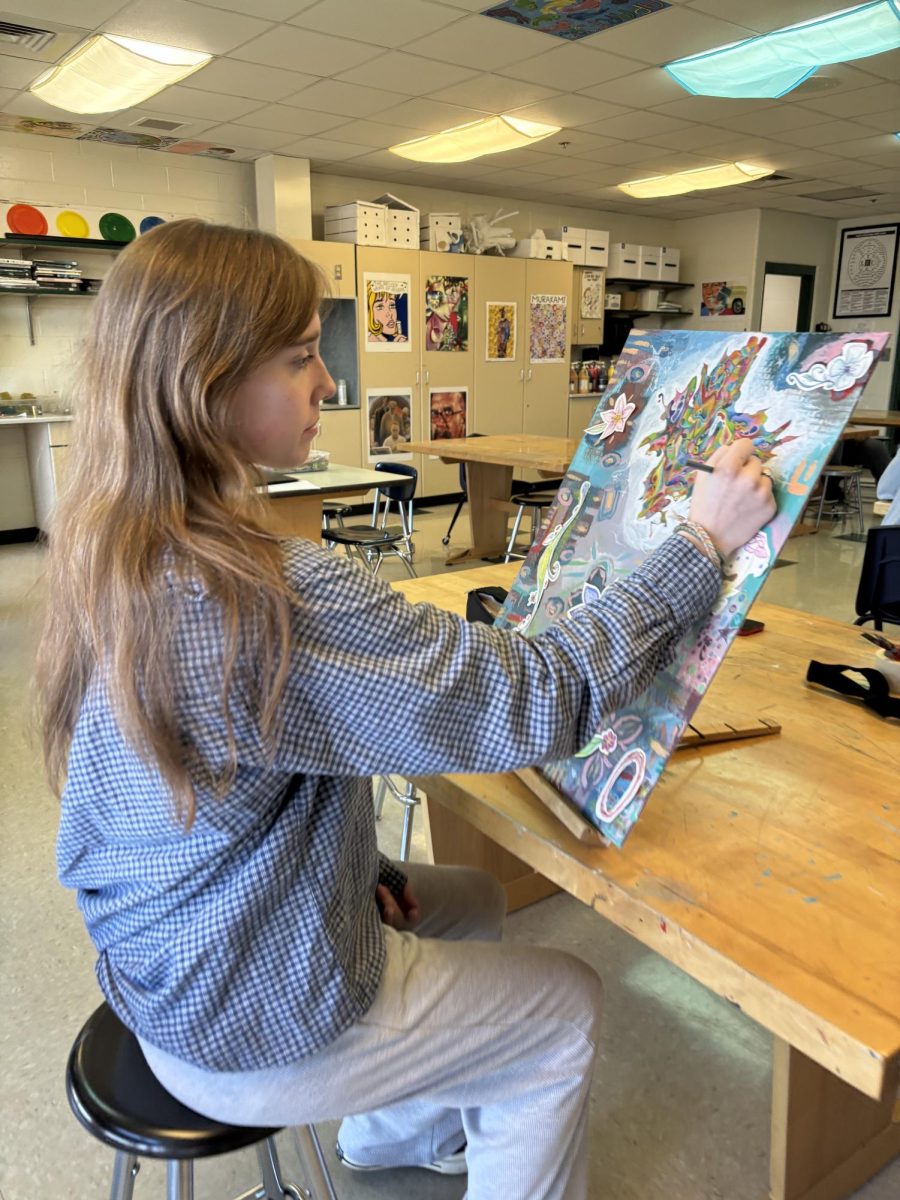

story by Alexandra Fernholz | photography by Isis Summerlin

*denotes name change

A plume of vapor rises from the lips of a young model who stares sultrily into the camera, one hand on her hip and the other holding the now infamous Juul. Wearing leggings and a grey jacket pulled aside to reveal a white crop top and a belly button, she has her hair pulled into a high ponytail. This photograph of the model against the bright, eye-catching yellow background is one of many from the 2015 Vaporized campaign. The campaign was funded by PAX Labs, the maker of the Juul and owner of Juul Labs, a subsidiary which broke off as its own company in 2017.

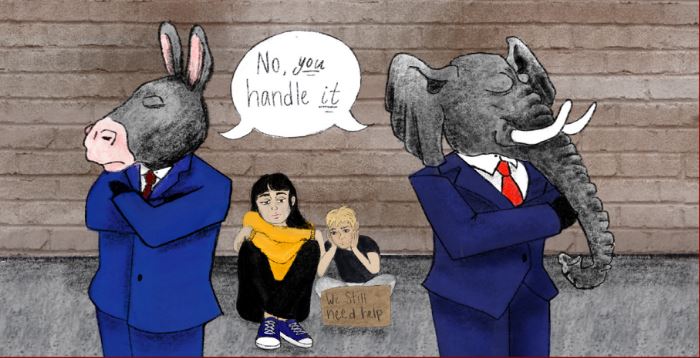

These original Juul ad campaigns were all of similar styles, featuring young, trendy looking models, bright colors, and the seeming idea that juuling was something done by “cool people.” However, Juul is now under scrutiny by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for potentially luring its customers into something much less harmless than it seemed—especially the underage consumers.

“In its early marketing efforts, about 2015 or 2016, [Juul] actually had a pretty explicit intent to target young adults,” Annenberg School of Communication Doctoral Candidate Sijia Yang told Spark. “Social influence is one of the biggest reasons [teens] cited for why they wanted to use e-cigarettes.”

For East junior Madison*, this was exactly the case. She first tried a Juul at the beginning of her junior year after Riley*, a friend of hers, expressed interest in getting one. Riley had previously juuled, but after her parents found and confiscated her device, Riley became intent on having a replacement. After agreeing to split the cost of the Juul, Madison and Riley drove to an old gas station in Mason to pick up the device.

“[We went to] a sketchy gas station. The guy who worked there knew [Riley] from one of her friends,” Madison said. “It was really sketchy. I thought ‘what did I get myself into?’”

After purchasing the Juul, Riley wasted no time in testing out the device.

“She broke it out like right then [in the car],” Madison said. “She was like, ‘ready?’ and I was like, ‘what?’”

For millions of teens, a Juul is not an uncommon device. According to the 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), almost five million youth, or 20.8 percent of adolescents, currently use some form of a tobacco product. Of these five million, 3.6 million reported using e-cigarettes.

72 percent of East students have seen an ad for either a Juul or similar vaping device within the past year.

Despite this large percentage, only 37 percent of surveyed youth and young adult users knew that a Juul pod always contains nicotine, according to a recent study by the Truth Initiative, a national tobacco prevention campaign. Professor of Pediatrics at Stanford University Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, who also works as part of the Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising research group, has spoken to many adolescents on the subject.

“[Teens] think that [pods are] basically harmless, or just water vapor, without realizing that there’s a significant amount of nicotine and other chemicals in the Juuls,” Halpern-Felsher told Spark. “We’re basically creating a generation of people who are now addicted to tobacco or nicotine through e-cigarettes rather than through cigarettes.”

E-cigarettes were first introduced to the United States (US) market in 2006, but the FDA was not authorized to regulate tobacco products until the Family Prevention and Tobacco Control Act was signed by former President Obama in 2009. And up until 2011, it was still uncertain whether e-cigarettes should be classified as tobacco products.

In April of 2011, the FDA announced its intention to regulate e-cigarettes as tobacco products. This meant that any retailer who sold e-cigarettes would have to check the ID of any customer under 27 and refuse to sell to any customer under 18. The new decision also prohibited sales of e-cigarettes from a vending machine (except in adult-only facilities), and prohibited free samples or parts to be given away to consumers.

In Juul’s infamous 2015 Vaporized campaign, there are no clearly visible warnings about nicotine or the possibility of addiction in the advertisements, unlike those present in ads for other tobacco products. These labels warning consumers of the potential dangers of an e-cigarette were not required by the FDA until Aug. 10, 2018.

“Juul didn’t make explicit claims that e-cigarettes are harmless,” Yang said. “[But] those marketing ads are pretty persuasive in terms of making young adults think that e-cigarette use is less harmful and a safer option to smoking.”

In a recent survey, 72 percent of East students have seen an ad for either a Juul or similar vaping device within the past year.

Madison has observed e-cigarettes around her, not only at school, but behind closed doors, and sometimes around dumpsters at her job at a popular chain restaurant.

“I know other people who do it and that’s all they do,” Madison said. “Everyone openly talks about it, because no one cares.”

When Vaporized first launched in July 2015, Juul spent over $1 million to market the product online, expanding its presence on social media platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter.

“One of the things Juul did differently than others is that [they] very explicitly targeted social media as one of the major outlets for its marketing efforts,” Yang said. “Young adults heavily rely upon social media all the time—that definitely got to them.”

Other key parts of the campaign in the summer of 2015 included a series of launch parties featuring youth-oriented bands, free tastings, and a key feature: flavored pods.

According to the 2016 National Youth Tobacco Survey, 31 percent of surveyed youth cited the availability of flavors as the reason they started using e-cigarettes. Some even believe, incorrectly, that the flavored devices are not harmful at all.

“From talking to youth, they have said to us that they really like to have something that’s tasty, without calories or without as much harm as they think it has,” Halpern-Felsher said. “We’re meant to eat cheese, we’re meant to eat milk chocolate, we’re not meant to heat them up and inhale it. And so the buttery flavors, the cinnamon flavors, and the vanilla flavors [available in pods] can be very harmful to your lungs and to your respiratory system.”

Out of 100 East students surveyed, 65 percent claim to juul. 22 percent cited the flavors as their reason for trying the device. 19 percent said it was because the device “looked cool.” 60 percent said they juuled because their friends did it.

While cigarette flavors other than menthol were banned by the FDA in 2009, stopping the sale of kid-friendly flavors like chocolate and strawberry, other tobacco products were not subjected to the same law. For this reason, cartridges of e-liquid flavored and packaged as Swedish Fish, Juicy Fruit gum, Skittles, and even Thin Mints were available online and in stores.

Taking advantage of this legal discrepancy allowed Juul sales to jump nearly 800 percent from 2017 to 2018. As of December 2018, after American tobacco giant Altria acquired a 35 percent share in Juul stock, the company was valued at $38 billion, more than both SpaceX and Airbnb.

Despite public concerns, Juul continues to grow. According to Bloomberg News, Juul’s 2018 revenue stood at $1.3 billion and the company made a profit of $12.4 million that year, making it one of the most successful startups in the world. And in 2019, sales growth is predicted to balloon another 160 percent.

“Nothing is happening, with [Juul] being forced to stop selling certain flavors,” Madison said. “Even if they do stop selling, people are still going to find a way to get it.”

According to Halpern-Felsher, Juul is popular for a variety of reasons.

“They are marketed as being cool, and they’re marketed as being flashy,” Halpern-Felsher said. “Youth tell me that it’s also because they can hide it [easily].”

However, though Juul Labs has reportedly invested $30 million toward youth and parent education and independent research, it insisted in a July 2018 press release that the company marketed its product “responsibly” and followed “strict guidelines” to market the product to adult smokers looking to stop.

“We have never marketed to anyone underage,” Juul said in the July 2018 press release. “Our growth is not the result of marketing but rather a superior product disrupting an archaic industry.”

In Madison’s experience, Juul is popular among her friends, classmates, and co-workers because of its size.

“[The Juuls are] small and you can carry [them] in your pocket,” Madison said. “I know a lot of people do. It’s very portable. It’s everywhere here.”

For Riley, portability meant accessibility. And having access to a Juul led her to nearly constant use.

“Back in December, [Riley] would ask me constantly for it. I started taking it from her because I was trying to get her to stop,” Madison said. “She couldn’t function without it.”

Up until that time, Madison says, she and Riley had switched who bought pods, alternating purchases and sharing each pack. Then Riley started using more and more.

“There’s like four [pods] in a pack. And it would be gone within two days,” Madison said.

According to Vice President of Prevention and Public Health Policy of the Health Policy Institute of Ohio Amy Bush Stevens, one of the biggest concerns among officials is the likelihood of dual-use among adolescents who use e-cigarettes. Dual-use, which is the use of both e-cigarettes and traditional tobacco products, is reportedly common among e-cigarette users. The 2018 NYTS survey found that among adolescents who used tobacco products, 40 percent used more than one.

“Once you become dependent on nicotine, then people will often move to dual-use, using both e-cigarettes and traditional tobacco,” Bush Stevens said. “Up to this point, you see really good reductions in traditional cigarette smoking among adolescents in the US and in Ohio and that’s fantastic. It’s really concerning because it threatens to undo all of the progress that we have made.”

But times have changed since the original Vaporized campaign in the summer of 2015. In September of 2018, the now former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb declared youth vaping to be an “epidemic” and gave Juul and several other major e-cigarette manufacturers 60 days to submit plans to prevent youth vaping to the FDA.

“We’re basically creating a generation of people who are now addicted to tobacco or nicotine through e-cigarettes rather than through cigarettes.”

Then in November, Juul halted sales of mango, crème brûlée, cucumber, and fruit-flavored pods at over 90,000 retail stores, and shut down both its Facebook and Instagram accounts in response to the FDA’s crackdown. However, these flavors are still available online. And in March of 2019, Washington became the ninth state to raise the legal smoking and vaping age to 21, after Hawaii, California, New Jersey, and others. The previous minimum age issued nationally by the FDA is 18.

In the wake of pressure from the federal government and negative media scrutiny, Juul has also rebranded itself, featuring images of former smokers who quit traditional cigarettes using a Juul. Rather than their former campaign of young and trendy models, it now places an emphasis on juuling as a viable option for adults who want to quit smoking rather than a new trendy fad. However, this new version of Juul may not be entirely accurate, either.

“There is really no good evidence to show that adults successfully quit,” Halpern-Felsher said. “Instead a lot of the evidence shows that adults who try quitting with e-cigarettes wind up using cigarettes and e-cigarettes, which is a bigger problem.”

Yang also emphasized the difference in age between adult and young adult users. Adults who had previously used tobacco products reacted differently to the nicotine than those who had never experienced it before.

“Scientifically speaking, the long term health impact still remains largely unknown,” Yang said. “We don’t quite understand [Juul’s] long term impact on people’s health, but we know for sure that for young adults it causes an addiction [to nicotine].”

According to Bush Stevens, education is just as important as long-term research.

“We want to make sure that we prevent as many kids from starting a nicotine [dependency] before that addiction is fully established,” Bush Stevens said. “We need to continue to educate and improve that knowledge and awareness. That’s really important.”

In Madison’s experience, her peers know all about juuling but may not have known the dangers behind it when they started.

“Everyone started hearing about it because it was advertised everywhere on all the social media, places like Snapchat and Instagram. We grew up watching these people around a similar age, or a couple of years older than us [smoking and juuling]. That’s what they were all doing,” Madison said. “I’m planning on completely getting rid of [my Juul], because I don’t want to use it [anymore].”