The Kids Are Not Alright

Spark explores the acts of, reasons behind, and solutions to public disruption from teens and young adults in the area.

Her phone rang again. On her day off, Zumiez Liberty Center Store Manager Ash George did not expect so many calls from work. She knew it was one of her staff members calling again, but she could not have imagined what they were about to tell her.

“[The mall] wasn’t feeling like a safe place for people to shop or enjoy themselves, and something had to be done,” George told Spark. “Management wasn’t really doing it fast enough, so I did what I could to force their hand.”

George petitioned to increase policy at Liberty Center in hopes of curbing youth disruptions, leading the mall to implement their curfew for minors, who are not allowed to be in the mall after 6 p.m. without an adult over the age of 21.

She said that the frequency of fights at Liberty Center had been becoming increasingly worse leading up to this incident. This fight in particular had forced her store to close early, and inspired her petition.

“There was a big riot of at least 100 people fighting down by the elevator, and security got jumped, with some of them being hospitalized,” said George.

This is a common sight according to a Spark survey of 50 stores at Liberty Center, with 67.3% of store representatives who that said they had experienced violence and/or outbursts from teens in or around their establishments.

On a larger scale, non-profit organizations like the National Urban League (NUL), Cincinnati Center City Development Corp. (3CDC), and Talbert House are fighting to combat youth disturbances in public places like downtown Cincinnati.

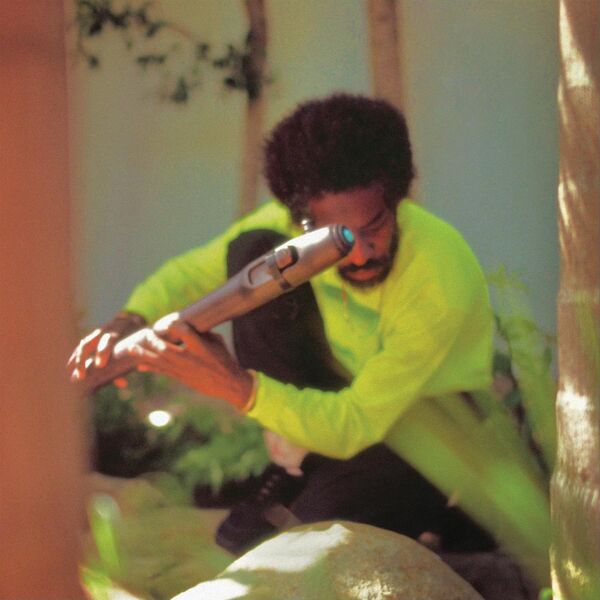

“Most of them are sudden disputes, which means that the intention may not have been to come and do something that day, but something happens in that space to where there’s disrespect, and then all of a sudden you have an incident,” NUL community outreach advocate Derrick Rogers told Spark. “That’s a lot of what we’ve seen on Government Square.”

In February 2024, a series of disputes among youth in Government Square in downtown Cincinnati sparked the attention of activist Iris Roley and other groups that aim to support teens who need it.

The NUL and other non-profits built relationships with teens downtown and offered them summer jobs and programs to keep them busy when school is not in session.

According to Rogers, members of the NUL were also downtown Mondays through Fridays, from February 1 to May 31 of 2023, during the school year to provide aid to kids and teens.

Aside from this physical fighting, the NUL and other non-profits downtown aim to reduce youth violence, even to the level of homicide.

“I had a cousin who was like a brother to me; he was gunned down and was a victim of gun violence,” said Rogers. “That struck me near and dear to my heart. Doing this type of work, and just seeing all the mothers and fathers that go through the pain of losing a loved one has kind of inspired me to continue this work.”

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), each year there are over 176,000 homicides among youth 15–29 years of age, making up 37% of the number of homicides each year globally.

“The overall goal of the [NUL] is really to get rid of or eliminate generational poverty within the minority communities and those communities that have been having a problem with generational poverty for a long time in the city of Cincinnati,” Rogers said.

Homicide is the third leading cause of death for people aged 10-24, and the leading cause of death for African American youth, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Closer to East, physical fighting remains a problem where George works and other public places.

According to the Spark student survey, 77.4% of the 237 students surveyed said that they had seen a fight in public before, and 87.7% of students said that they had seen a fight in school.

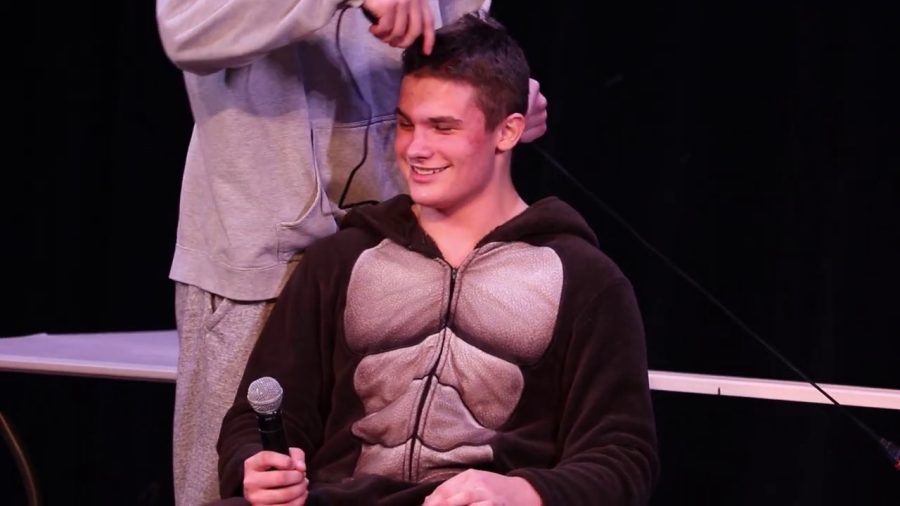

Similarly to George, Deputy Batdorf has seen public fights and other disruptions at Liberty Center among other places near East.

“It tends to be junior high kids and those in the early years of high school,” Batdorf told Spark. “They are kind of living in their own little world and really doing whatever they please.”

The first thing to be done when faced with a public fight would be to separate the two teens, then contact their parents or guardians, according to Batdorf. After that, the property manager of wherever the physical fight took place will usually want to take action, such as barring the offenders from the property.

Teens then contact their parents or guardians, according to Batdorf. After that, the property manager of wherever the physical fight took place will usually want to take action, such as barring the offenders from the property.

With new standards in place for minors at Liberty Center, Kings Island, and numerous other public spaces, the effectiveness of the policies have come into question by some of those working there.

53.1% of store representatives surveyed in the Spark survey of 50 stores at Liberty Center said that the policies put into place were ineffective.

“A lot of minors don’t care about the rules at all, but honestly, it is up to security to hold people to those rules,” said George. “If I have kids in here being crazy, and if they want to start wilding out and they’re not trying to listen to me, then it’s like: ‘here are the rules, and I can have you removed from the premises.”

While George sees the effectiveness of the new policies, she said it was more about the character of the teens themselves than the policies in place when preventing youth outbursts.

“Rules only do so much. It’s a piece of paper that tells you what you can’t do, and I hate to say it, but nobody likes being told what to do. So, it’s only gonna be effective for kids that are afraid of the repercussions,” said George. “If somebody is instilling morals in you, the rules are already what you agree with, or something that you at least can wrap your head around.”

According to Batdorf and George, fighting and other youth outbursts have decreased since Liberty Center enacted their new minor curfew.

“The general public and [law enforcement] are not babysitters. We are here to protect life and property, not babysit kids,” said Batdorf. “I would say parents need to be more on-top of their kids and aware of what they are doing or what they are going to do.”

What Batdorf calls a “general disrespect for the public,” can also be translated into schools. East AP US History and CP American History teacher Samantha Miller said that there are discrepancies between the misbehaviors of AP classes versus general education classes.

“When I did teach more CP/General Ed, you’re dealing with more of those behavioral issues, kids not paying attention, not turning in work, that stuff,” Miller told Spark. “Then in AP, you deal with more academic dishonesty.”

East Junior Emily, who chose not to provide a last name, told Spark that she sees disrespect at school on a daily basis.

“I don’t think too much of [the disrespect] just because it has become so normal,” Emily told Spark It’s awful that it has become a normal thing, but I always try to react with positivity instead of adding to the negative.” West Main Campus school resource officer Jeff Newman from the West Chester Police Department said that he sees more fights and disrespect at West Freshman when compared to West Main Campus. “You still have [disruptions and disrespect], but it’s just that maturity that kids go through [between freshman and sophomore year] that causes those problems to not be as prevalent once you get over to main campus,” Newman told Spark.

This is supported by an Ohio Data survey that said 29.0% of 9th graders and 21.6% of 10th graders reported being in one or more physical fights in Ohio in 2019, compared to 13.0% of 11th graders and 10.6% of 12th graders.

Experts like psychologist Lora LeMay point to numerous factors as to why adolescents act out in public and at school to the point of physical altercations, including but not limited to: normal brain changes, home environment, social media, peer pressure, and high stress.

The brain does not fully develop until around the age of 25 according to LeMay, meaning that the decision making part of the brain, known as the frontal lobe, is not fully developed in adolescence. LeMay said that this explains the likelihood of risky behavior and decision making in teens and young adults.

Another factor that contributes heavily to adolescent behavior is home life, according to Pediatrician Ronna Schneider PHD.

“If [parents] show any stress in the home, which it’s hard not to show that you are under stress, and if the child senses that all the time, there is a great chance that they could have some sort of behavioral issues like acting out, trying to gain attention, and then this can also bleed over to school, daycare, and other environments,” Schneider told Spark.

Both LeMay and Schneider said that social media, a newer form of external pressure on youth, inflames conflict between adolescents.

“[With social media] we can hide behind a veil, and that makes us a bit more brave when it comes to how we interact. We may say things [on social media] that we wouldn’t say to somebody face to face, and that can cause its own problems,” said LeMay.

As a teen, Emily agrees with this statement.

“Through social media,” said Emily, “you can’t tell someone’s tone of voice, body language, or how they really feel about something because all you are seeing is blank words on a screen, so a lot of times things get taken the wrong way.”

Emily, an AP and Honors student, finds ways to manage her stress with a busy schedule, which can be a cause of outbursts in school and in public according to LeMay.

“[Teens] are managing themselves to the point of exhaustion because there are so many things that they are involved in,” said LeMay. “They have to try to get into college, they have to hold a job, they have to get a driver’s license, manage family life, and be in sports and all kinds of things.”

These various factors contribute to the way that teenagers can behave, including in ways that would be considered disruptive to a public space or a learning environment.

At East, Miller said that she doesn’t witness fights very often.

“I think that’s because most of the time [fights] happen either after school or around lunch, and I am not near the cafeteria during lunch, so I don’t physically see them,” said Miller. “The amount of fights that I have heard about though, I feel like have increased.”

This perceived increase in disruption and fighting among teens was also noted by LeMay.

“There has been an increase [in disruptions in schools] because, while I haven’t seen it personally in terms of being out in public, I did notice an uptick in schools, where there were a lot more issues in regards to not following rules or being disrespectful,” said LeMay.

West Freshman school resource officer Patrick Eilerman from the West Chester Police Department noticed a recent difference in youth misbehavior, rather than an increase in the amount of misbehavior.

“When I first started in the schools, I had more of what I would call criminal incidents, where kids are doing actual criminal things, to where now the incidents and things that I deal with are more of maturity issues,” Eilerman told Spark.

Similarly, according to Batdorf, youth altercations are not on a steady incline.

“I’d say it’s just an up and down roller coaster,” said Batdorf. “You can go months and months and months without having a confrontation involving juveniles, or you can go two days back-to-back, and there’ll be two different confrontations.”

This is supported by a survey done by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) that stated 22% of students in grades 9-12 reported being in a physical fight in 2019, a decrease from the 31% of U.S. students in fights in 2009.

Hamilton Juvenile court records also show an approximate 41% decrease in complaints about delinquencies and unruly behavior among youth from 2013 to 2023.

With some seeing an increase in outbursts among youth, and statistics showing otherwise, East Freshman school counselor Kira Murphy attributes this discrepancy to the visibility of youth disruptions through social media outlets.

“[Social media] can cause more conflict because there’s a lot more damage that can be done in a shorter period of time. If you get a disagreement with somebody, that person can then spread that like wildfire, whereas before, you might have told two or three people,” said Murphy. “Also, some of the functions of some of these social media platforms, like location sharing and things, provide too much information.”

East Assistant Principal Katrina Murray amounts a perceived increase in outbursts to a recent change in attitude towards adults.

“When I first started in education, respect was warranted by the position and the person being an adult. There’s more of a worldview now post-COVID, that just because you’re an adult doesn’t mean that you earn [teens’] respect,” Murray told Spark. “There’s more questioning of adults now in society in general, and that’s not always a bad thing.”

Lemay said that disruptions in public also have to do with a societal lack of empathy.

“There’s a lot more entitlement, ‘I’m out for myself, I have to do what’s best for me.’ There’s truth to that, but we also have to be a functioning member of society, and we have to have empathy,” said LeMay. “I don’t think empathy is as embedded in our society now as it used to be.”

Regardless of whether there are more youth disturbances in public than in the past, social media may bring more attention to these issues.

“Everybody that has seen those posts wants to put their two cents in. Not necessarily to be the one to instigate that fight, but they want to see it and video it, because then they want to be the ones that posted it, or they want to be the ones that said they saw and it just constantly festers and it builds,” said Eilerman. “Even after it happens, we still deal with it sometimes days, weeks and months down the road.”

With or without definitive changes in youth outbursts over the years, different organizations and people are looking for possible solutions to decrease these issues.

Some of these proposed solutions include: personal stress management from students, building relationships between youth and mentors, increased policies in schools, increased policies in public spaces, and more positive opportunities for youth.

“I usually make a list of what needs to get done and prioritize what needs done first,” said Emily. “I also set goals for school, but I have my own personal goals of things I want to get done in a day or in the school year.”

Miller cultivates relationships with her students to reduce their stress in the classroom.

“In class, I try to build relationships with [students] and let them all know that I’m available by checking in on kids when I can and looking out for everyone,” said Miller. “By sharing about myself with [students], I’m hoping to humanize me in a way where they realize they can come talk to me.”

Murray also said that East attempts to lessen the inflammation that social media brings to these situations by implementing a new phone policy.

“[Students] acknowledge [the benefit of reduced time on their phones], but they’re still adolescents, so sometimes they need help understanding how to stay mentally healthy and how to make good choices,” said Murray. “The policy changes are there to help kids.”

On the whole, West school resource officer Jeff Newman from the West Chester Police department and others who have experience with adolescents have an optimistic approach to looking at the future.

“I look at society and I kind of worry about things on occasion. Like, where are we going?” Newman told Spark. “The best example that I know things are going to be fine is when I come into [West] every day, and everybody just gets along. They have little silly disputes, but most of the time they are able to navigate through and it’s fine.”

By and large, the NUL continues to combat youth disturbances by providing teens with opportunities like summer jobs. On a daily basis, George tries to give opportunities to the youth around her by being a positive influence.

“I’m inevitably a mentor to my employees,” said George, “but I’ve got a ton of kids that are regulars and I try to plant good seeds in their heads to help guide them in the right direction.”

From Batdorf’s perspective, “teenagers will be teenagers,” and while they may take horseplay and disrespect too far, sometimes they are “caught up in the moment.

On the whole however, West school resource officer Jeff Newman from the West Chester Police department and others who have experience with adolescents have an optimistic approach to looking at the future.

“I look at society and I kind of worry about things on occasion. Like, where are we going?” Newman told Spark. “The best example that I know things are going to be fine is when I come into [West] every day, and everybody just gets along. They have little silly disputes, but most of the time they are able to navigate through and it’s fine.”