Story by Erinn Aulfinger | Photography Used with Permission

His hands were a roadmap.

Paved with memories and freckled with love and laughter. He was a strong man that lived his life as a business owner, loving husband, father and grandfather.

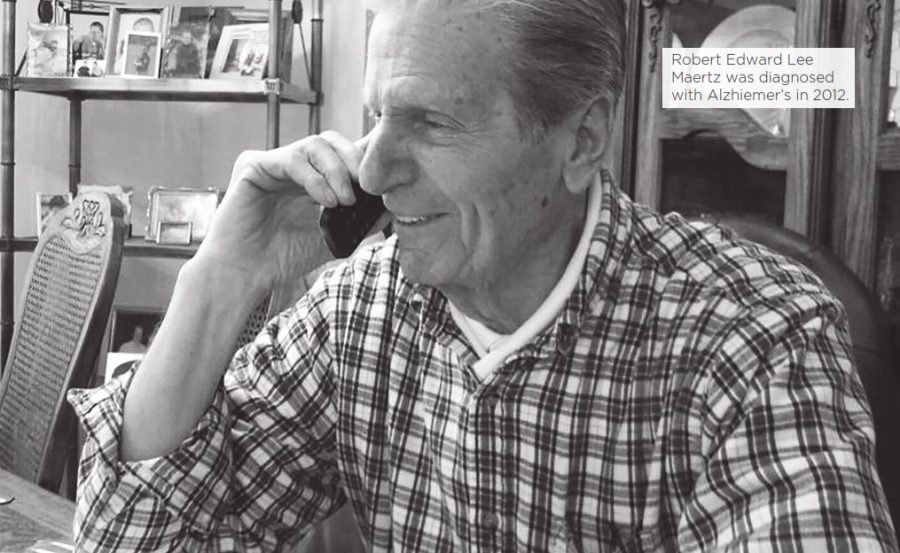

Lakota East junior Leah Boehner recalls holding her grandfather’s hand to keep him grounded throughout his battle with Alzheimer’s Disease.

“I always held his hand,” says Leah. “Especially in the later stages, that’s all you could do. When he came back from [spending time in the Good Samaritan Hospital Psychiatric Ward, there] was just a world of a difference [in his personality]. His head was down and he wasn’t looking at anyone. He had this cup of coffee and was just staring at it and I lost it. I had to [leave the living room] bawling my eyes out. From then on, all I could do was hold his hand.”

Despite not being officially diagnosed until November 2012, Leah’s mother, Dena Boehner says she and her father, Robert Edward Lee Maertz, knew something was wrong when he began to obsess over his finances, and forgot how to get into his online banking account, something he had done regularly as a business owner. Maertz also started confusing Dena’s sister with his wife, who had passed away ten years earlier. They had previously taken him to a neurologist, who had passed off the problems as “old age” and told them to return in a year. They returned later to the family doctor, a friendly man who did not stress out her father as much, and he confirmed a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

According to a 2016 study by the Alzheimer’s Association, 5.3 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease. However, as the baby boom generation reaches age 65 and older, the age range with the greatest risk of Alzheimer’s is expected to increase. By 2050, the number of people age 65 and older with Alzheimer’s disease is expected to triple to 13.8 million. Estimates based on U.S. Census high range projections of population growth predict upwards of 16 million newly diagnosed citizens.

Jessica Alber, a postdoctoral fellow and rising faculty member in Alzheimer’s research at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, says that while Alzheimer’s used to be referred to as merely ‘hardening of the arteries’ or ‘senility,’ it can be more accurately diagnosed in the 20th century.

“Currently, clinicians diagnose ‘probable [Alzheimer’s disease]’, and diagnosis can only be confirmed at autopsy,” Albert tells Spark. “However, the development of new brain imaging techniques has allowed for the assessment of the two characteristic proteins, amyloid and tau, in living humans, which provides us a lot more information about the specific diagnosis.”

In 1901, Alois Alzheimer studied the first known case of Alzheimer’s in which a 51-year-old woman named Auguste had symptoms of confusion and irritability. Her autopsy five years later led him to believe these symptoms were a result of plaque and tangles in her brain. It was not until 1976 that Robert Katzman, a San Diego neurologist, termed the phrase Alzheimer’s Disease and suggested it was not a normal part of aging.

Alber says the lack of clarity around Alzheimer’s diagnosis stems from the differentiation of symptoms amongst patients including, but not limited to: memory loss, difficulty finding the correct word, or keeping track of time. This variety in symptoms, she says, reinforces that the disease is not limited to one distinct cause.

Professor of Neurology and Neurobiology and Behavior at the University of California, Irvine, Claudia Kawas says Alzheimer’s disease can develop from a combination of factors.

“I think people always want [Alzheimer’s] to be [caused] by one thing and it’s never one thing,” says Kawas. “All of human biology has to do with what we bring to the table genetically and [our] environment and experiences. We find all these [factors] are relevant. If you have a family history of Dementia or Alzheimer’s disease your risk is increased, but not as much as people think. About 60 percent of those who develop Alzheimer’s don’t have a family history.”

As a result of the disease’s nebulous origin, Alzheimer’s patients and families often face difficulties dealing with their diagnosis. Director of Communications and Public Policy at the Alzheimer’s Association of Greater Cincinnati Steve Olding says the Association provides local support for patients and their families free of charge.

“We work hand in hand with the family caregivers [to help create] short term and long term plans in dealing with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s is unique in the fact that there is not a real particular time frame [for the disease]. For some individuals, it might be five years from the point of having problems with memory to the point of needing a nursing home. In other cases it might take 15 years,” says Olding. “Around here, we say if you’ve seen one case of Alzheimer’s disease, you have seen one case, because it affects the individual and the family dynamic differently.”

For Dena, watching her father’s Alzheimer’s progress was painful for both of them. Usually independent and active, Maertz had to stop daily activities like driving after a few minor accidents. Dena says Maertz began to struggle to remember words and she would have to divert this frustration by allowing him to feel helpful with small tasks.

“[I had to] let him feel helpful still. He was a strong independent man, he owned his own business and he was a hard worker, so he felt like he had nothing anymore,” says Dena. “Even if it was something simple like folding laundry, I would say ‘Dad I really need your help.’ He just wanted to feel like he was useful.”

Early Stage Program Coordinator for the Alzheimer’s Association of Greater Cincinnati Shannon Braun primarily works with people that are newly diagnosed or in the early stages of the disease, which is defined as the person being aware of their diagnosis. She says one of the biggest challenges across the board is stopping driving for those affected due to their ability to get lost as well as their slower reaction times.

“[Driving] is such a key part of our independence,” says Braun. “Most people as they age naturally limit their own driving, but when it’s Alzheimer’s that’s making you change those plans, it seems more sudden, like you are not ready to stop driving yet.”

Like Dena, approximately two-thirds of caregivers are women, according to the 2014 Alzheimer’s Association Women and Alzheimer’s Poll. Women were reported to spend 102 hours hours a month caregiving compared to 80 hours provided by men. Of caregivers, women were more likely to experience higher levels of burden, depression and impaired health health than their male counterparts, which is thought to arise because females tend to spend more time caregiving, take on more caregiving tasks, and are more likely to care for someone with a greater number of behavioral problems.

According to Alzheimer’s Disease International, more than 40 percent of family caregivers rate the emotional stress of their role as high or very high. Dena says she had to become a “mother figure” to her father after his diagnosis.

“We totally switched roles. He was now the scared, insecure child that needed his every move watched, and I was in the position of making sure he was taken care of properly and making sure all of his needs were met,” says Dena. “When I was growing up, my dad always took care of us. He was the person we went to if we needed help, and then we had to make every decision for him.”

Braun accredits the “loss of the person” as the most difficult aspect of the disease for caregivers. She says it is lonely and isolating to have to make decisions for a spouse or loved one who typically would have helped to make these decisions.

“It’s a grieving process, and just when they think they’ve gotten the hang of it, it’s a progressive disease so it continues to change and decline,” says Braun. “They never feel like they’re on top of [the disease]. They are always scrambling. They are grieving a loss, while also trying to hit a moving target. It’s very overwhelming and all consuming.”

Olding says the case-by-case structure of the disease makes it challenging because every caregiver is different in regard to dealing with its emotional and psychological stress.

“It’s one thing to be taking care of a loved one with cancer [in which] you are taking care of that individual, but there is still that connection in regards to them knowing you,” says Olding. “It’s much tougher for an Alzheimer’s caregiver where, after a certain amount of time, your loved one may not recognize you anymore or be able to call you by name.”

According to Olding, the most difficult thing for the caregivers, apart from the shock of the initial diagnosis, is when the affected person no longer recognizes the caregiver. The Alzheimer’s Association offers suggestions to help relieve the stress of caregivers and their families by providing information on what they can expect in the future, and recommending support groups and education.

Although he often could not place Dena and Leah specifically, Maertz was always happy to see them, Dena asserts.

“He recognized us until the end and you could tell even without him speaking,” says Dena. “Sometimes I would be there for 45 minutes with zero eye contact and all of a sudden he would look at me and his eyes would light up and he would say ‘its you.’ Even if he couldn’t say it, his face [spoke] and he would bring up my hand and hold it to his chest.”

When determining whether a person should be cared for by the family in the home or placed in a facility, Braun says it depends on the family and their personal abilities and resources to care for the affected person. She says even though she encourages people to stay home as long as they feel comfortable taking care of their loved one, she recommends applying to facilities as a “plan B,” as they often have waitlists in the Cincinnati area.

After taking him out of one facility, Dena and her sister purchased an apartment and home care to provide personal care for their father. This soon became dangerous as it was difficult to keep him in. They then placed him in another facility which was strictly an Alzheimer’s and Dementia unit. Dena says they were able to keep the patients safely secured in the building, but the education of the workers was unsatisfactory and the family “definitely (wasn’t) comfortable with the people that were caring for him.”

“[The patients] are scared. Strangers are coming at them and trying to make them take a shower and change their clothes,” Dena says. “They still have their feelings [and] they still get embarrassed and here’s this strange young girl coming in trying to make them get in the shower. It is just very confusing to them.”

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the national average cost for basic services in an assisted living facility is $43,539 per year. In contrast, the average cost for a room in a nursing home is $92,378 per year for a private room and $82,125 per year for a semi-private room. For Dena, the facilities her father was placed in cost $3,000 and $3,800 a month, respectively, while home care cost between $10,000 to $12,000 a month.

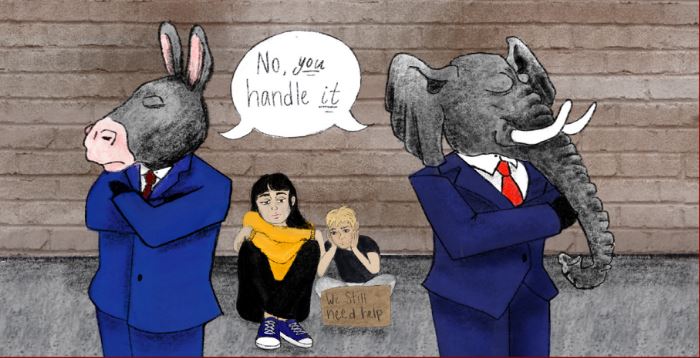

Aside from family-incurred costs, according to a 2017 study by the Alzheimer’s Association, the direct costs to American society of caring for those with Alzheimer’s and other dementias will total an estimated $259 billion as more people age and the incidence of the disease grows. Medicare and Medicaid will spend an estimated $175 billion caring for those with Alzheimer’s and other dementias, which is 68 percent of total Medicare costs.

Olding says one out of five Medicaid dollars are currently spent on someone with Alzheimer’s, which makes it the costliest disease in the U.S., outpacing cancer, diabetes and heart disease in terms of costs to society.

In 2012, former President Barack Obama created the National Alzheimer’s Project Act, which plans to prevent and eradicate the disease by coordinating efforts throughout the U.S. by 2025.

According to Alber, if a preventative medication is not found, “we [will] face a public health crisis, [because] we simply do not have the infrastructure to support this generation.”

“It is important for us to develop disease modifying treatments that can be administered prior to the onset of symptoms, and slow or eliminate the manifestation of the disease,” Alber says. “I believe the cure will not be a magic bullet, but instead we will see a variety of therapies, that when taken in combination, will help to reduce risk or to slow the progression of the disease, similar to the ‘AIDS cocktail’ in the 1990s.”

Alber says this effort for eradicating the disease will require a collaborative effort from all people.

“Alzheimer’s is a global responsibility and a cure will require the cooperation of scientists, clinicians, politicians, pharmaceutical companies, and communities at large,” Alber says. “The fight against Alzheimer’s requires participation from all people: from individuals who have a diagnosis to individuals without any symptoms.”

University of Pennsylvania Professor of Medicine, Medical Ethics and Health Policy, and Neurology Jason Karlawish says he is currently working on treatment and prevention studies to look deeper into eradicating Alzheimer’s.

Currently, he is targeting the “pathological cascade” that leads up to the buildup of amyloid plaque in the brain which is one of the pathologic hallmarks of alzheimer’s disease. This cascade, he describes, consists of stereotypical events that unfold in the brain that transform a brain from being healthy to being diseased. He says they can currently see the steps that lead up to transforming healthy amyloids into the plaques, and are targeting drugs to prohibit these events from taking place in the future.

Two years after her Maertz’s official diagnosis, Dena and her family were informed by doctors that her father would not live much longer. Leah says she only saw him once during his final days, not speaking but just holding his hand. Dena did not leave his side apart from coming home for two hours to sleep and bathing twice. She says she stayed by his side and “then just waited for it to be over.”

“I have mixed emotions about the last week [before he passed away,] because it had been such an awful two years [and] I wanted him to be done. I knew he was suffering and I prayed that he wouldn’t have to do this for much longer,” says Dena. “Watching this strong independent man wither away to a baby, don’t get me wrong, I was sad, but I was [also] like ‘thank you, God, please take him, he does not want to do this anymore.’”