Your donation will support the student journalists of Lakota East High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs!

OpinionEmbryonic stem cell research can save lives, however there are an abundance of ethical concerns regarding the explorative research.

OpinionEmbryonic stem cell research can save lives, however there are an abundance of ethical concerns regarding the explorative research.Elizabeth Vernon, Staff Writer | May 1, 2025

Movie ReviewsSci-fi thriller “Companion” combines rom-com clichés with gory horror to create a complex, comedic, and captivating film.

Movie ReviewsSci-fi thriller “Companion” combines rom-com clichés with gory horror to create a complex, comedic, and captivating film.Joselyn Duff, Opinion Editor | April 30, 2025

Ultimate FrisbeeEast freshman Isadore McCune plays Ultimate Frisbee at William Mason High School due to the absence of a team at East.

Ultimate FrisbeeEast freshman Isadore McCune plays Ultimate Frisbee at William Mason High School due to the absence of a team at East.Gwen Gilbert, Sports Editor | April 29, 2025

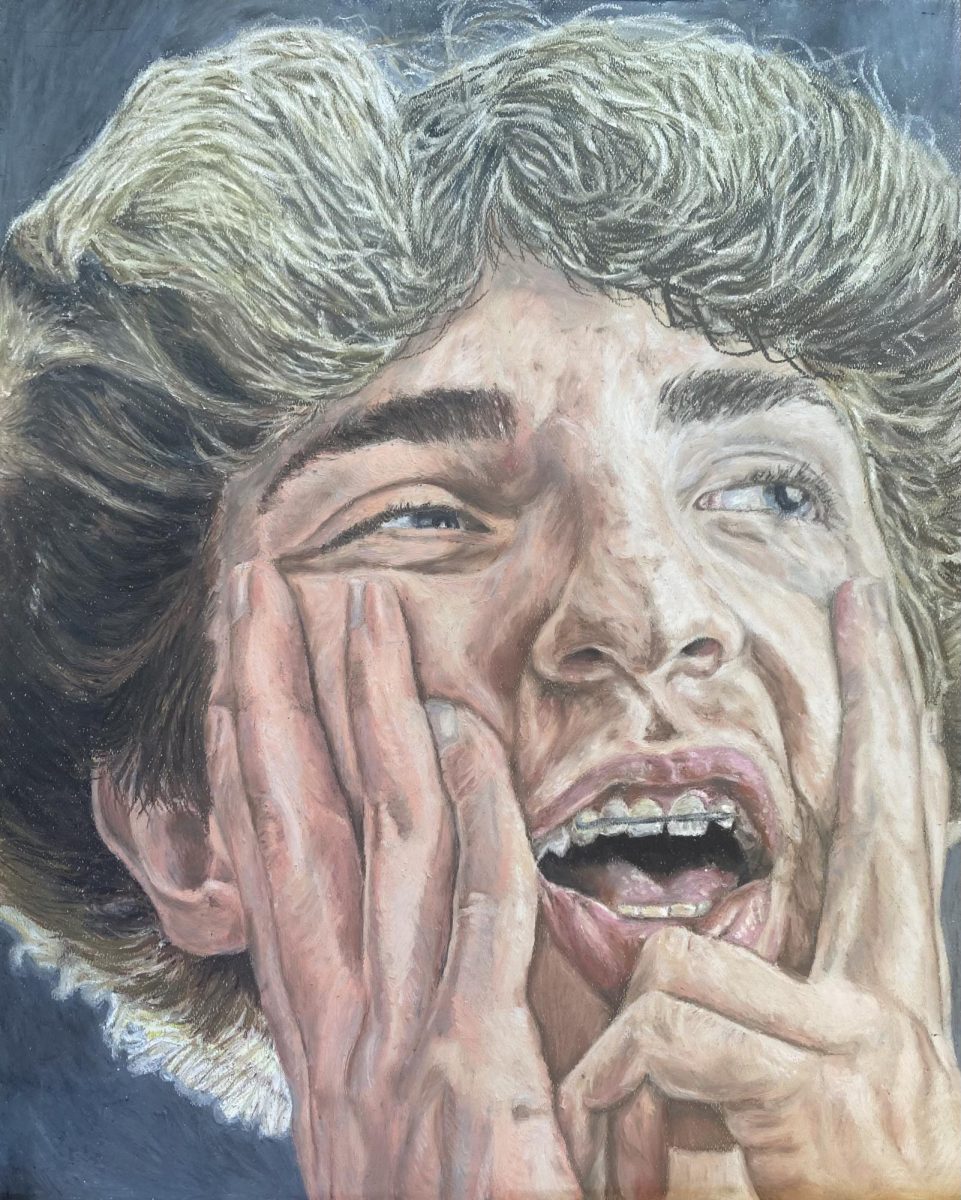

FeatureEast seniors Kaya and Kenzie Lamb share the behind the scenes of being identical twins, while their best friend Hailey Isacson comments on their inseparable relationship.

FeatureEast seniors Kaya and Kenzie Lamb share the behind the scenes of being identical twins, while their best friend Hailey Isacson comments on their inseparable relationship.Sophie Schaller, Feature Editor | April 28, 2025

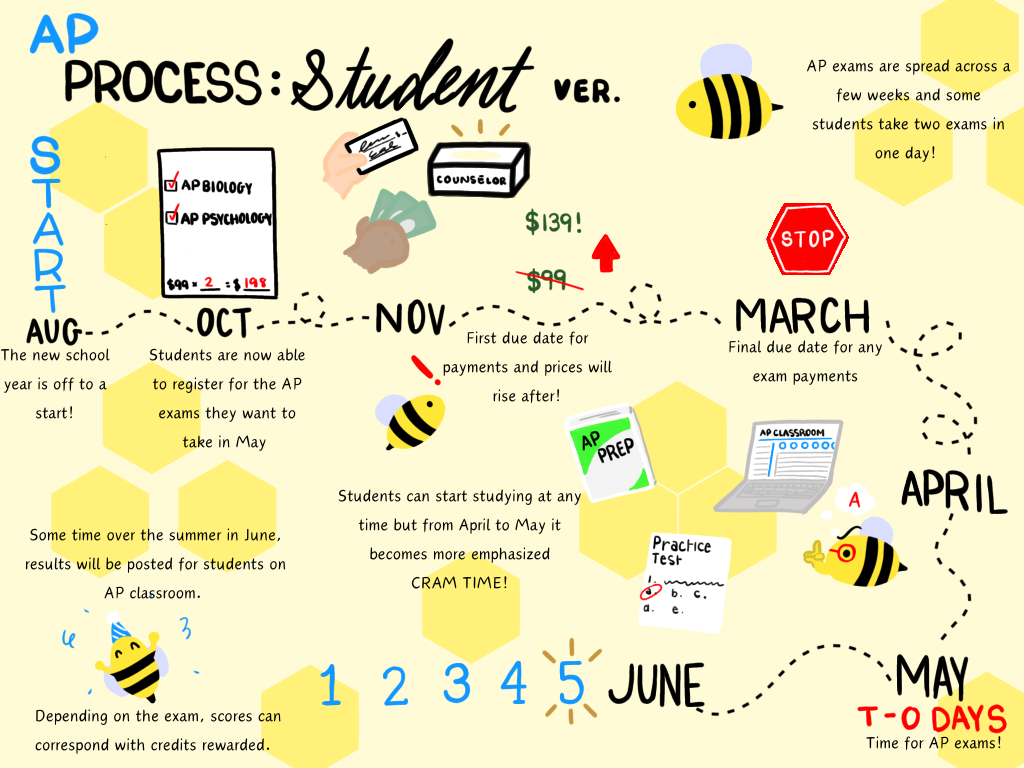

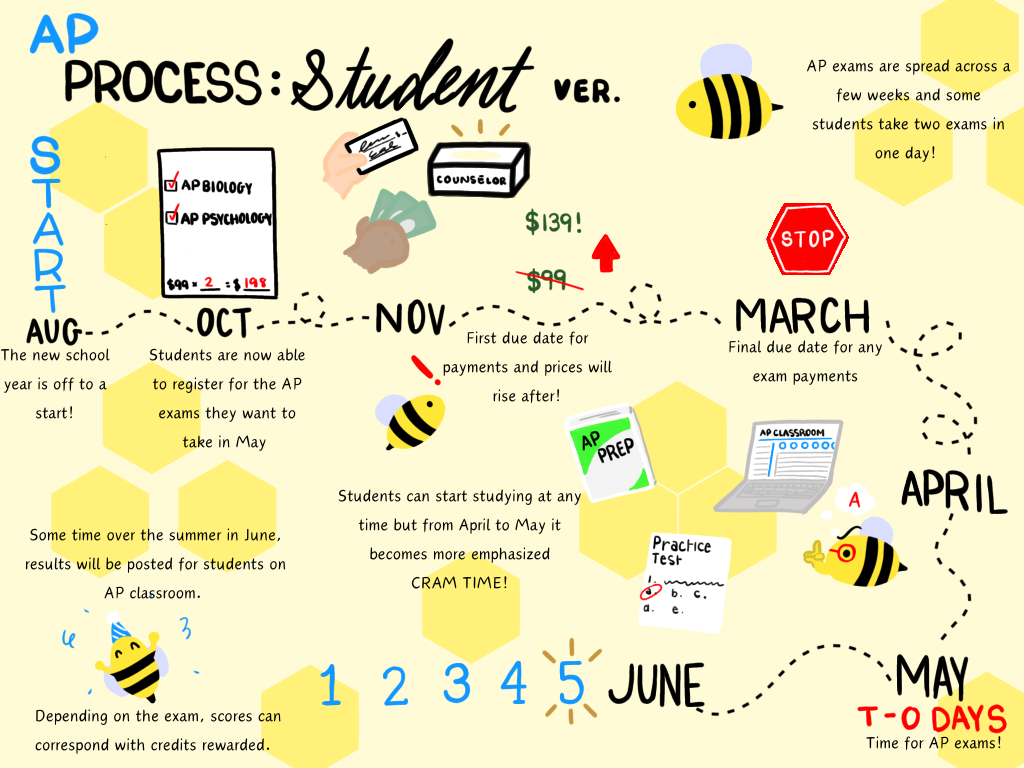

NewsWith the AP test registration date set in October students have expressed concerns about not knowing how they will do on the test before registering.

NewsWith the AP test registration date set in October students have expressed concerns about not knowing how they will do on the test before registering.Yen-Nhi Bui, Staff Writer | April 27, 2025

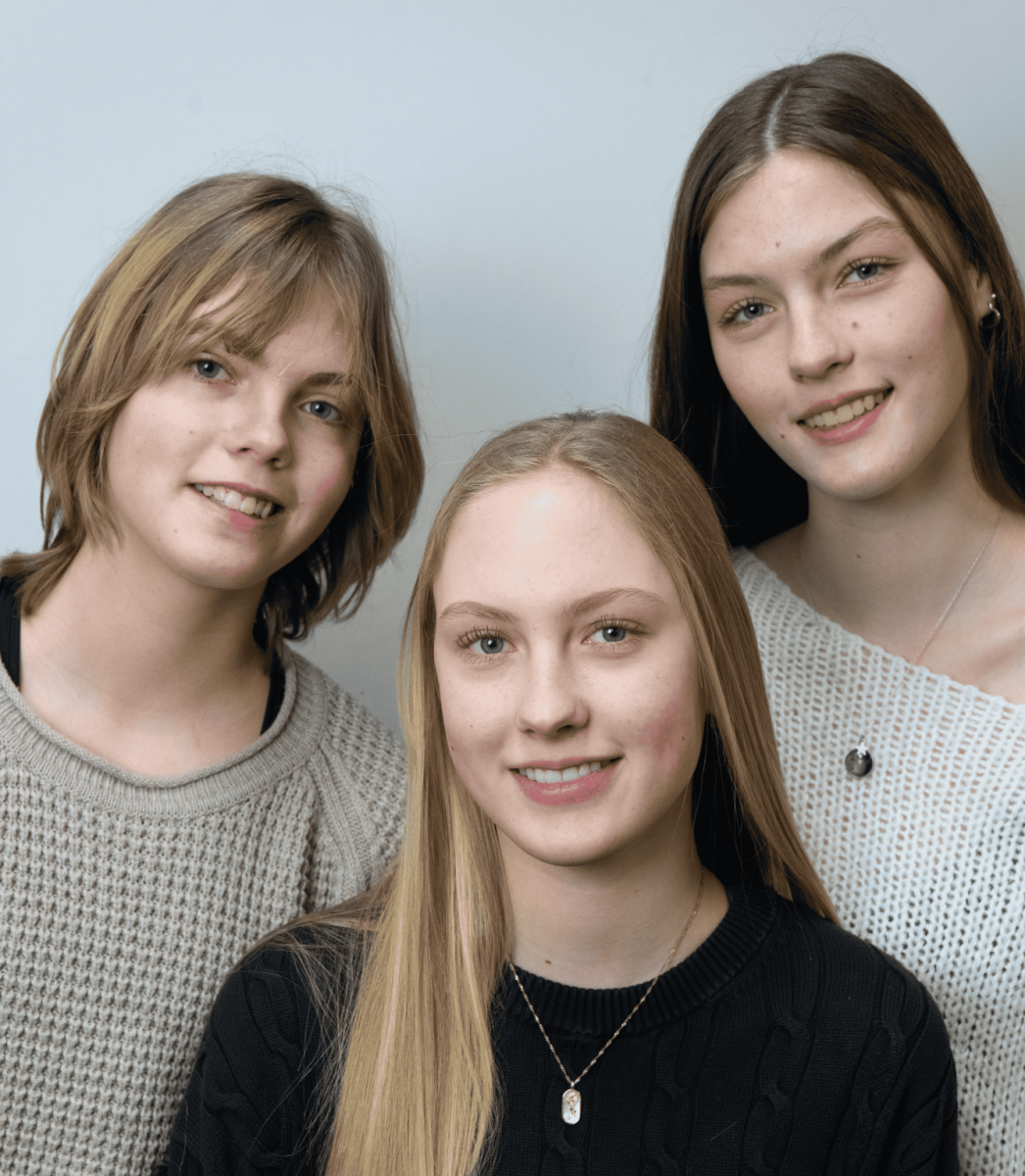

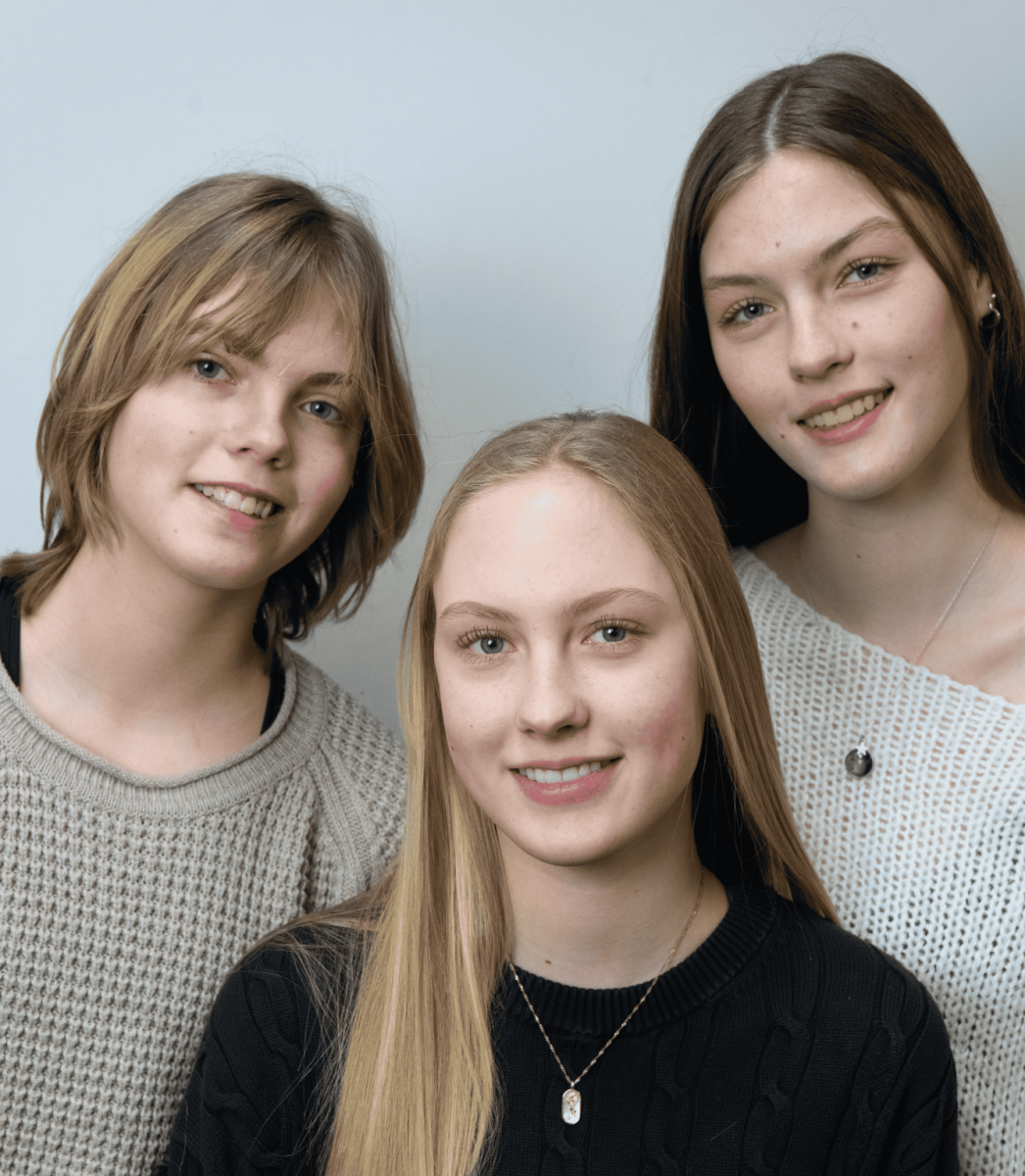

FeatureIzzie Tenhundfeld, the oldest of the triplets, shares her expereinces of being in a trio, while also finding what sets her apart.

FeatureIzzie Tenhundfeld, the oldest of the triplets, shares her expereinces of being in a trio, while also finding what sets her apart.Madison Cline, Staff Writer | April 21, 2025

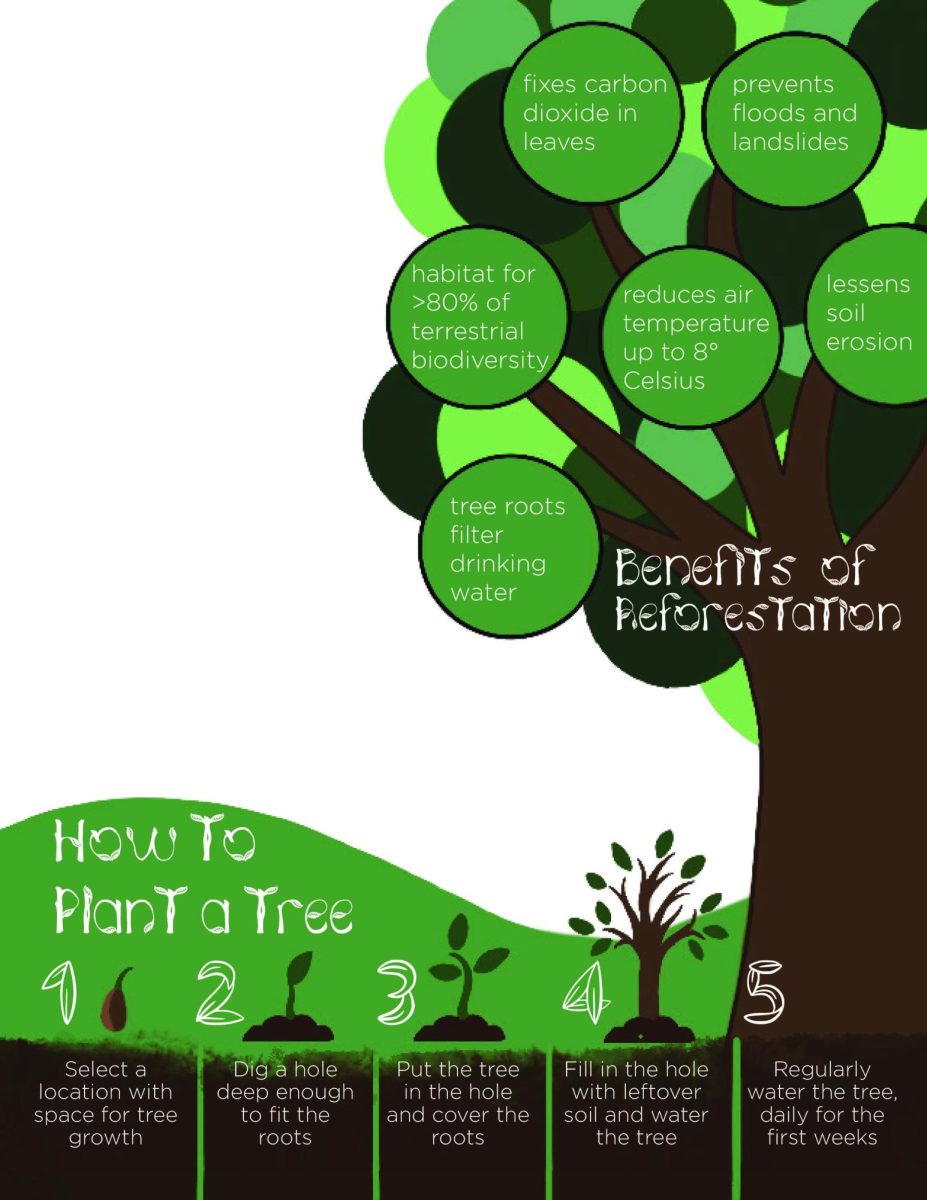

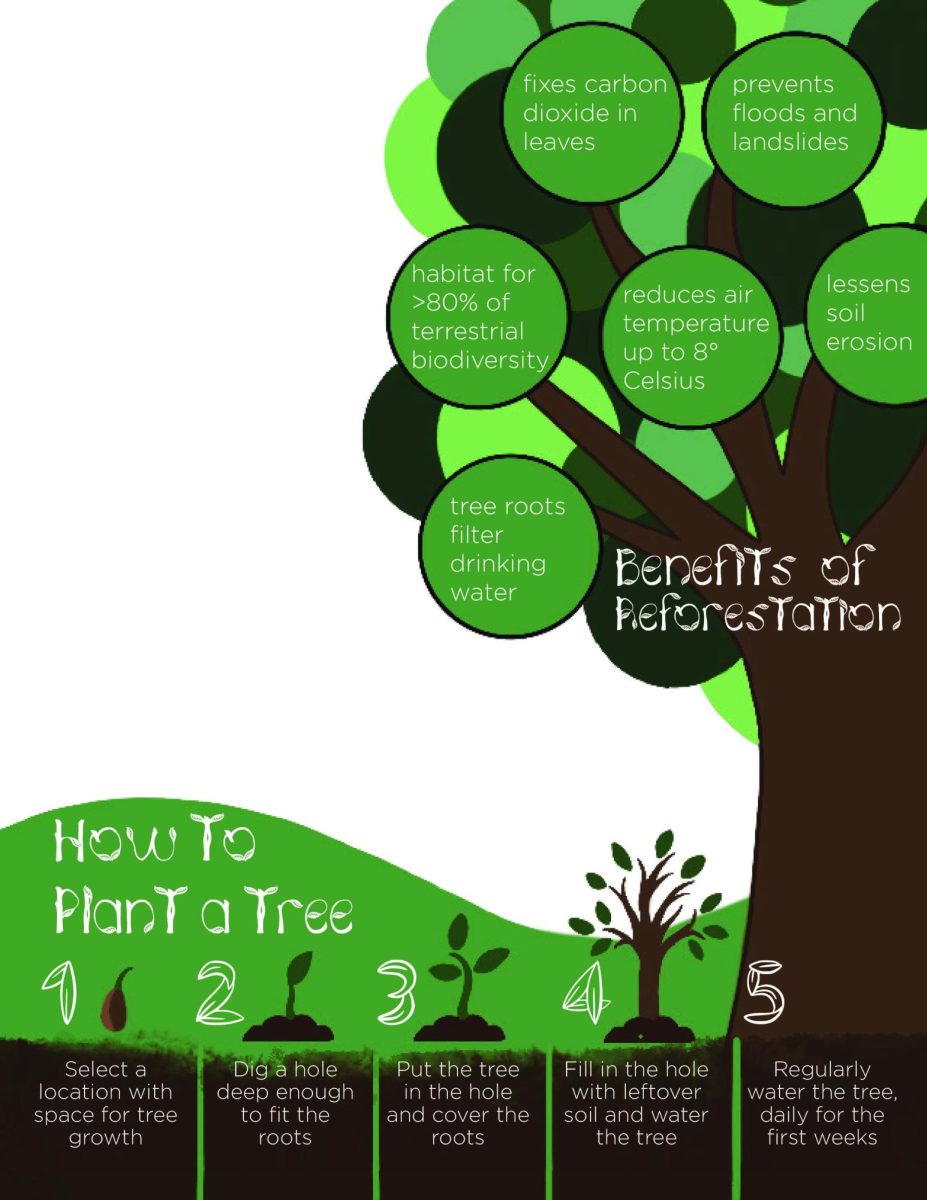

NewsA reforestation area created by East Environmental Science teacher Mark Folta and student volunteers has been established as a Certified Wildlife Habitat, through the National Wildlife Foundation.

NewsA reforestation area created by East Environmental Science teacher Mark Folta and student volunteers has been established as a Certified Wildlife Habitat, through the National Wildlife Foundation.Grace Callahan, Editor-in-Chief | April 20, 2025

FeatureCaitlyn Tenhundfeld falls in the middle of her sisters. She acts as a calm presence and prioritizes her family as well as her independence.

FeatureCaitlyn Tenhundfeld falls in the middle of her sisters. She acts as a calm presence and prioritizes her family as well as her independence.Maci Brent, Staff Writer | April 14, 2025

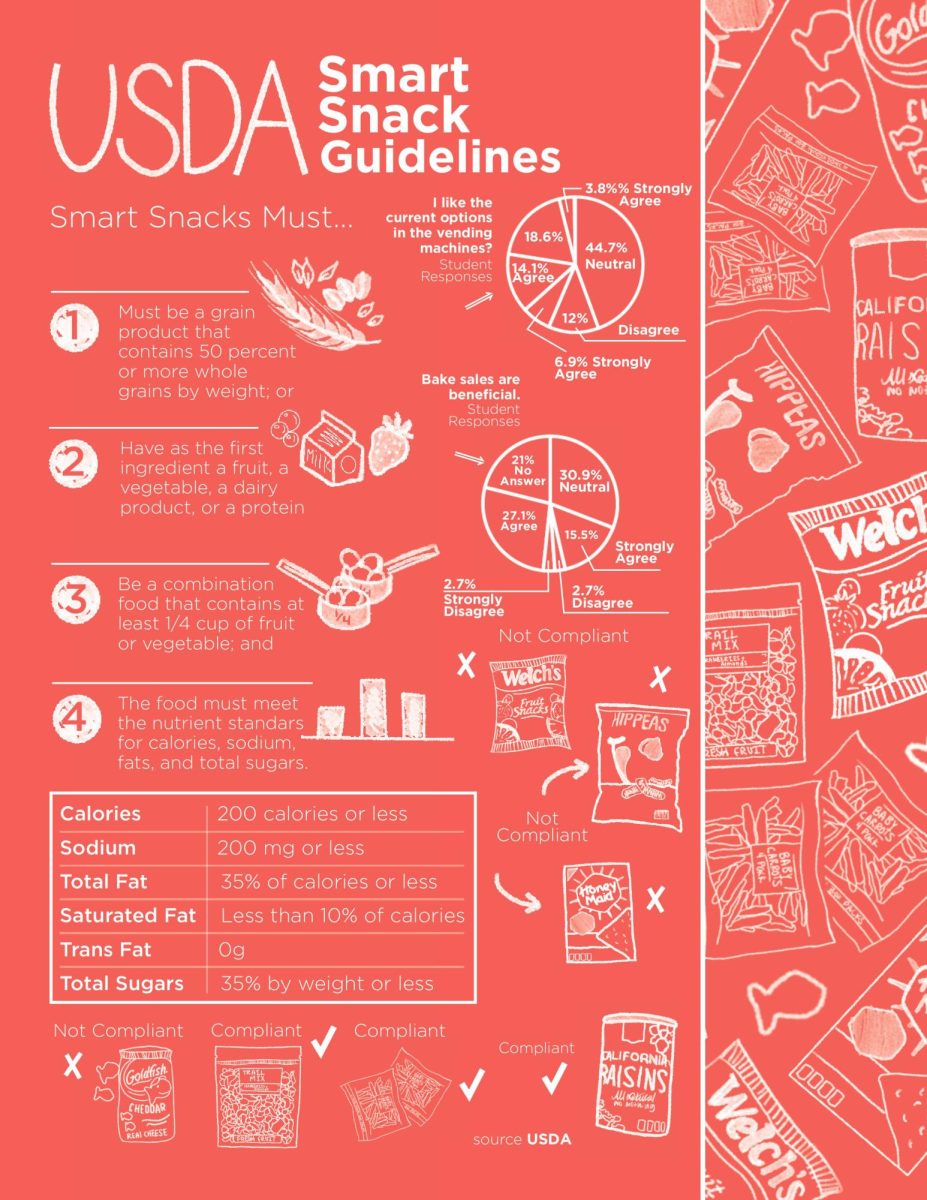

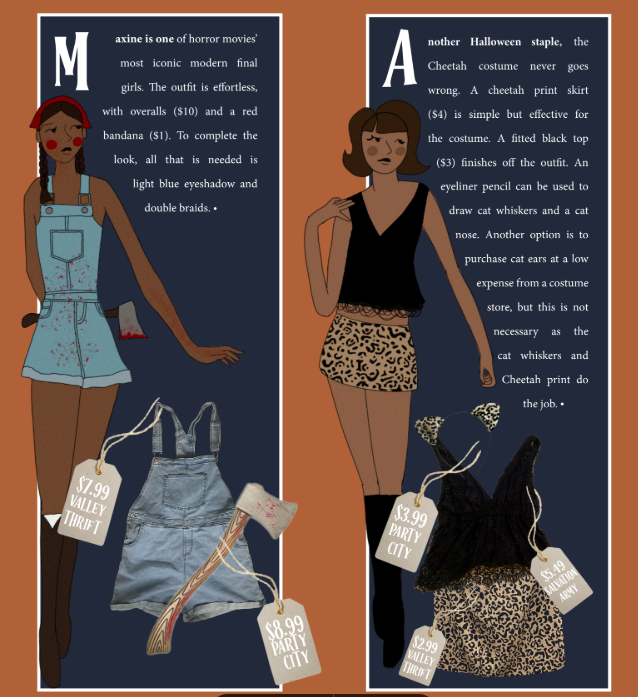

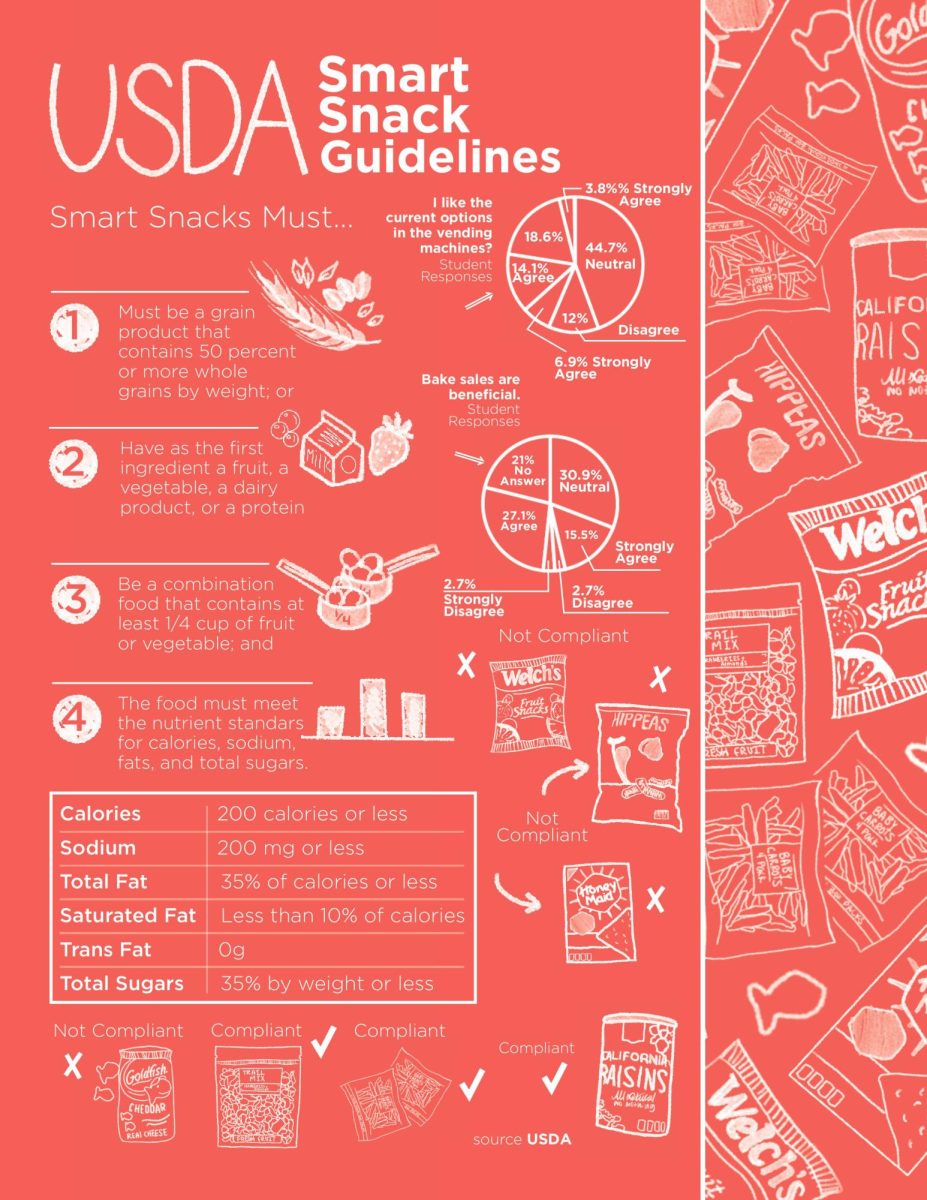

NewsDue to changes in the USDA “Smart Snack“ policies, Lakota has made adjustments to their policies regarding bake sales.These changes have club leaders concerned regarding future fundraising efforts.

NewsDue to changes in the USDA “Smart Snack“ policies, Lakota has made adjustments to their policies regarding bake sales.These changes have club leaders concerned regarding future fundraising efforts.Sophie Schaller, Feature Editor | April 13, 2025

OpinionPresident Trump’s proposed tariffs could do more harm than good to the U.S. economy.

OpinionPresident Trump’s proposed tariffs could do more harm than good to the U.S. economy.Ashley Skinner, In-Depth Editor | April 10, 2025

Music ReviewsOn Mar. 28, 2025, Ariana Grande returns to “Eternal Sunshine” with a deluxe version that includes six more songs and a short film.

Music ReviewsOn Mar. 28, 2025, Ariana Grande returns to “Eternal Sunshine” with a deluxe version that includes six more songs and a short film.Alex Schwind, Culture & Graphics Editor | April 2, 2025

FeatureEast seniors and triplets Sammi, Izzie, and Caitlyn Tenhundfeld spend all of their time together. Sammi, the youngest of the girls, set the trend of doing colorguard together.

FeatureEast seniors and triplets Sammi, Izzie, and Caitlyn Tenhundfeld spend all of their time together. Sammi, the youngest of the girls, set the trend of doing colorguard together.Sara McGuire, Staff Writer | March 31, 2025

NewsAfter the resignation of Rob Burnside Matt MacFarlane has been named the interim principal of Lakota East High School for the remainder of the school year.

NewsAfter the resignation of Rob Burnside Matt MacFarlane has been named the interim principal of Lakota East High School for the remainder of the school year.Luke Viviano, News Editor & Business Manager | March 30, 2025

Editorial BoardsThe editorial board voted 13-0 that social media is negatively affecting youth.

Editorial BoardsThe editorial board voted 13-0 that social media is negatively affecting youth.Spark Staff | March 27, 2025

Music ReviewsMac Miller’s eighth studio album Balloonerism was released on January 17, 2025.

Music ReviewsMac Miller’s eighth studio album Balloonerism was released on January 17, 2025.Elliana Celis, Staff Writer | March 26, 2025

SportsEast invests in a four-part projector setup in the gymnasium to light up the court and the atmosphere.

SportsEast invests in a four-part projector setup in the gymnasium to light up the court and the atmosphere.Elizabeth Vernon, Staff Writer | March 25, 2025

OpinionHelp is help, it doesn’t matter if it’s forced or voluntary.

OpinionHelp is help, it doesn’t matter if it’s forced or voluntary.Max Earl, Sports Associate Editor | March 21, 2025

View this profile on InstagramLakota Spark (@lakotaspark) • Instagram photos and videos