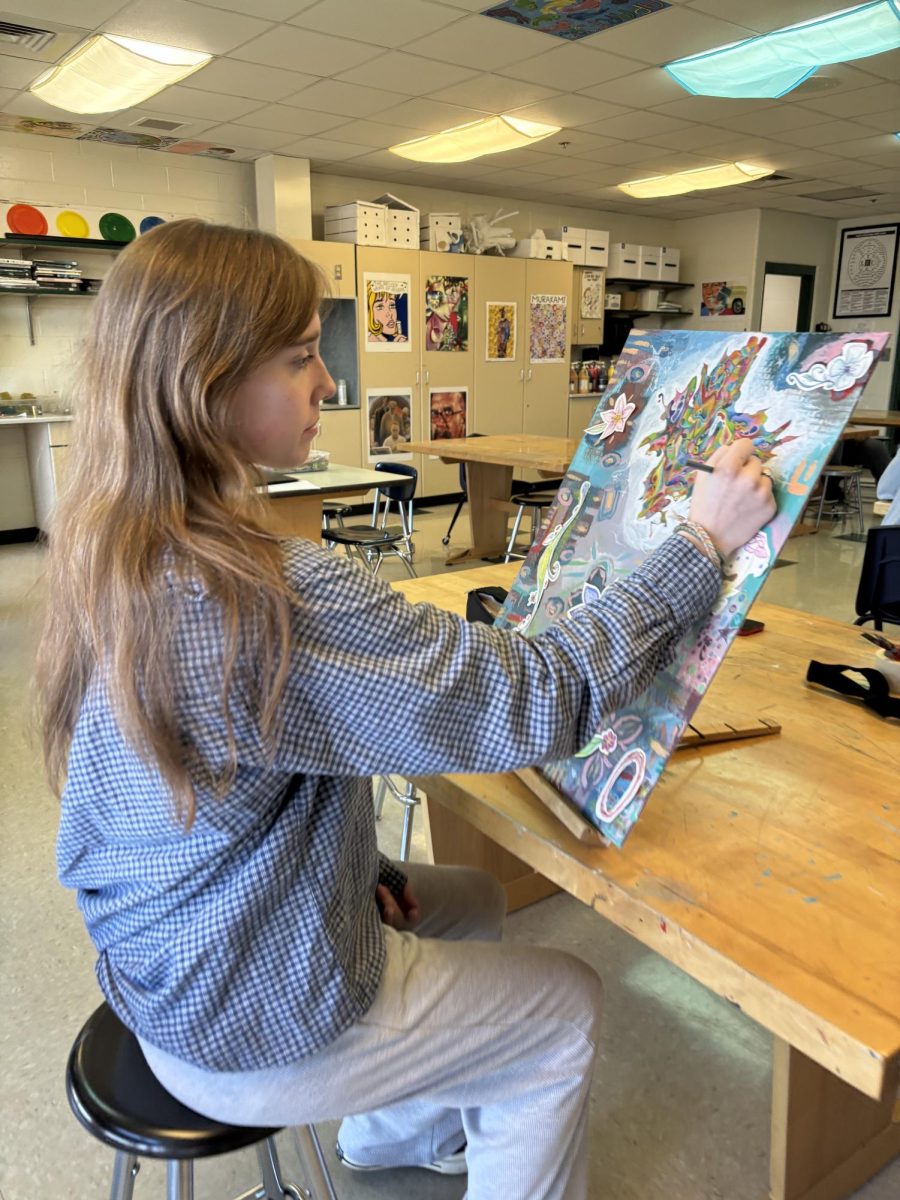

Story and Photography by Emma Stiefel

The Push for Policy

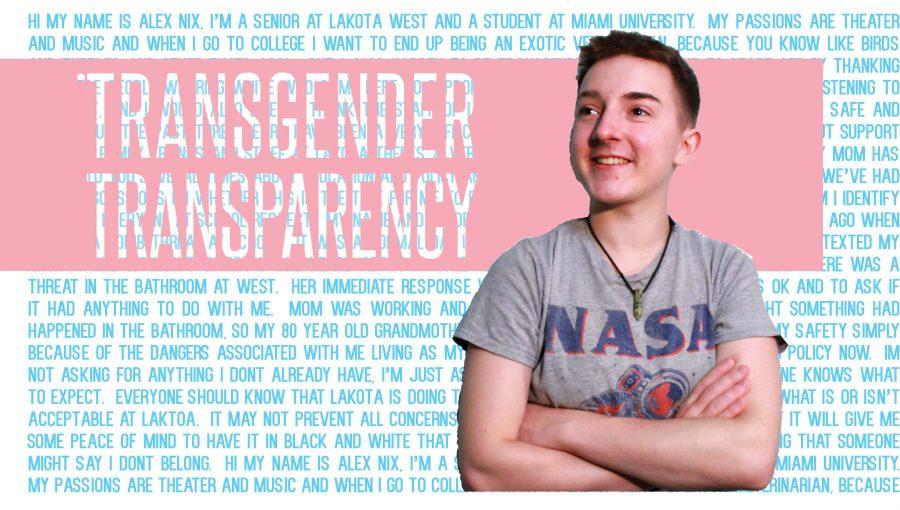

He began by introducing himself. Alex Nix, senior at Lakota West, passionate actor and musician, and aspiring exotic veterinarian (his two pet birds sat on his shoulders for his entire interview).

“But,” he told the Lakota Board of Education at its Sept. 26 meeting, “I also happen to be transgender.”

At West, Alex said, he’s able to use the bathroom that matches his gender identity and his name and pronouns are respected. He wasn’t there to ask the board for any accommodations he doesn’t already have.

Instead, he wants Lakota to create a policy specifically protecting transgender students’ rights. Without such a policy in place, Alex and his mother, Linda Nix, fear that the welcoming environment he’s experienced so far could disappear too easily.

“Everyone should know that Lakota is doing the right thing, and everyone should know what is or isn’t acceptable at Lakota,” Alex told Spark. “It will give me some peace of mind to have it in black and white that I can use the bathroom without worrying that someone might say I don’t belong.”

Linda has spoken to the board about the subject herself several times and wants to ensure “that a kid who starts in kindergarten is going to be treated the same way throughout their course [at Lakota].” She decided to push for a policy after discussing school issues with other parents who attend the Cincinnati Children’s Transgender Health Clinic support group.

Lakota School Board Member Ray Murray has openly supported creating such a policy. He serves on Lakota’s policy committee and wrote two drafts outlining the rights of transgender students in the district.

A policy, according to Murray, would “be an affirmation that the board understands transgender [students].” It would include definitions of terms such as “transgender” and “gender identity” and then list what schools must do for transgender students if they ask, including using their preferred name and pronouns and allowing them to use the restroom that corresponds with their gender identity.

“[The policy would say that] we understand that every child has the right to a quality education no matter what their status is,” Murray said. “And that we support the parents of [transgender] kids and realize the special things that we must consider to support them, and it would spell out what they would be able to get.”

Murray wasn’t familiar with the subject, however, until a Lakota parent spoke to him about their young transgender student and he “realized quickly that the child needs support in every way.

“Especially because most kids that age, [who are in the district from] kindergarten to twelfth grade, spend 70 percent of their time in school,” Murray told Spark. “We need to make it a safe environment for them.”

One such transgender student is Lakota second grader Ryan Smith*. His mother Sarah Smith* asked not to be named because she “doesn’t get to choose that he becomes the poster child for [transgender students’ rights].”

Sarah has been advocating for a policy “through a lot of conversations.” While she’s not attended any board meetings, she gave a presentation to the staff at Ryan’s school about transgender students and has spoken to individual board members about the subject.

“Policy needs to be done to protect the children,” Sarah said. “They have the right to learn, they have the right to not be segregated, and they have the right to use the restroom.”

According to Sarah, Ryan is just like any other kid. He plays on a boys’ baseball team. He gets invited to sleepovers, trampoline parties and Pump It Up birthdays.

Ryan’s elementary school has helped; he’s “treated like any other student” and uses the boys’ restroom. Sarah, like the Nixes, wants a policy to ensure that he doesn’t lose the school’s support.

Lakota’s Current Practices

At the Oct. 24 school board meeting, however, Lakota Board of Education President Lynda O’Connor told Linda Nix that no policy would be created. Lakota Acting Superintendent Robb Vogelmann told Spark in a written response that “we certainly appreciate the strong advocacy we heard from some of our parents, and hope they can understand the gravity with which our board approaches these decisions.”

The board decided to not adopt a new policy specific to transgender students “after extensive consideration, training, and research in coordination with legal counsel,” O’Connor and Vogelmann wrote in another statement to Spark.

“For any decision that has the potential to expose the school district to liabilities, we always involve our legal counsel,” Vogelmann wrote. “When it comes to policymaking, our board’s number one priority is always to do what is in the best interest of all students and without compromising the district’s financial well-being, especially with regard to the law.”

While they won’t be creating a policy for transgender students, the district may, according to Vogelmann’s and O’Connor’s response, consider creating administrative guidelines addressing them instead.

“That work is not complete,” Vogelmann and O’Connor wrote. “We will continue our current practice of examining policies and guidelines to ensure that all students are always provided a safe and secure learning environment.”

A policy, according to Murray, is “a statement coming from the Board of Education voted on in public session,” while administrative guidelines are created and changed by the superintendent without any public process. According to Lakota Media & Community Relations Executive Director Lauren Boettcher, “the biggest difference is that guidelines do not require board approval.” All administrative guidelines, according to Boettcher and Murray, connect to existing policies.

“When an administrative guideline addresses a specific group of students, it’s because the policy itself is dictating that we do that,” Boettcher said. “So guidelines are really the interpretation of the policy, and it’s what directs the day-to-day operation and implementation of that policy.”

Administrative guidelines for transgender students could be connected to Lakota’s nondiscrimination and anti-harassment policies, according to Vogelmann’s and O’Connor’s response. Both policies include transgender students among the classes they protect but don’t list specific accommodations that must be made for them.

The two policies were modified to include transgender students in August 2015, according to Boettcher, when Neola, the legal organization that recommends policies to Lakota’s school board and other districts, suggested that they be added.

“There were numerous cases where federal enforcement agencies were treating transgender as a protected class,” Neola Associate for Lakota Norm Burkhardt told Spark. “We felt it was best for our clients to be in a position to add that to their protected class language.”

According to Boettcher, Lakota “relies on Neola totally, in addition to our legal counsel, to direct us with what is compliant with the law.”

“The last thing that a school district will do is go off the beaten path and create their own policy or modify a policy that’s been handed down to us from our legal counsel and our policy provider [Neola],” Boettcher said. “Because at that point we’re unprotected, and our responsibility is to protect the school district and to make sure we’re adhering to the law.”

Neola, according to Burkhardt, gets input for its policy recommendations from “federal agencies, state agencies, the state legislature, and requests from school districts about issues that need to be addressed.” The company has not created a policy for transgender students because there’s no clear protocol for what districts should legally do for them.

“If and when there’s a specific direction that is clear, we would consider providing that,” Burkhardt said. “But right now it’s not black and white. It’s not very clear what in every case is an appropriate accommodation.”

After being told that the district may consider making administrative guidelines instead of a policy, Linda said that she still wants the district to protect transgender students with a policy because she believes that “a guideline can be changed at the whim of the superintendent.” She’s especially concerned because the district will be selecting a new superintendent in March.

“I will continue to advocate,” Linda told Spark. “I’m not sure how just yet. I will probably see what the superintendent sets up and go from there.”

According to Ohio School Boards Association (OSBA) Director of Legal Services Sara Clark, “a handful of districts have passed policies that directly address transgender students.” But most have worked with students “on a case-by-case basis.”

Right now it is not black and white. It’s not very clear what in every case is an appropriate accommodation. -Norm Burkhardt, Neola Associate for Lakota

Lakota has utilized this approach; O’Connor and Vogelmann wrote that “should any student feel they need an accommodation due to privacy concerns, including restroom use, we will continue to follow our practice of working closely and in collaboration with the student and their parents or guardians to do what is in the best interest of all students, in regard to both safety and privacy.”

When transgender students were added to the protected classes in Lakota’s policies last August, the district’s legal counsel provided advice about how to accommodate them. The guidance was shared with all principals and counselors and has since been updated to reflect how the situation has changed. Murray said that he tried to codify this guidance with the policies he drafted.

According to East counselor Matt Rabold, counselors and administrators follow this advice when helping transgender students. The counselor may work with the student to develop a transition plan, “depending on where they are in the transition and what accommodations they might be seeking.”

“If somebody just wants to come and talk to me about what they’re experiencing, then a plan may not be necessary,” Rabold said. “But if it’s something that’s going to require use of a restroom or a locker room or if it impacts others we need to have a plan to discuss how that’s going to be achieved.”

East Principal Suzanna Davis said that some transgender students the school has worked with “don’t want anything to change, they just want a counselor or an administrator to know” while others have “had a very open and honest dialogue and they’ve made decisions about pronouns that we’ve supported by letting teachers know.”

Davis doesn’t think that supporting transgender students is “drastically different from [helping] other groups.” Instead, she said, accommodating them is “one piece of an overall student focus.”

“As society evolves, schools evolve,” Davis said. “We’ve dealt with students as they’ve brought it to our attention. We’ve had very meaningful and personal dialogue with them to make sure that we’re all on the same page. We’re all working toward what’s best for that student and what that student wants.”

Sarah and Murray estimate based off their personal interactions with families that there are at least 20 other transgender students in the district. Murray believes that “in every instance, the child has been accommodated.”

“I’m so proud of our teachers and the way they take care of our kids, all of our transgender kids.” Murray said. “They do wonderful things for them, they’re nurturing them, and they’re caring for them.”

He thinks that other Lakota officials are trying to keep their efforts to support transgender students “kind of on the down low,” and are therefore unwilling to go through the public process of creating a policy.

“Lakota’s been doing the right thing for a long time,” Murray said. “But they aren’t willing to tell people or the parents of transgender kids. Parents have to learn from other folks and through the grapevine.”

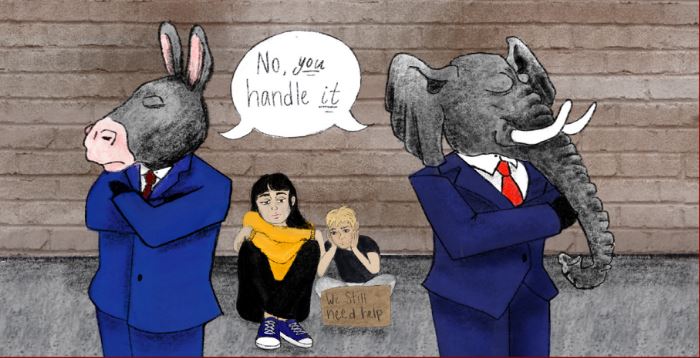

Controversy over Bathrooms

Murray believes that other district officials are reluctant to publicly discuss accommodating transgender students in part because they fear “backlash to the board.” Many oppose allowing transgender people to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity as opposed to the sex they were assigned at birth.

Of 116 East students surveyed, 28 percent said they would not support such a policy for Lakota. According to a 2016 Quinnipiac University Swing State Poll, 48 percent of Ohio voters said transgender people should not be allowed to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity.

Those opposed to allowing transgender people to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity often argue that doing so would put cisgender women at risk. Republican Ohio Representative John Becker, for example, wrote on his website that Target’s policy allowing transgender people to use the facilities that correspond with their gender identity “serves as an invitation to sexual predators to pose as transgender persons in order to gain easy access to a smorgasbord of women and young girls.”

“It started when Target became very public with their policy of open door bathrooms and dressing rooms,” Becker told Spark. “That concerned me as a public safety issue because that would make it an easy place for sexual predators to find victims.”

LGBT legal advocacy organization Equality Ohio Communications Director Grant Stancliff, however, said that “the kind of behavior people are afraid of, like somebody getting assaulted in a bathroom, is already illegal,” and that transgender people themselves are often the victims of harassment.

“A lot of times transgender people are the ones who experience violence, especially in places like bathrooms,” Stancliff said. “A lot of transgender people have to plan out their whole day around what bathrooms they know are safe, like a family bathroom or a single seater that locks.”

Before Alex came out, Linda would have wanted transgender people to use the bathroom that matches their assigned sex, but she said that “when your son comes and tells you he’s transgender, you’ve got to change how you think.”

“Three years ago I thought that I wouldn’t want a boy [who identifies as a girl] in the bathroom with my daughter, and it’s all changed,” Linda said. “I understand now that it’s not a boy going into the bathroom, it’s a girl going into the bathroom.”

She hopes that more people will also become educated about transgender children “so that they can understand that it’s not a freak, it’s not a kid who is confused, it’s a kid who is just in the wrong flipping body and it sucks to be that way.”

She, Sarah and Murray all said that they would want to accommodate those who may feel uncomfortable using the same bathroom as a transgender person. Linda invited other community members to join the conversation so that “we can figure out how to do things better, because I don’t want to shove things in people’s faces.”

She, Sarah and Murray all said that they would want to accommodate those who may feel uncomfortable using the same bathroom as a transgender person. Linda invited other community members to join the conversation so that “we can figure out how to do things better, because I don’t want to shove things in people’s faces.”

“There’s a judge in Ohio who said that all over the country schools have been making this work without losing control of any situation,” Murray said. “If a child is not comfortable going into the bathroom for fear of a transgender child coming in, we’ll make sure that they have the bathroom ready for them.”

Though her goal is for every student to be comfortable using the bathroom, Sarah believes that “policy has to be what is in the best interest of all students in a manner that is fair and transparent to all” and shouldn’t be stalled because of potential backlash from angry community members.

“When you’re talking about a civil rights issue, in the past that’s always happened,” Sarah said. “It doesn’t mean that it [would have been] the right thing in the 1960’s to continue to segregate black and white students. Social change comes slowly and with pain, and eventually people get on the right side of history.”

Troy City Schools, a district about 30 minutes north of Dayton, experienced such a backlash after it told families in 2015 that it had created guidelines allowing transgender students to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity.

“The community reaction was mixed,” Troy Superintendent Eric Herman told Spark in an email. “Many were confused about the issue. It is not an everyday topic for most people. It became very personal for many.”

Over 20 people, many of whom were angry about the issue, came to the first Troy school board meeting after the announcement was made. Alliance Defending Freedom, an “alliance-building, non-profit legal organization that advocates for the right of people to freely live out their faith,” sent Troy officials a letter urging them to reverse their decision.

The district didn’t change its position, however, and Herman, who gave a presentation on the subject at the Ohio School Boards Association Capital Conference this November, said that there are now no issues with transgender students in the district.

National and State Laws

Attention has been focused on transgender students only recently. Clark began receiving questions from districts about accommodating them two years ago; before then “it wasn’t a topic that was on many people’s radar.”

Ryan transitioned in the spring of 2015, according to Sarah, “before any of this made national news, and it was easier then because people made decisions based on this sweet little child, not based on what political retribution will there be if I do the right thing by this child.”

“The polarization started,” according to Murray, with a letter the Departments of Education and Justice sent to schools this May. It asserted that Title IX protections “encompass discrimination based on a student’s gender identity, including discrimination based on a student’s transgender status.”

Title IX prohibits discrimination based on sex in educational programs and activities that receive federal funding. According to The Ohio State University law professor Ruth Colker, it “has always required districts to offer different bathrooms to people of different sexes, but until recently had not defined how you decide what gender someone has.”

“As we started to have disagreements about how to respond to students who were requesting to use particular bathrooms, the Department of Education [and the Department of Justice] issued what is called ‘guidance,’” Colker said. “And in that guidance it said that school districts should allow students to use the bathroom that corresponds to the gender with which they self-identify.”

In October, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to rule on the issue in the case Gloucester County School Board v. Gavin Grimm. The justices’ decision, according to Clark, “will have national implications and will more clearly define the rights of students and the responsibilities of school districts in this area.”

Until the Supreme Court rules on the case, transgender people’s rights are still “an evolving area of the law,” according to Colker. She expects that “within ten years we’ll see federal legislation that protects people from gender identity discrimination.” Until then, however, politicians and activists on both sides of the issue are focusing on state and local governments.

Becker had worked on drafting a bill that, as he told Spark, would require “private businesses that have an open door bathroom policy to simply state that with a placard of some sort.” Becker did not introduce this bill because it lacked support from both the transgender and conservative communities. He also said, however, that other Republicans are planning to create another bill addressing the issue next year, though he declined to say what it would provide for.

Pro-LGBT groups in Ohio have been supporting House Bill 389, which would prohibit discrimination based on gender identity and sexual orientation. Without such a law in place, according to Stancliff, “in most parts of Ohio, LGBTQ people can be legally discriminated against.”

Currently, however, “it looks like only the Democrats [the minority party in Ohio’s state legislature] support it,” so advocates have been working to pass similar nondiscrimination laws at the local level. According to Stancliff, 15 Ohio cities have laws that protect people from discrimination based on gender identity, including Cincinnati, Cleveland and Columbus.

Most people have focused on the way these nondiscrimination laws would affect what restrooms transgender people can use because, according to Colker, “when anyone goes outside the home, they typically will find themselves at some point having to use the restroom.” But many transgender people face “enormous discrimination in pretty much every aspect of their lives.”

“The Stakes are Too High”

Many transgender students experience discrimination in the form of bullying or harassment at school. According to the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network’s (GLSEN) 2013 National School Climate Survey, approximately 38 percent of LGBT students reported feeling unsafe at school because of their gender expression, and about 33 percent said they heard negative remarks about transgender people at school.

In addition to struggling with bullying, many transgender children may be misgendered and find it difficult to get others to call them by their preferred name and pronouns.

“One of the main challenges would be passing and feeling affirmed in their gender,” Cincinnati Children’s Transgender Health Clinic Social Worker Sarah Painer said. “A lot of my patients might be misgendered by other people, be it in public or in school.”

The external challenges transgender students face often contribute to the internal discomfort with their body and biological sex many of them feel. According to Painer, “[gender dysphoria] can result in depression and anxiety, which would be a really normal thing for a lot of our patients to be experiencing.”

Gender dysphoria’s significant effects on a child’s mental health can, according to Sarah, “rob a child of their childhood.”

“Everything that regular kids do and enjoy, gender dysphoria robs children of that experience,” Sarah said. “Imagine waking up and having a complete disconnect with what you see in the mirror and having people look at you and have a confused look on their face because they don’t understand who you are.”

When he was in kindergarten and hadn’t socially transitioned but “expressed more masculine,” Ryan was forced out of the girls’ bathroom. He had anxiety, didn’t want to go to school or raise his hand in class, and ultimately wasn’t learning or progressing like his peers.

Ryan then began using the gender neutral family restroom on the other side of school, but “that became a problem as well” when other children started to question why he was going to the bathroom no one else used. So the kindergartener started not using the bathroom at school at all.

“That was a very sad time for us,” Sarah said. “It’s heartbreaking for a mom to see your kid, a child who’s been potty trained since they were two and never had accidents, get off the school bus and start running home as fast as they can with urine streaming down their leg.”

Though Ryan’s doing well now that he’s transitioned and is supported by his family and school, the psychological symptoms of gender dysphoria can have a profound effect on a person’s mental health. According to a 2014 report by the Williams Institute and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 41 percent of transgender people have attempted suicide, almost 10 times higher than the rate for all U.S. citizens.

Linda knows how difficult school can be for transgender students and said that she doesn’t want “any parent to have to have added burdens if I can make a difference.” She wants Lakota to ensure their rights because “the stakes are too high, much too high” for the district to take any risks with supporting them.

“There’s over 500 kids in the Transgender Clinic in Children’s,” Linda said. “I see these little four and six year old kids and I think ‘oh my gosh, if they can grow up being accepted they’re not going to have the anxiety, they’re not going to have the depression, they’re not going to have the suicide attempts. Any parent wants that.’”

This story originally appeared in the December issue of Spark.